What’s the future of peer review?

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 3 January 2013

Jordan Raff’s recent Biology Open editorial on the future of publishing, posted on the Node, sparked quite a debate in the comments section. Much of that discussion focussed on perceived problems with the peer review system in scientific publishing. Particularly with the rise of journals like PLoS One and BiO, it seems that authors are increasingly dissatisfied with the time and effort – and with the sometimes cryptic decision-making – involved in publishing in more selective journals (journals whose selection criteria include some measure of ‘conceptual advance’ or ‘general interest’). I promised in one of my comments to Jordan’s post to write in more detail about my take on these issues, and what Development is trying to do to alleviate community concerns with the peer review process. So, here goes…

To start with what is perhaps an obvious point: one of the key aims of the peer review process is to improve the submitted paper, and in the vast majority of cases, I think it does just that – the finally accepted version of a manuscript tends to be both scientifically more sound and easier for the reader to understand than the original submission. Importantly, peer review – whether it’s of the more selective or the purely technical kind – provides some kind of quality assurance stamp on a published paper: although erroneous and fraudulent papers do end up being published, I’m sure there are far fewer of them in the public domain as a direct result of the peer review process.

However, that’s not to say that the system is perfect, because it certainly isn’t. Particularly with the rise of supplementary information, it’s all too easy for referees to ask for a ‘shopping list’ of experiments, many of which can be peripheral to the main story of the paper. And all too easy for editors to simply pass on those referee reports without comment – either because they’re too busy to go through the reports in sufficient detail to figure out what the really important points are, or because they don’t have the specialist knowledge to pass those judgments (which, after all, is why we need referees in the first place!). With a few tweaks to the system, we can do better than this.

For a selective journal, which Development unashamedly is, I think the key is to encourage referees to focus their reports on two things:

1. What’s the significance of the paper and why should it be of interest to the journal’s readership?

2. Do the data adequately support the conclusions drawn, or are there additional experiments necessary to make the paper solid?

With clear answers to those two questions in hand, it should be much easier for editors to decide firstly whether the paper is in principle suitable for the journal (spelled out in the answer to question 1), and secondly what the authors need to do for potential publication (the experiments given in response to question 2). It should get rid of that long list of ‘semi-relevant’ experiments (that aren’t really pertinent to q2), and it should make decisions much more definitive. There’s nothing worse than going through 2-3 rounds of extensive revision only for an editor to decide that the paper’s not worth publishing after all (something that, incidentally, Development is good at avoiding: around 95% of papers that receive a positive decision after the first round of review are published in the journal). Having a clearer (and shorter!) list of necessary revisions should help to avoid such situations.

I’m not a radical and I think it’s evolution not revolution of the system that’s required here. But I (and we at Development) do want to improve things. To this end, we’re looking at ways of changing our report form to reflect the aims laid out above. It might seem like a small step, but I genuinely believe that it could be a valuable one in easing the path to publication.

Moreover, I don’t think that the more radical alternatives work – various possibilities have been proposed and tested, but success is thin on the ground. Deposition in pre-publication servers and community commenting works very well in the physical sciences, but not in the biological sciences – as trials by Nature (see here and here) have demonstrated. Post-publication commenting could be a valuable addition to peer review, or even an alternative to it, but it just hasn’t taken off: I just looked at a random issue of PLoS Biology from 2012 and of the 17 papers published, only 3 had comments, none of which were particularly substantial. Open peer review – where referees sign their reports – would be great in an ideal world, but whenever I ask an audience if they’d be happy to sign their report if they were reviewing a paper for a top name in their field who might in turn be reviewing their next grant application, the vast majority opt to stay anonymous. It’s a competitive world out there, and scientists (like everyone else) hold grudges. Double-blind peer review – where the authors are also anonymous – might have some benefits in terms of reducing potential referee or editor bias, but it’s not easy to implement, and in most cases the referees will know who the authors are in any case.

So given the limitations of the alternatives, I believe that most journals will continue to operate some form of traditional peer review for the foreseeable future, and I don’t think this is a bad thing. That’s my opinion, but we also want to hear your views on this. What most frustrates you about the whole publishing process? Would a more streamlined review process like the one I’ve suggested help? What else can we do to make the system better?

Finally, though, there’s one thing that always comes to mind when I hear people complaining about the review process. You as authors are also the reviewers (or if you aren’t yet, then you one day will be) – meaning that you’re the ones giving ‘unreasonable’ lists of experiments to other people. It’s easy to pick holes in a paper, but harder to recognise when the authors have already done enough. So when you put on your reviewing hat, remember how you felt about the anonymous hyper-critical reviewer of your own paper so you don’t risk turning into one of them!

(6 votes)

(6 votes) (3 votes)

(3 votes) Node news

Node news We heard about some exciting research this last month of the year. In an

We heard about some exciting research this last month of the year. In an

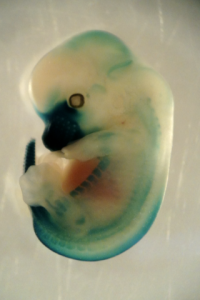

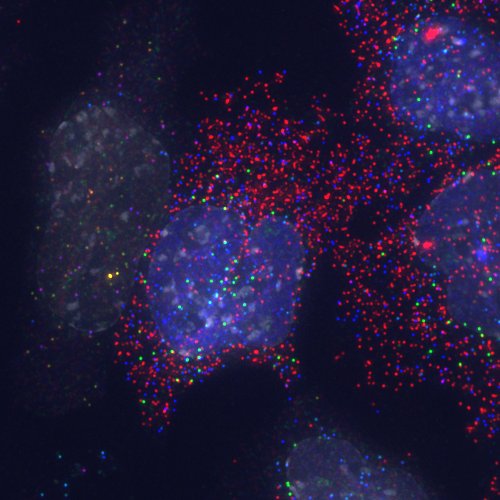

In 1953, Alan Turing, a mathematician who had enabled the allies to break the Nazi communication codes – thereby making a significant contribution to ending the war in Europe – turned his attention to biology. Acknowledging the chemical make-up of living systems, he wondered what kind of reactions could generate the spatial patterns that are so pervasive in the outer layers of plants and animals. He noted that carefully coordinated interactions between an activator and an inhibitor, coupled to their diffusion, would, under certain conditions, be able to generate stable patterns of spots and stripes that resemble some of those found in nature. This simple chemical circuit had the potential to explain many phenotypes and as such has received attention over the last 50 years, although Turing himself only studied it as a proof of principle.

In 1953, Alan Turing, a mathematician who had enabled the allies to break the Nazi communication codes – thereby making a significant contribution to ending the war in Europe – turned his attention to biology. Acknowledging the chemical make-up of living systems, he wondered what kind of reactions could generate the spatial patterns that are so pervasive in the outer layers of plants and animals. He noted that carefully coordinated interactions between an activator and an inhibitor, coupled to their diffusion, would, under certain conditions, be able to generate stable patterns of spots and stripes that resemble some of those found in nature. This simple chemical circuit had the potential to explain many phenotypes and as such has received attention over the last 50 years, although Turing himself only studied it as a proof of principle.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) If you have been following along with the

If you have been following along with the