My lab works on developmental bioelectricity, studying how cells communicate via endogenous gradients of plasma membrane resting potential (Vmem) in order to coordinate their activity during pattern regulation (Levin, 2013; Levin, 2014b; Tseng and Levin, 2013). It is well-known that resting potential is an important regulatory parameter for individual cells’ proliferation, differentiation, and oncogenic potential (Blackiston et al., 2009; Sundelacruz et al., 2009). Voltage itself is an important “master control knob” because the same morphogenetic phenotype (e.g., inducing eye formation or metastatic conversion) can be induced by using sodium, potassium, chloride, or even proton flows to achieve a particular Vmem level. The chemical nature of the ion (and the genetic identity of the channel) often does not matter, as long as the voltage gradient is established correctly for a particular downstream outcome. In this Node post, I wanted to briefly mention a few of our recent studies which highlight an exciting new aspect of this field: long-range signaling via gap junctions.

Gap junctions (GJs) are electrical synapses – direct conduits for small molecules between cells, which can be used to form isoelectric compartments in vivo; they have numerous roles in normal development and disease (Levin, 2007; Sohl and Willecke, 2004; Wong et al., 2008). Most importantly, they are extremely versatile signaling elements (Palacios-Prado and Bukauskas, 2009; Pereda et al., 2013), because they both regulate cellular resting potential and are themselves voltage-gated. GJs are able to function as a kind of transistor, allowing voltage to control current flow. Because they are ideally-suited to process information in physiological cell networks, is no surprise that gap junctional communication is a key regulator of brain activity, developmental patterning, and carcinogenesis.

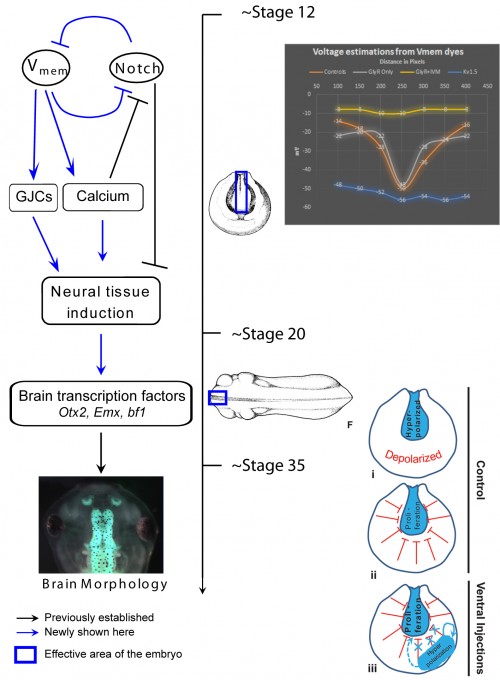

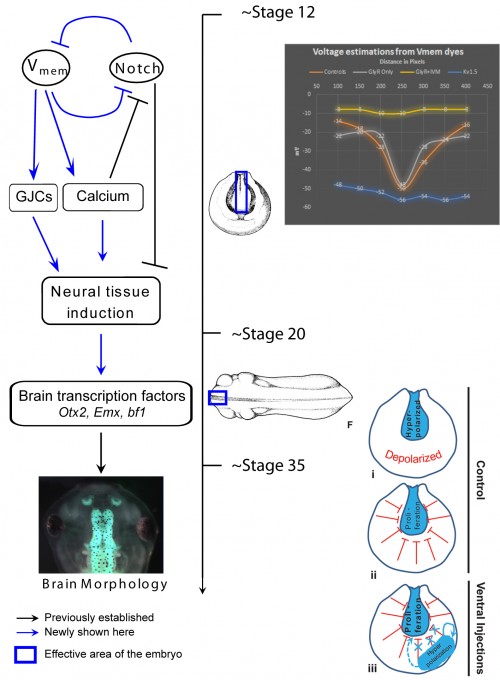

One of our recent studies investigated the role of endogenous bioelectric gradients in brain formation in the Xenopus lae vis embryo (Pai et al., 2015). Early frog embryos exhibit a characteristic hyperpolarization of cells lining the neural tube; disruption of this spatial gradient of the transmembrane potential (Vmem ), using misexpression of depolarizing channels, diminishes or eliminates the expression of early brain markers, and causes anatomical mispatterning of the brain. Conversely, forced establishment of the brain-specific voltage pattern (using expression of select ion channels) was able to rescue brain defects induced by mutant Notch protein (a potent regulator of neurogenesis), and even induce ectopic brain tissue in posterior regions of the tadpole.

vis embryo (Pai et al., 2015). Early frog embryos exhibit a characteristic hyperpolarization of cells lining the neural tube; disruption of this spatial gradient of the transmembrane potential (Vmem ), using misexpression of depolarizing channels, diminishes or eliminates the expression of early brain markers, and causes anatomical mispatterning of the brain. Conversely, forced establishment of the brain-specific voltage pattern (using expression of select ion channels) was able to rescue brain defects induced by mutant Notch protein (a potent regulator of neurogenesis), and even induce ectopic brain tissue in posterior regions of the tadpole.

In addition to cell-autonomous effects, we showed that hyperpolarization of transmembrane potential (Vmem ) in ventral cells, well-outside the brain, induced upregulation of neural cell proliferation. These long-range effects were mediated by gap junctional communication, and another recent paper extended such long-range regulation of cell division to similar non-local control of apoptosis (Pai, 2015). We suggested a model in which brain cells coordinate growth and sculpting decisions with the remaining tissues (to determine appropriate location, size, and boundaries of the nascent brain) via electrical signals mediated by GJ paths.

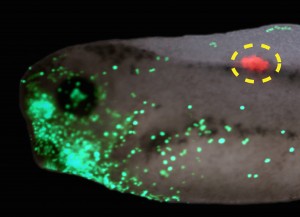

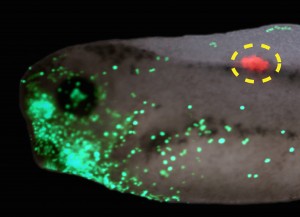

Interestingly, a similar story was found for tumorigenesis in Xenopus (Chernet et al., 2014). mRNA encoding mutant KRAS induces tumors in a zebrafish cancer model (Le et al., 2007). We showed that the same thing happens in Xenopus (complete with induced angiogenesis, overproliferation, expression of tumor markers, and immune response); remarkably, a specific bioelectric state of cells at a considerable distance (on the other side of the body) can suppress tumor formation, despite strong expression of the oncogene. The effect is mediated by butyrate signaling (Chernet and Levin, 2014), which links voltage regulation to chromatin modification, and – GJs. These data are part of a growing body of evidence (Bizzarri and Cucina, 2014; Chernet and Levin, 2013; Soto and Sonnenschein, 2011; Tarin, 2011) highlighting aspects of cancer as a “disease of geometry” – a disorder of patterning cues and cell:cell communication that normally harnesses cell activity towards specific morphogenetic goals and away from tumorigenesis.

Interestingly, a similar story was found for tumorigenesis in Xenopus (Chernet et al., 2014). mRNA encoding mutant KRAS induces tumors in a zebrafish cancer model (Le et al., 2007). We showed that the same thing happens in Xenopus (complete with induced angiogenesis, overproliferation, expression of tumor markers, and immune response); remarkably, a specific bioelectric state of cells at a considerable distance (on the other side of the body) can suppress tumor formation, despite strong expression of the oncogene. The effect is mediated by butyrate signaling (Chernet and Levin, 2014), which links voltage regulation to chromatin modification, and – GJs. These data are part of a growing body of evidence (Bizzarri and Cucina, 2014; Chernet and Levin, 2013; Soto and Sonnenschein, 2011; Tarin, 2011) highlighting aspects of cancer as a “disease of geometry” – a disorder of patterning cues and cell:cell communication that normally harnesses cell activity towards specific morphogenetic goals and away from tumorigenesis.

It appears that in diverse contexts, such as embryonic establishment of pattern and tumor suppression, GJs link bioelectric and biochemical pathways to regulate events at considerable distance. Thus, future work must focus not only on ever-more detailed dissection of biophysical signaling events within single cells, but also address group dynamics and large-scale emergent properties of physiological networks linked by electrical synapses (Donnell et al., 2009; Levin, 2014a; Saraga et al., 2006; Schiffmann, 2008; Steyn-Ross et al., 2007). Multicellular models of GJ signaling will surely contribute to the understanding of patterning and deviations from normal growth and form.

References

Bizzarri, M. and Cucina, A. (2014). Tumor and the microenvironment: a chance to reframe the paradigm of carcinogenesis? Biomed Res Int 2014, 934038, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25013812

Blackiston, D. J., McLaughlin, K. A. and Levin, M. (2009). Bioelectric controls of cell proliferation: ion channels, membrane voltage and the cell cycle. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex 8, 3519-3528, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19823012

Chernet, B. and Levin, M. (2013). Endogenous Voltage Potentials and the Microenvironment: Bioelectric Signals that Reveal, Induce and Normalize Cancer. J Clin Exp Oncol Suppl 1, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25525610

Chernet, B., and Levin, M., (2014), “Transmembrane voltage potential of somatic cells controls oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis at long-range”, Oncotarget, 5(10): 3287-3306

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24830454

Chernet, B. T., Fields, C. and Levin, M. (2014). Long-range gap junctional signaling controls oncogene-mediated tumorigenesis in Xenopus laevis embryos. Front Physiol 5, 519, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25646081

Donnell, P., Baigent, S. A. and Banaji, M. (2009). Monotone dynamics of two cells dynamically coupled by a voltage-dependent gap junction. Journal of theoretical biology 261, 120-125, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19627994

Le, X., Langenau, D. M., Keefe, M. D., Kutok, J. L., Neuberg, D. S. and Zon, L. I. (2007). Heat shock-inducible Cre/Lox approaches to induce diverse types of tumors and hyperplasia in transgenic zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 9410-9415, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17517602

Levin, M. (2007). Gap junctional communication in morphogenesis. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 94, 186-206, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17481700

Levin, M. (2013). Reprogramming cells and tissue patterning via bioelectrical pathways: molecular mechanisms and biomedical opportunities. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine 5, 657-676, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23897652

Levin, M. (2014a). Endogenous bioelectrical networks store non-genetic patterning information during development and regeneration. The Journal of Physiology 592, 2295-2305, http://jp.physoc.org/content/592/11/2295.abstract

Levin, M. (2014b). Molecular bioelectricity: how endogenous voltage potentials control cell behavior and instruct pattern regulation in vivo. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3835-3850, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25425556

Pai, V. P., Lemire J. M., Chen Y., Lin G., and Levin M. (2015). Local and long-range endogenous resting potential gradients antagonistically regulate apoptosis and proliferation in the embryonic CNS. Int. J. Dev. Biol., in press

Pai, V. P., Lemire, J. M., Pare, J. F., Lin, G., Chen, Y., & Levin, M. (2015). Endogenous Gradients of Resting Potential Instructively Pattern Embryonic Neural Tissue via Notch Signaling and Regulation of Proliferation Journal of Neuroscience, 35 (10), 4366-4385 DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1877-14.2015

Palacios-Prado, N. and Bukauskas, F. F. (2009). Heterotypic gap junction channels as voltage-sensitive valves for intercellular signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 14855-14860, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19706392

Pereda, A. E., Curti, S., Hoge, G., Cachope, R., Flores, C. E. and Rash, J. E. (2013). Gap junction-mediated electrical transmission: regulatory mechanisms and plasticity. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1828, 134-146, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22659675

Saraga, F., Ng, L. and Skinner, F. K. (2006). Distal gap junctions and active dendrites can tune network dynamics. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 1669-1682, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16339003

Schiffmann, Y. (2008). The Turing-Child energy field as a driver of early mammalian development. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 98, 107-117, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18680762

Sohl, G. and Willecke, K. (2004). Gap junctions and the connexin protein family. Cardiovasc Res 62, 228-232, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15094343

Soto, A. M. and Sonnenschein, C. (2011). The tissue organization field theory of cancer: a testable replacement for the somatic mutation theory. Bioessays 33, 332-340, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21503935

Steyn-Ross, M. L., Steyn-Ross, D. A., Wilson, M. T. and Sleigh, J. W. (2007). Gap junctions mediate large-scale Turing structures in a mean-field cortex driven by subcortical noise. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys 76, 011916, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17677503

Sundelacruz, S., Levin, M. and Kaplan, D. L. (2009). Role of membrane potential in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. Stem cell reviews and reports 5, 231-246, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=19562527

Tarin, D. (2011). Cell and tissue interactions in carcinogenesis and metastasis and their clinical significance. Semin Cancer Biol 21, 72-82, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21147229

Tseng, A. and Levin, M. (2013). Cracking the bioelectric code: Probing endogenous ionic controls of pattern formation. Communicative & Integrative Biology 6, 1-8, http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cib/article/22595/

Wong, R. C., Pera, M. F. and Pebay, A. (2008). Role of gap junctions in embryonic and somatic stem cells. Stem Cell Rev 4, 283-292, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18704771

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)