This interview first appeared in Development.

Juergen Knoblich is a senior scientist and deputy scientific director of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. We met Juergen at the 56th Annual Drosophila Research Conference, where we asked him about his work in this model system and, more recently, on human cerebral organoids, and about his thoughts on recent technological developments and the funding situation.

How did you first become interested in biology? Was there someone who inspired you?

How did you first become interested in biology? Was there someone who inspired you?

I was always very interested in chemistry, but at some point my chemistry teacher told me that there was not much more to be discovered in chemistry, and that the new trend was to study biochemistry – which is what I did at university. It was really during my master’s thesis research that I became interested in genetics, and I got my training as a scientist during my PhD in the lab of Christian Lehner. He essentially taught me everything that I know about flies.

The Drosophila neuroblast has been the focus of your research for many years. Why did you choose this system?

I started my Drosophila career looking at cell cycle progression. As a PhD student I worked on cyclins and the transcriptional regulation of cell cycle exit. The logical next step for me was to look at the cell biology of mitosis itself. It so happened that my postdoc lab, the lab of Yuh Nung Jan at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), had just discovered the phenomenon of asymmetric cell division, which I then studied, mostly in the peripheral nervous system. The honest reason why I shifted to neuroblasts was that it allowed me to connect my cell biological research with something that is of very great medical relevance, i.e. stem cell biology. It is a fantastic cell biological system and you learn things from it that you can use and translate into higher organisms.

How do you feel that Drosophila research has changed over the course of your career?

Drosophila research over the past 10, 15 years has changed dramatically. If I had, as a PhD student, the technological tools available in flies now, I would have been the happiest person on Earth! Things are so much faster now. It started with the sequencing of the fly genome, which changed things completely. And now we have CRISPR-Cas, which is another revolution.

What is also very good about Drosophila as a model system is that there are a lot of people in the community who are fascinated by technology. They generate these absolutely fantastic collections, the latest being the MiMIC collection (http://flypush.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu/pscreen/index.php), that are available to the entire fly community and speed up our research so much.

Do you think that Drosophila as a genetic model system is being threatened by other model systems catching up with genomic tools?

I don’t think so. My lab uses not only Drosophila, but also mouse and human systems. So I honestly think that it is not just the technology that is better in Drosophila. There is a fundamental design difference between Drosophila and vertebrates. The enormous optimization of Drosophila development has eliminated many redundancies in the genome, and that comes in very handy for a geneticist. So when you make a certain mutation in Drosophila you typically get a very clear answer, and that is not usually the case in the mouse.

What is a threat to Drosophila research is that the interest of funding organizations and young scientists is starting to shift. Funding organizations are much more interested in direct medical translation. This is reflected in the interest of students. Drosophila as a system needs to switch to more disease-oriented research, and a lot

of groups are actually doing this. I think this enormous trend towards application is the real threat to Drosophila research. But it will survive.

Drosophila is famous as a genetic model, but you have been quite involved in RNAi screening efforts in this organism. What do you think is the relationship between knockout versus knockdown approaches, especially in the context of the recent developments in genome technology?

My lab makes extensive use of the genome-wide RNAi collection at the Vienna Drosophila Research Centre (VDRC). The collection was originally made by Barry Dickson and it is an absolutely invaluable resource for my lab. However, in some of the recent VDRC board meetings we discussed whether we have to prepare ourselves to stop maintaining this resource. Personally, I do not think RNAi will be replaced by CRISPR, and the reason for this is that RNAi is very versatile. You can make tissue-specific knockdowns, you can control them over time, you can make RNAi lines that have different knockdown levels, and they are a very successful tool to perform genome-wide screens.

CRISPR is a very interesting phenomenon. The technology is less than two years old and there has never been, to my knowledge, a technology that has so quickly transformed the entire field of genetics. It has effectively replaced other techniques to generate gene knockouts in flies, which were always difficult to use. In Drosophila, CRISPR is a great technology to generate stable loss-of-function point mutations, or for making insertions and tagging genes. But it cannot generate genome-wide loss-of-function resources that have the same versatility as the RNAi collection. Genome-wide loss-of-function screens using CRISPR-Cas will be possible at some point but will have their own problems, namely the fact that you do not have complete control over all the mutations that you make. So I think CRISPR and RNAi are complementary

techniques.

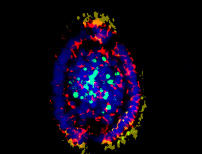

More recently, your lab has been making important contributions to the field of organogenesis, generating cerebral organoids in vitro. This is a shift away from the core focus of what your lab has been doing for many years…

It is quite an adventure for a Drosophila lab to all of a sudden work on human genetics, but I have a lot of fun trying out new things. We actually started shifting to the mouse a few years ago, and my lab now has almost five to six years of research experience in mouse brain development. The work of my lab is very much driven by the interest of the postdocs, and I typically develop projects with them, rather than telling them what to do. The organoid system was the project of Madeline Lancaster, who joined my lab as a postdoc initially to work on two-dimensional culture in mouse. We both then decided that it might actually be a really good idea to shift to humans, and to a three-dimensional culture. But she should take all the credit for the actual experimental protocol.

There was also a specific scientific question behind this project. As a postdoc I characterized a gene in Drosophila called inscuteable. Inscuteable is a molecular switch for spindle orientation. In mouse, changing the orientation of the mitotic spindle can change the number of neurons that are generated in the cortex, and a number of recent findings make inscuteable a really good candidate for the cortical enlargement you see as you go from the mouse to human. The one critical experiment that is missing is to

make a human inscuteable mutant. That was for me the real reason for developing this organoid system, and I hope that we will have this mutant very soon.

The cerebral organoids have a range of potential applications, from trying to understand how the brain develops at a more basic level to model human disease. Where would you like your lab to go next?

The core interest of my lab is lineage specification in stem cells. Recent findings have shown that there is a very strong difference in the cortical lineage between rodents and primates. Understanding this lineage change in evolution is one of the key questions that fascinate me, and I would like to address this question in my lab. However, modelling disease in organoids is not something that I want to neglect, and we have started to set up a translational research unit. But this is not going to be the core interest of my lab.

The cerebral organoids, often called minibrains, attracted a lot of media attention.What was your experience interacting with the press?

I should first say that the term ‘minibrains’ was not invented by us, but we were not surprised that they gained this name!

Nothing I did before ever generated such a high degree of media attention. I was quite well-prepared for it, and the press conference that was organized by Nature helped a lot in thinking about what the message was that I wanted to get across and how to best do that. I think that preparation for this kind of discussions is very important. Talking to the high-level news channels (such as the BBC or CNN) is very easy. It becomes more difficult when the tabloid press gets interested, but by taking the journalists seriously, and by preparing how to get the core of our message across, it can also work. Overall, it was a very good experience, and the press coverage was generally very positive. Everyone realized the enormous potential of what we did, and we addressed well the understandable concerns regarding what could be done with this system.

So you would encourage other scientists to interact with journalists?

I should say that for the organoids I had no choice! But in general, yes. Our research is funded by the public, and the public has a right to know what we are doing and why we are doing it. It is absolutely essential if we want to continue to be funded. This of course means going to the media. It also means accepting the rules of the media, and accepting that they have a different understanding of what is true or is not true. Conversely, we should also have a certain level of tolerance towards our colleagues when they explain things to the media or the lay public and deliberately use less accurate language.

How do you feel about the funding situation in Europe at the moment, particularly with the recent threat to the European Research Council (ERC) budget? Do we have reasons to worry?

Yes, I do think we have reasons to worry. For a long time there was a dogma that, even in times of reduced financial prosperity, the one thing that would not be touched were the long-term future investments, such as science and education. All of a sudden that changed, and I do not really understand why. The recent threat to the ERC project is, in my view, nothing less than a scandal. The ERC is one of the success stories of Europe; for once something in which the European Union has become a role model for other funding organizations. It has united European sciences. To cut the budget of this organization in favour of short-term investments is the wrong decision. Although I think the ERC will survive, any minor cut threatens the whole system, given the very low acceptance rate for ERC grants. There is no final decision on this yet, and I still hope the European Union will reconsider its decision.

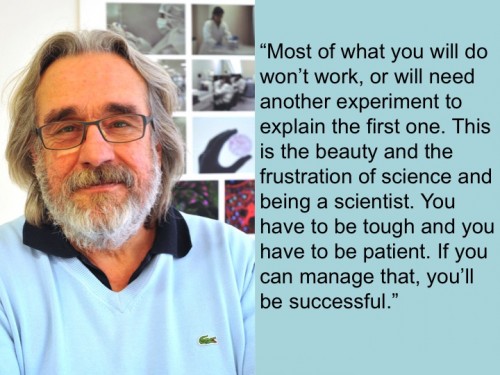

In this context of funding difficulties, what is your advice for young scientists?

I think what is happening at the moment is a transient phase, and as such we must distinguish between those whowant to go into science and those who are currently young scientists. Science funding, particularly for the biological sciences, grew strongly for a long time, but we have now reached a point where funding rates are constant, or even going down. There are a number of reasons for this. One of the reasons is that you cannot grow forever. The other is that biological sciences have made all sorts of promises, such as cures for a variety of diseases. At some point the public got impatient and said “now really deliver those cures”. This is why there is a strong shift towards translational research at the moment. This is, I think, a bit short-sighted, as we all know that the great discoveries in science do not come from a direct targeted discovery, but are to some degree serendipitous.

When you ask me what my advice is to young scientists, whether they should go into science, I think yes, by all means. They should pick the area by their interests, and not by the funding situation. My feeling is that we are undergoing a shrinking process, but this is a transient period. Indeed,when I started my PhD the situation was very similar. There was even a whole department dedicated to biologists at the Stuttgart unemployment office, because, among the natural scientists, biologists were the ones with the highest unemployment rate. This changed dramatically afterwards. On the other hand, if you ask me about the advice to give to people who are about to start their own lab, then it is tough at the moment and one really has to be very dedicated to being a scientist. But most of the people I know who really wanted to become a scientist succeeded in the end.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

In recent years there has been a growing interest in so-called stem cell ‘tourism’ – where a person (often companied by their carer/family) travels to another country for a purported stem cell treatment that is not available in their home country. Many advertised treatments are clinically unproven, with little or no evidence for their safety and efficacy in specific conditions.

In recent years there has been a growing interest in so-called stem cell ‘tourism’ – where a person (often companied by their carer/family) travels to another country for a purported stem cell treatment that is not available in their home country. Many advertised treatments are clinically unproven, with little or no evidence for their safety and efficacy in specific conditions.Professor Graziella Pellegrini is one of the principal scientists on the ground breaking, corneal repair system Holoclar®. Working throughout Italy over the past 27 years she is now based at the Centre for Regenerative Medicine “Stefano Ferrari” at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia.We spoke to Graziella about developing Holoclar, what it means for regenerative medicine in Europe, and what’s next.

We spoke to Michele De Luca,director of the Centre for Regenerative Medicine “Stefano Ferrari” at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, about his work, the importance of collaboration, and his aspirations. He also shares some great advice for scientists starting out.

We spoke to Michele De Luca,director of the Centre for Regenerative Medicine “Stefano Ferrari” at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, about his work, the importance of collaboration, and his aspirations. He also shares some great advice for scientists starting out. The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has launched a new website to help patients and their families make informed decisions about stem cell treatments, clinics and their health.

The International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has launched a new website to help patients and their families make informed decisions about stem cell treatments, clinics and their health. Researchers at the Hubrecht Institute and Utrecht University have developed a revolutionary and effective way of introducing molecular tools into cells. According to Dr. Niels Geijsen, who headed the research team, this discovery brings us one step closer to treating genetic diseases:

Researchers at the Hubrecht Institute and Utrecht University have developed a revolutionary and effective way of introducing molecular tools into cells. According to Dr. Niels Geijsen, who headed the research team, this discovery brings us one step closer to treating genetic diseases: There’s lots of new information in our fact sheet on stem cells and spinal cord injuries, updated this month.

There’s lots of new information in our fact sheet on stem cells and spinal cord injuries, updated this month. Un outil d’enseignement flexible qui introduit la recherche sur les cellules souches au moyen d’activités créatives en groupes et de discussions. Inclut des cartes d’activités imagées, des fiches de travail simples, des modèles de posters et un guide d’activités avec de nombreuses suggestions sur la façon d’utiliser le matériel.

Un outil d’enseignement flexible qui introduit la recherche sur les cellules souches au moyen d’activités créatives en groupes et de discussions. Inclut des cartes d’activités imagées, des fiches de travail simples, des modèles de posters et un guide d’activités avec de nombreuses suggestions sur la façon d’utiliser le matériel.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(5 votes)

(5 votes)

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series  (9 votes)

(9 votes)

Sesamoid bones are small, flat bones that are embedded within tendons. To date, it has been thought that these bones develop within tendons in response to mechanical signals, but now (on p.

Sesamoid bones are small, flat bones that are embedded within tendons. To date, it has been thought that these bones develop within tendons in response to mechanical signals, but now (on p.  A balanced network of excitatory and inhibitory synapses is required for correct brain function, and any perturbations to this balance can give rise to neurological and psychiatric disorders. It has been shown previously that FGF22 and FGF7 promote excitatory or inhibitory synapse formation, respectively, in the hippocampus, but how do these ligands mediate their synaptogenic effects? Here, Hisashi Umemori and co-workers use various FGF receptor knockout mice to address this question (p.

A balanced network of excitatory and inhibitory synapses is required for correct brain function, and any perturbations to this balance can give rise to neurological and psychiatric disorders. It has been shown previously that FGF22 and FGF7 promote excitatory or inhibitory synapse formation, respectively, in the hippocampus, but how do these ligands mediate their synaptogenic effects? Here, Hisashi Umemori and co-workers use various FGF receptor knockout mice to address this question (p.  Human embryos are particularly susceptible to chromosome instability (CIN) and errors in chromosome segregation, but the molecular mechanisms that regulate and sense CIN in mammalian embryos are unclear. Here, on p.

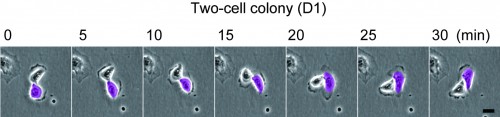

Human embryos are particularly susceptible to chromosome instability (CIN) and errors in chromosome segregation, but the molecular mechanisms that regulate and sense CIN in mammalian embryos are unclear. Here, on p.  During development, epithelial tubes often need to grow while still maintaining their barrier properties. How can cells divide without disrupting the integrity of the tubular epithelium? On p.

During development, epithelial tubes often need to grow while still maintaining their barrier properties. How can cells divide without disrupting the integrity of the tubular epithelium? On p.  The segmentation clock, which controls the periodic formation of somites along the vertebrate body axis, involves the oscillating expression of clock genes in presomitic mesoderm (PSM) cells. Oscillations are synchronised between cells, giving rise to a sweeping wave of gene expression throughout the PSM. This cyclic wave of gene expression is known to slow as it moves anteriorly, but the causes and implications of this slowing have remained unclear. Here, Sharon Amacher and co-workers investigate segmentation clock dynamics in zebrafish embryos (p.

The segmentation clock, which controls the periodic formation of somites along the vertebrate body axis, involves the oscillating expression of clock genes in presomitic mesoderm (PSM) cells. Oscillations are synchronised between cells, giving rise to a sweeping wave of gene expression throughout the PSM. This cyclic wave of gene expression is known to slow as it moves anteriorly, but the causes and implications of this slowing have remained unclear. Here, Sharon Amacher and co-workers investigate segmentation clock dynamics in zebrafish embryos (p.  Juergen Knoblich is a senior scientist and deputy scientific director of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. We met Juergen at the 56th Annual Drosophila Research Conference, where we asked him about his work in this model system and, more recently, on human cerebral organoids, and about his thoughts on recent technological developments and the funding situation.

Juergen Knoblich is a senior scientist and deputy scientific director of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. We met Juergen at the 56th Annual Drosophila Research Conference, where we asked him about his work in this model system and, more recently, on human cerebral organoids, and about his thoughts on recent technological developments and the funding situation. In February 2015, scientists gathered for the Keystone Hematopoiesis meeting, which was held at the scenic Keystone Resort in Colorado, USA. During the exciting program, field leaders and new investigators presented discoveries that spanned developmental and adult hematopoiesis within both physiologic and pathologic contexts. See the Meeting Review on p.

In February 2015, scientists gathered for the Keystone Hematopoiesis meeting, which was held at the scenic Keystone Resort in Colorado, USA. During the exciting program, field leaders and new investigators presented discoveries that spanned developmental and adult hematopoiesis within both physiologic and pathologic contexts. See the Meeting Review on p.  The segmented vertebral column comprises a repeat series of vertebrae, each consisting of the vertebral body and the vertebral arches. Despite being a defining feature of vertebrates, much remains to be understood about vertebral development and evolution. Particular controversy surrounds whether vertebral structures are homologous across vertebrates, how somite and vertebral patterning are connected, and the developmental origin of vertebral bone-mineralizing cells. Here, Roger Keynes and colleagues consider these issues. See the Review on p.

The segmented vertebral column comprises a repeat series of vertebrae, each consisting of the vertebral body and the vertebral arches. Despite being a defining feature of vertebrates, much remains to be understood about vertebral development and evolution. Particular controversy surrounds whether vertebral structures are homologous across vertebrates, how somite and vertebral patterning are connected, and the developmental origin of vertebral bone-mineralizing cells. Here, Roger Keynes and colleagues consider these issues. See the Review on p.