A few months ago we ran a survey on the Node to ask how you used the site, and if you had any suggestions. First of all, a big thank-you to all of you who took the time to answer our questions. As promised, we held a random draw among the survey participants: the winner was Gregory Shanower and he has been sent some gifts from Development and the Node. Congratulations!

A few months ago we ran a survey on the Node to ask how you used the site, and if you had any suggestions. First of all, a big thank-you to all of you who took the time to answer our questions. As promised, we held a random draw among the survey participants: the winner was Gregory Shanower and he has been sent some gifts from Development and the Node. Congratulations!

So what did the survey tell us?

The complete report is 13 pages long. We’ll spare you that, but there were some recurring themes that we thought you might be interested in, so here is a short summary of the results – just to give you a brief idea of what we’ll be focusing on in the near future:

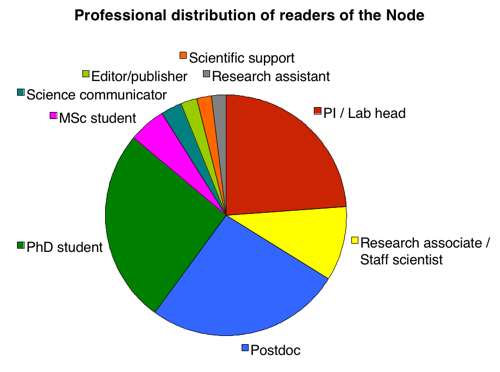

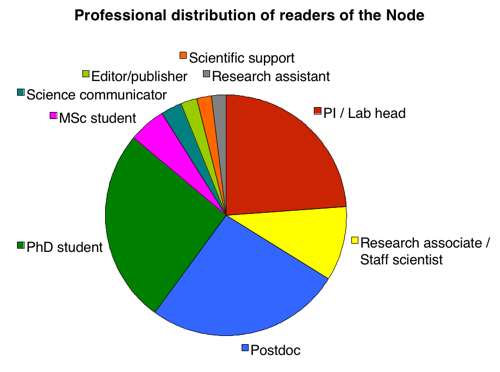

Who is reading the Node?

Let’s start by shattering a myth. One of the biggest misconceptions about the Node is that it’s “only for young people”. We hear this comment regularly but we now have the data to prove that it is not true. As the pie chart below shows, there is an equal distribution of PhD students, postdocs and PIs reading the Node. (Considering that in absolute numbers there are far more PhD students and postdocs than there are PIs, this means that, relatively speaking, the Node seems to be more popular among PIs than among younger researchers!)

Other facts about you, the Node’s readers:

* Almost 90% of the Node audience identifies as developmental biologists, but many also have interests in cell biology, genetics, stem cell research, or other areas of the life sciences.

* One in four Node readers has heard about the Node from a friend or colleague. Thank you for talking about us!

What are the most popular features on the Node?

Aside from the main content on the Node, the job postings and event listings are the most popular features. This is as good a place as any to remind everyone that you can add jobs and events if you have a Node account. You’ll receive posting instructions once your account is approved. Speaking of which…

Writing for the Node

About a third of the survey respondents has written posts or comments on the Node, posted job ads, or added events. Almost as many people indicated that they had not written anything on the Node, but would like to write something.

Of the people who had never posted on the Node, some said they didn’t have time, or that they were not confident about making their opinions public. Many others simply didn’t know what to write about, or didn’t know that they could, so we’ll be doing a bit more in the future to make it clear that anyone can post and we’ll try to set up a resource (perhaps an opt-in mailing list) to offer topics and ideas for Node posts for enthusiastic (current and future) Node contributors who suffer from writers block.

Keeping up with the Node

One of the most striking things that we found in the survey is that a lot of you are simply not able to keep up with everything on the Node, and more than half of you simply scroll through posts on the homepage. One immediate solution is that we’ll start doing monthly summary posts, highlighting some of the content from earlier that month. Here is the first one, for September 2011. We’ll also see if there is anything we can do in terms of layout and presentation, but that will be a more long-term plan.

Topics

Finally, we received a lot of great suggestions for features and for topics for future Node posts, and we’ll try to get as many of those on the site as we can. (Of course everything depends on people actually writing content, so it’s ultimately up to you.)

Several people made a suggestion that was quite straightforward and that we’ve already started in response to these suggestions: to do regular round-ups of upcoming deadlines for meetings, scholarships or grants. It’s hard to ensure such updates are complete, so if you see one of these posts and know of another deadline, feel free to post it yourself, or leave a comment on a previous deadline post. You don’t need an account to comment, and your email address will never be public.

If you have any questions about the survey we ran, or if you have some additional suggestions for the Node, feel free to leave a comment below.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(4 votes)

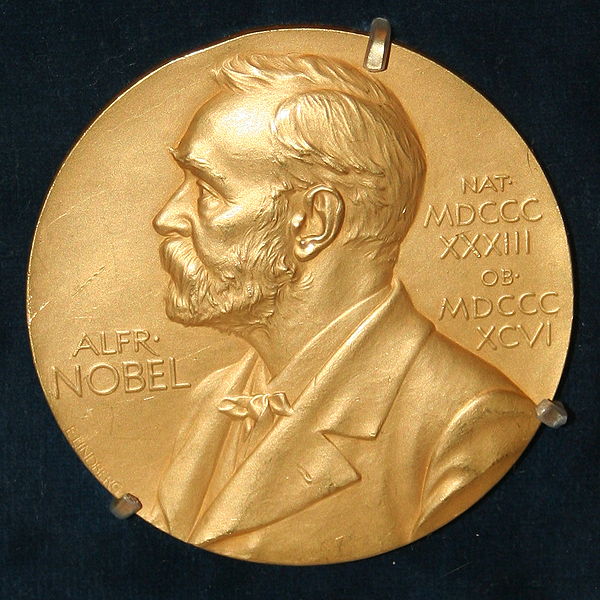

(4 votes) October 7 is

October 7 is  A few months ago we ran a

A few months ago we ran a

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

“At the end of the day, when people believe that a human embryo from the time of conception is worthy of all protection, you cannot argue against that. All I can argue is that we are in a situation where human embryos through IVF programmes are discarded, and isn’t it more ethically acceptable to use those discarded embryos to help save human lives in the future?” –

“At the end of the day, when people believe that a human embryo from the time of conception is worthy of all protection, you cannot argue against that. All I can argue is that we are in a situation where human embryos through IVF programmes are discarded, and isn’t it more ethically acceptable to use those discarded embryos to help save human lives in the future?” –  “We think of proteins and genes, but there are all also lipids and sugars, and we are ignoring them completely! Maybe the future could be to measure them, find out where they are and how they influence things. Chemistry could be the future.” –

“We think of proteins and genes, but there are all also lipids and sugars, and we are ignoring them completely! Maybe the future could be to measure them, find out where they are and how they influence things. Chemistry could be the future.” –