47th Meeting of the Japanese Society of Developmental Biologists, Nagoya

Posted by Juan Pascual-Anaya, on 19 June 2014

The heat started to increase in Japan, as the rainy season approached and with it the high levels of temperature and humidity. But this was not an obstacle for scientists from all over Japan (and also some scientists from abroad) to meet in the great and beautiful city of Nagoya, in Aichi prefecture. Here took place the 47th Meeting of the Japanese Society of Developmental Biologists (27th-30th May 2014). The meeting was greatly organized by Masahiko Hibi-sensei, a professor in the University of Nagoya, who, as it happens, was a previous PI in my current institute, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology.

The meeting embraced developmental biologists from a high variety of fields, and thus it was not that small albeit being a national meeting. So, it was organized in several parallel sessions, including some main Symposia, a couple of technical Workshops, and several sessions of contributed oral presentations (each about a common topic). Therefore, it was impossible attending to everything. I hope the reader forgives me if I focus mainly in what I’m interested in.

The meeting opened a day before the official date (28th), with a satellite meeting in Japanese in the morning (to which I did not attend for obvious reasons) and three oral sessions in the afternoon (in English), one of them mixing topics on neural development, system biology, technological and theoretical approaches. For a start, and given that it was not the official day 1 (but day 0…), the room was not full, but still there were some discussion and even a cute picture of a hibernating hamster (see below), presented by Torsten Bullmann, of RIKEN QBiC, about his work on the protein tau and its role on the plasticity of dendrites.

It was a surprise for some of the audience, since it seemed that tau is a very well known marker for axons… but Bullmann explained that it depends on its phosphorylation state and thus you can use different antibodies against tau to mark either axons or dendrites. Other quite interesting talk was that of Kenneth Ho et al., also from RIKEN QBiC, about the Systems Science of Biological Dynamics (SSBD) database that they have created and to which any scientist can upload published data or download them, so that everyone can use them. You can find the database and more information about it here. This database looks quite good, and is distinct from other databases that contain just sequence information. A set of tools to work with the images is also integrated into the database, such as ImageJ utilities. You can have a look at the database also in this video:

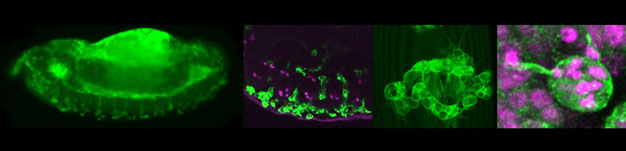

On the second day (official 1st day), I attended to the joint symposium between the Spanish Society for Developmental Biology (SEBD, standing for the Spanish name of the society) and the Japanese one. This was the first time that the JSDB held a joint symposium with a society from abroad, and I would say that it was a success. Great scientists from Spain joined the meeting, both senior and young. The talk by Ángela Nieto, from the Institute for Neurosciences in Alicante and president of the SEBD, on the role of snail and other transcription factors in epithelial-to-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transitions, not only during development but also during the metastatic process of cancer, woke up the curiosity of the audience in the early morning. Have a look to this great review by Nieto about this topic here. Of much interest was also the talk by Miguel Torres, from the National Center for Cardiovascular Research (CNIC) in Madrid, on how cells compete with each other to contribute to the embryonic development of mammals; and that of María Abad, from the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), also in Madrid, who talked about the in vivo generation of iPS cells. You can check the work by Torres here, and that of Abad, here. Ana Gradilla, a Mexican researcher who belongs to the SEBD, presented her work done at the Center for Molecular Biology Severo Ochoa (Madrid) about the very hot topic of the distribution of morphogens within exovesicles through cytonemes in Drosophila. The discussion on this work (check it out here) was also continued during a nice nijikai (Japanese word for after-party), the second day after the reception.

One important feature of this meeting was the high number of talks. Masahiko Hibi, the organizer of the meeting, said that the aim of the meeting was to give as many chances as possible to young researchers to give a talk. In this regard, there were two sessions of flash talks, one on each of the first two days, of 3 minutes of duration where the presenters had to introduce their work, and later on continue the discussions with those interested in the poster session. It was actually a success, since I haven’t seen such a lively poster session in any meeting so far. I’d like to highlight that of Yuichiro Hara, from RIKEN CDB, who presented about transcriptomic and genomic resources of the Madagascar ground gecko, a very interesting emerging model organism. They are now constructing a database, Reptiliomix, which contains these transcriptomics resources. Keep an eye on their lab website about the anticipated release of the web server.

After the flash talks I attended one of the workshops scheduled in the meeting (at the same time that two very nice oral presentation sessions, about Early Embryogenesis and Evo-Devo, and about Morphology – I wish I could have cloned myself to attend those-). I attended the workshop because I had to give a contributed talk there. This workshop was entitled “New Genome Technologies in Developmental Biology” and was organized by Atsuo Kawahara, from Yamanashi University and RIKEN QBiC, and by Takashi Yamamoto, from Hiroshima University. The workshop was basically focused in the most recent genome editing technology, such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system, a topic that was very present during the whole meeting, highlighting the importance of these very new techniques. However, my talk was about a comparative transcriptomics analysis between turtle and chicken tissues, including the carapacial ridge, the embryo’s structure controlling the shell formation.

The second day started with the two plenary lectures of the meeting. The first one, by Alex Schier from Harvard University, was about the role of a newly described gene, toddler, in the early embryogenesis of zebrafish. The second talk was by Hans Clevers, from the Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands who described Lgr5 as a marker for stem cells in the crypts of the intestinal epithelium. Clevers’ team could also generate intestinal organoids by controlling the expression of Lgr5, technology developed by this postdoctoral fellow Toshiro Sato. Clevers delighted the audience with beautiful animations, including those that represented clonal crypts from cells expressing different fluorescent proteins… eventually resulting in colorful intestinal epithelia. Both plenary talks were followed by many questions from the audience.

The afternoon of the second day was also followed by flash talks presentations, and after that the second workshop (“Frontiers in Developmental Biology by Unique Approaches”) and two parallel oral presentation sessions. In this case I decided to attend one of the oral sessions, about the Gene Expression and Epigenetics, where I attended an interesting talk about the differences in Shh regulation between chicken and mouse, by Takanori Amano, from the National Institute of Genetics of Japan.

Since a meeting does not consist only of science, but also of socializing events among scientists, the second day was finished by a very nice reception in a hotel near the meeting venue. It was a very relaxing time, and I could finally enjoy some time with my Spanish colleagues and discuss, among other things, about the situation of science in our country (not a very hopeful future, I would say). Some announcements that you might be interested in were about the next year’s JSDB meeting, to be held in Tsukuba, and organized by Hiroshi Wada, from the Tsukuba University; Ángela Nieto, as the president of the SEBD, announced the next meeting of the Spanish Society (together with the Portuguese Society of Developmental Biology) will be held in Madrid this year from October 13th to 15th, and it will be in association with the JSDB (there will be a couple of fellowships for young researchers to attend, so don’t forget to apply if you plan to attend!). Also, the next year’s JSDB meeting will hold a joint symposium with the Dutch Society for Developmental Biology (see this past post in the Node), in the same way that this year was with the Spanish counterpart.

The last day had 6 symposia, 3 in the morning and 3 in the afternoon. In the morning, I attended the symposium of the Asia-Pacific Developmental Biology Network, to have a glimpse of what is done in the region. I attended the talk of Xinhua Lin, at the Institute of Zoology from the Chinese Academy of Science, about tissue homeostasis by gut stem cells in Drosophila. And, finally, in the afternoon I went to the talk given by Benny Shilo, from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, about the dorso-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo.

Overall, it was a nice meeting, not too small, and not too big. In my case, I have been working for almost four years in Japan, and it has been my first national meeting, what have allowed me to get an idea of what Japan is up to. Given the fact that I am actually thinking about continuing my scientific career here, I could learn about different institutes, universities and researchers with whom I can collaborate in the future. However, the atmosphere is much more international than I expected, and thus even if you are not working in Japan, attending this meeting is definitely worthy. So, keep an eye on the upcoming meeting in 2015 in Tsukuba, and come if you have the chance. You will not regret it!

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (5 votes)

(5 votes) (2 votes)

(2 votes)