In Development this week (Vol. 141, Issue 24)

Posted by Seema Grewal, on 2 December 2014

Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

Assessing the evolutionary origin of neural progenitors

The nervous system of bilaterians arises from a small pool of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) that expressesSoxB genes, a family of transcription factors crucial for neurogenesis. The existence of NPCs has thus far been described in diverse species of Bilateria but not in its sister group, the Cnidaria. Hence, the evolutionary origin of NPCs remains obscure. Gemma Richards and Fabian Rentzsch (p. 4681) now investigate the cellular origin of neural cells in Nematostella vectensis, a sea anemone belonging to the Cnidaria group. They find that NvSoxB(2), a gene closely related to the bilaterianSoxB genes, is expressed in a mitotically active cell population that gives rise to three neuronal classes found in Nematostella. Further, using knockdown experiments, the authors showed that NvSoxB(2) is required for proper neural development. This study uncovers the existence of a dedicated NPC population for the first time outside bilaterians and identifies SoxB genes as ancient regulators of neurogenesis. Although many questions about the precise role of NvSoxB(2) in Nematostella remain to be answered, these results provide a fundamental insight into evolutionarily conserved core aspects of neural development.

The nervous system of bilaterians arises from a small pool of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) that expressesSoxB genes, a family of transcription factors crucial for neurogenesis. The existence of NPCs has thus far been described in diverse species of Bilateria but not in its sister group, the Cnidaria. Hence, the evolutionary origin of NPCs remains obscure. Gemma Richards and Fabian Rentzsch (p. 4681) now investigate the cellular origin of neural cells in Nematostella vectensis, a sea anemone belonging to the Cnidaria group. They find that NvSoxB(2), a gene closely related to the bilaterianSoxB genes, is expressed in a mitotically active cell population that gives rise to three neuronal classes found in Nematostella. Further, using knockdown experiments, the authors showed that NvSoxB(2) is required for proper neural development. This study uncovers the existence of a dedicated NPC population for the first time outside bilaterians and identifies SoxB genes as ancient regulators of neurogenesis. Although many questions about the precise role of NvSoxB(2) in Nematostella remain to be answered, these results provide a fundamental insight into evolutionarily conserved core aspects of neural development.A-SIRT-aining how metabolism regulates adult neurogenesis

Continuous neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus is achieved by a tightly regulated balance between adult neural stem cell (aNSCs) self-renewal and differentiation. aNSC self-renewal is maintained by the action of ‘stemness’ genes, including Notch. Conversely, aNSC differentiation involves both the inactivation of the ‘stemness’ genes and activation of pro-neural genes. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is regulated by intrinsic stimuli such as epigenetic modifications, as well as extrinsic inputs such as exercise, diet or hypoxia, which ultimately cause metabolic stress. However, the molecular mechanisms linking metabolic changes to the epigenetic control of aNSCs remain unclear. Using genetic ablation and pharmacological manipulation in mouse (p. 4697), Mu-ming Poo and co-workers show that SIRT1, a NAD+ dependent histone deacetylase and known metabolic sensor, inhibits aNSC self-renewal both in vivo and in vitro by suppressing Notch signalling in a cell-autonomous manner. Furthermore, the authors show that SIRT1 mediates the effect of metabolic stress induced by glucose restriction on aNSCs proliferation in vitro. Altogether, these results uncover a molecular mediator of the metabolic regulation of adult neurogenesis, opening the door to a better understanding and potential manipulation of adult neurogenesis.

Continuous neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus is achieved by a tightly regulated balance between adult neural stem cell (aNSCs) self-renewal and differentiation. aNSC self-renewal is maintained by the action of ‘stemness’ genes, including Notch. Conversely, aNSC differentiation involves both the inactivation of the ‘stemness’ genes and activation of pro-neural genes. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is regulated by intrinsic stimuli such as epigenetic modifications, as well as extrinsic inputs such as exercise, diet or hypoxia, which ultimately cause metabolic stress. However, the molecular mechanisms linking metabolic changes to the epigenetic control of aNSCs remain unclear. Using genetic ablation and pharmacological manipulation in mouse (p. 4697), Mu-ming Poo and co-workers show that SIRT1, a NAD+ dependent histone deacetylase and known metabolic sensor, inhibits aNSC self-renewal both in vivo and in vitro by suppressing Notch signalling in a cell-autonomous manner. Furthermore, the authors show that SIRT1 mediates the effect of metabolic stress induced by glucose restriction on aNSCs proliferation in vitro. Altogether, these results uncover a molecular mediator of the metabolic regulation of adult neurogenesis, opening the door to a better understanding and potential manipulation of adult neurogenesis.

REVolutions in leaf development: from origin to senescence

In both plants and animals, cellular senescence is not only an age-related process, but can also contribute to developmental programs. In plants, senescence can occur with age and in response to suboptimal growing conditions to reallocate nutrients from the leaves to the developing parts of the plant, particularly to maturing seeds. However, the interplay between age- or environmentally induced senescence and developmental programs is still unclear. Using a ChIP-Seq approach in Arabidopsis (p. 4772), the groups of Stephan Wenkel and Ulrike Zentgraf demonstrate that REVOLUTA (REV), a transcription factor well known to establish polarity in the developing plant, directly regulates the expression of WRKY53, a master regulator of age-induced leaf senescence. Furthermore, the authors show that mutations in REV delay the onset of leaf senescence and that REV functions as a redox sensor that modulates the expression of WRKY53 in response to oxidative stress, a known trigger of senescence. Altogether, this study uncovers a coupling between developmental programs and senescence transcriptional networks in the leaf. This opens the possibility that, conversely, senescence-related tissue degradation might also contribute to early leaf development.

In both plants and animals, cellular senescence is not only an age-related process, but can also contribute to developmental programs. In plants, senescence can occur with age and in response to suboptimal growing conditions to reallocate nutrients from the leaves to the developing parts of the plant, particularly to maturing seeds. However, the interplay between age- or environmentally induced senescence and developmental programs is still unclear. Using a ChIP-Seq approach in Arabidopsis (p. 4772), the groups of Stephan Wenkel and Ulrike Zentgraf demonstrate that REVOLUTA (REV), a transcription factor well known to establish polarity in the developing plant, directly regulates the expression of WRKY53, a master regulator of age-induced leaf senescence. Furthermore, the authors show that mutations in REV delay the onset of leaf senescence and that REV functions as a redox sensor that modulates the expression of WRKY53 in response to oxidative stress, a known trigger of senescence. Altogether, this study uncovers a coupling between developmental programs and senescence transcriptional networks in the leaf. This opens the possibility that, conversely, senescence-related tissue degradation might also contribute to early leaf development.Taking the pulse of Notch signalling during somitogenesis

During development, somites form by periodic budding from the pre-somitic mesoderm (PSM), and give rise to the vertebral column and most of the muscles and skin. This process is driven by the pulsatile expression of ‘clock genes’, the expression of which is synchronized across the PSM. This synchronicity is regulated by the Notch pathway. Notch1 and its ligand Delta1 (Dll1) are reported to be expressed in a continuous gradient in the PSM and it is unclear how these static receptor and ligand profiles can drive and synchronise pulsatile gene expression. Through experiments in mouse and chick (p. 4806), Kim Dale and colleagues find that, in addition to their graded expression across the tissue, Notch1 and Dll1 mRNA and protein levels actually oscillate themselves, in a manner dependent on Notch and Wnt, respectively. Moreover, Notch1 and Dll1 waves are coordinated with the cyclical expression of Lfng, a known Notch target, and with the oscillating levels of the activated Notch intracellular domain, indicating a periodical activation of the Notch pathway. This study provides the first evidence of the pulsatile production of endogenous Notch and Delta at the protein level, and offers a potential mechanism by which cells synchronize to give rise to pulsatile waves across the PSM.

During development, somites form by periodic budding from the pre-somitic mesoderm (PSM), and give rise to the vertebral column and most of the muscles and skin. This process is driven by the pulsatile expression of ‘clock genes’, the expression of which is synchronized across the PSM. This synchronicity is regulated by the Notch pathway. Notch1 and its ligand Delta1 (Dll1) are reported to be expressed in a continuous gradient in the PSM and it is unclear how these static receptor and ligand profiles can drive and synchronise pulsatile gene expression. Through experiments in mouse and chick (p. 4806), Kim Dale and colleagues find that, in addition to their graded expression across the tissue, Notch1 and Dll1 mRNA and protein levels actually oscillate themselves, in a manner dependent on Notch and Wnt, respectively. Moreover, Notch1 and Dll1 waves are coordinated with the cyclical expression of Lfng, a known Notch target, and with the oscillating levels of the activated Notch intracellular domain, indicating a periodical activation of the Notch pathway. This study provides the first evidence of the pulsatile production of endogenous Notch and Delta at the protein level, and offers a potential mechanism by which cells synchronize to give rise to pulsatile waves across the PSM.

Sickie: ensuring healthy axonal growth

Building the elaborate neural networks required for brain function involves profound cytoskeleton remodelling during axonal growth and pathfinding. In particular, axonal growth is supported by the growth cone, a dynamic F-actin based structure, and regulated by ADF/Cofilin, an F-actin destabilising protein. Cofilin is activated by dephosphorylation by Slingshot (Ssh), and inhibited by LIMK-mediated phosphorylation. Activity of these regulators is in turn influenced by the small GTPase Rac, which acts via Pak to promote LIMK activity and inhibit Cofilin, but also via a Pak-independent, non-canonical pathway to promote Cofilin activity. However, the molecular mediators of the non-canonical pathway are currently unknown. Here (p. 4716), Takashi Abe and colleagues identify Sickie, a protein that can interact with both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons, as a regulator of axonal growth in the Drosophila mushroom body. By visualizing Cofilin phosphorylation and F-actin state in vivo, the authors show that Sickie participates in the non-canonical pathway, regulating Cofilin-mediated axonal growth in a Ssh-dependent manner. This study reveals an important new regulator of Cofilin and may provide insights into the molecular basis of the coordination between actin and microtubules during axonal growth.

Building the elaborate neural networks required for brain function involves profound cytoskeleton remodelling during axonal growth and pathfinding. In particular, axonal growth is supported by the growth cone, a dynamic F-actin based structure, and regulated by ADF/Cofilin, an F-actin destabilising protein. Cofilin is activated by dephosphorylation by Slingshot (Ssh), and inhibited by LIMK-mediated phosphorylation. Activity of these regulators is in turn influenced by the small GTPase Rac, which acts via Pak to promote LIMK activity and inhibit Cofilin, but also via a Pak-independent, non-canonical pathway to promote Cofilin activity. However, the molecular mediators of the non-canonical pathway are currently unknown. Here (p. 4716), Takashi Abe and colleagues identify Sickie, a protein that can interact with both the actin and microtubule cytoskeletons, as a regulator of axonal growth in the Drosophila mushroom body. By visualizing Cofilin phosphorylation and F-actin state in vivo, the authors show that Sickie participates in the non-canonical pathway, regulating Cofilin-mediated axonal growth in a Ssh-dependent manner. This study reveals an important new regulator of Cofilin and may provide insights into the molecular basis of the coordination between actin and microtubules during axonal growth.PLUS…

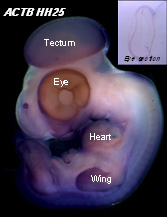

The developmental hourglass model: a predictor of the basic body plan?

![]() The ‘hourglass model’ suggests that embryos of different species diverge more at early and late stages of development, but are most conserved during a mid, phylotypic, period. Irie and Kuratani discuss the evidence for this model, and possible underlying mechanisms. See the Review on p. 4649

The ‘hourglass model’ suggests that embryos of different species diverge more at early and late stages of development, but are most conserved during a mid, phylotypic, period. Irie and Kuratani discuss the evidence for this model, and possible underlying mechanisms. See the Review on p. 4649

The analysis, roles and regulation of quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells

Quiescence has been proposed as a fundamental property of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), acting to protect them from functional exhaustion and cellular insults to enable lifelong hematopoietic cell production. Toshio Suda and colleagues review the current methods available to measure quiescence in HSCs and discuss the roles and regulation of HSC quiescence. See the Review on p. 4656

Quiescence has been proposed as a fundamental property of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), acting to protect them from functional exhaustion and cellular insults to enable lifelong hematopoietic cell production. Toshio Suda and colleagues review the current methods available to measure quiescence in HSCs and discuss the roles and regulation of HSC quiescence. See the Review on p. 4656

Transcription factors and effectors that regulate neuronal morphology

Transcription factors establish the tremendous diversity of cell types in the nervous system by regulating the expression of genes that give a cell its morphological and functional properties. Celine Santiago and Greg Bashaw highlight recent work that has elucidated the functional relationships between transcription factors and the downstream effectors through which they regulate neural connectivity in multiple model systems. See the Review on p. 4667

Transcription factors establish the tremendous diversity of cell types in the nervous system by regulating the expression of genes that give a cell its morphological and functional properties. Celine Santiago and Greg Bashaw highlight recent work that has elucidated the functional relationships between transcription factors and the downstream effectors through which they regulate neural connectivity in multiple model systems. See the Review on p. 4667

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(7 votes)

(7 votes)