Dear Reader,

My name is Dávid Molnár, I’m a third year Ph.D. student in the Department of Human Morphology and Developmental Biology at Semmelweis University (Budapest, Hungary). I’d like to share the story of my summer internship with You!

Thanks to the generous offer of Guojun Sheng, the team leader of the Laboratory for Early Embryogenesis in RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology (Kobe, Japan), I could spend three months in his lab in a Japanese world leading institute. It changed my working progress, my view on science and the way how I got there taught me a lot.

|

|

in the front: Guojun Sheng

in the background: Cantas Alev and Ruben Buys

|

Almost a year ago in September of 2009, I lived the ordinary life of Hungarian Ph.D. students. The preparation for the ISDB 2009 conference brought a little excitement into my days and started a series of unpredicted events. Those days were also unique for me, because that was the first time in my life when I travelled by plane.

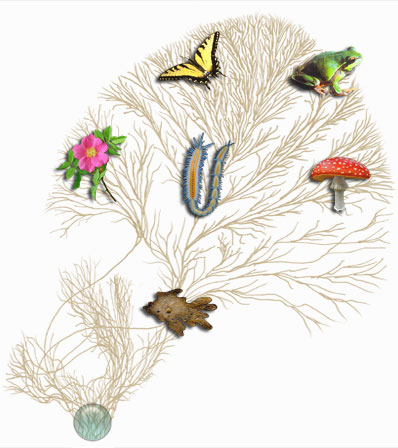

In the charming city of Edinburgh I met many people, who had just been well known names on the headers of articles before, but there I saw the persons themselves behind the papers. In the labyrinth of the exhibitors’ stands I found the desk of RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology. I had known before that it was a melting-pot of scientists from all over the world studying developmental biology on advanced level but at that time , due to my lack of foreign research experience, I couldn’t imagine how this kind of institute worked. I took a RIKEN brochure. At the end of the conference I realized that my baggage was heavy, so I started sorting out all the papers and tearing out the useful pages. That was the moment when I saw a report of Brendan McIntyre’s work who was a post doc in Dr. Sheng’s lab. The key words “blood, hematopoiesis, CD34, chicken embryo” aroused my interest immediately.

After the conference several weeks elapsed until I read those torn pages again. That time we just started introducing in situ hybridization to our techniques. We were interested in different hematopoietic markers e.g. CD34, but there was no commercial antibody against the chicken equivalent of this protein, and we were not that experienced in molecular biology methods. I sent an e-mail to Brendan McIntyre who was really helpful. He had already left Japan but answered my questions and forwarded my e-mail to team leader Guojun Sheng. From that time we exchanged plenty of letters with Dr. Sheng in which he shared all his remarks and advice about the ideas and experiments we were planning.

Surprisingly in late February I got an e-mail form Dr. Sheng: he offered me a short time internship in his laboratory in the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology.

Then a hurrying organization started with visa application, obtaining the certificate of eligibility, exchanging letters, photos numerous documents. Because my financial sources were limited I had to look for external funding. Coincidentally one of my collegues after a lunch break mentioned an application which supports young researchers. We checked it out together – it was the Development Travelling Fellowship. First I estimated a low chance to receive the scholarship, but I convinced myself to try it. Getting closer and closer to the 1st of June, the determined date of departure, I got more and more excited. Nearly one week before my trip I got the result: I would get support from Development. It was unbelievable how lucky I was!

In less than a year I ended up with an invitation to Japan and a successful grant application, and soon after my first flight I got the chance to travel by plane again – immediately to the other half of the world. Since then I’ve been frequently thinking about what had happened if I hadn’t taken a brochure, if I hadn’t taken those torn pages, if I hadn’t been brave enough to write an e-mail to Dr. Sheng. The main conclusion of the previous year: always go with eyes wide open, because you never know what sort of chances will be served by life!

|

| The turtle eggs have just arrived! |

My experiences in Japan absolutely fit into this series of successful events. In Guojun Sheng’s lab I spent three hard-working months under the supervison of Cantas Alev. During this time I tasted a little molecular biology in the fascinating environment of RIKEN CDB. I learned how to generate in situ probes and carry out whole mount in situs. I worked on No1 machines in the company of great scientists. Of course I traveled around the Kansai area and I managed to visit Okinawa too, but the main advantage of my stay – beside its scientific impact- is that I got to know how life goes on in Japan. At RIKEN CDB I experienced the atmosphere of high level science outside the institute I saw a peaceful and safe country with delicious food, inspiring history, beautiful geography and I was surrounded by kind and friendly people. I really enjoyed it and it’s easy to get used to it!

Unfortunately my internship finished just when I felt the people around me were pretty close to myself and work raised the possibilities of different projects. Nowadays I usually think about my friends who I met in Japan.

This year taught me to look for the chances and to be brave enough to use them, to realize the necessity of foreign experiences and how to fit to a changed environment.

I’m really thankful to Guojun Sheng and Cantas Alev. Their support brought me one step closer to molecular biology and extended my view on other fields of developmental biology. I truly believe that this three-month internship opened new doors which may result in a long-time collaboration between the two laboratories.

At last but not least I must say thank you to each and every member in the Laboratory for Early Embryogenesis (in alphabetical order): Cantas Alev, Manjula Brahmajosyula, MengChi Lin, Hiroki Nagai, Yukiko Nakaya, Fumie Nakazawa, Kanako Ota, Guojun Sheng, Erike Sukowati, Wei Weng, Yu Ping Wu. I’m also thankful to Ms. Naoko Yamaguchi who helped arrange the visit.

Finally I’d like to express my gratitude to all those at The Company of Biologists and Development who spent time on reading my application and supported my plan to come true!

|

|

| Kobe – Harborland |

Laboratory for Early Embryogenesis – RIKEN CDB – Kobe, Japan

Developmental Biology and Immunology Lab – Department of Human Morphology and Developmental Biology, Semmelweis University – Budapest, Hungary

(5 votes)

(5 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(3 votes)

(3 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Most POU family transcription factors are temporally and spatially restricted during development and play pivotal roles in specific cell fate determination events. Oct1 (Pou2f1), however, is ubiquitously expressed in embryonic and adult mouse tissues; so, does Oct1 have a developmental role? On p.

Most POU family transcription factors are temporally and spatially restricted during development and play pivotal roles in specific cell fate determination events. Oct1 (Pou2f1), however, is ubiquitously expressed in embryonic and adult mouse tissues; so, does Oct1 have a developmental role? On p.  How neurons connect to their targets during embryogenesis has been intensively studied, but what maintains the position and connections of nerves during postembryonic growth? To investigate this, William Talbot and colleagues study the development of the posterior lateral line nerve (PLLn) in zebrafish embryos and larvae (see p.

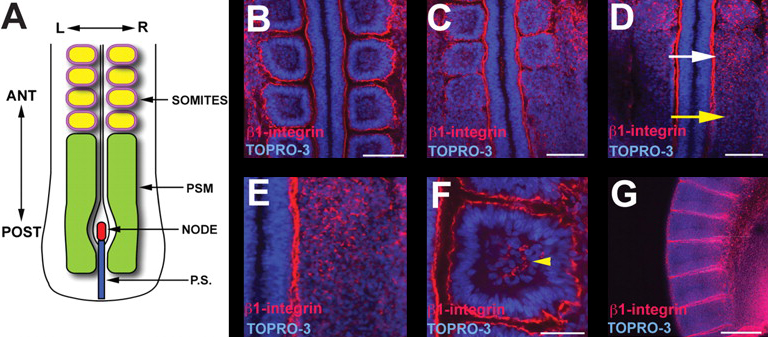

How neurons connect to their targets during embryogenesis has been intensively studied, but what maintains the position and connections of nerves during postembryonic growth? To investigate this, William Talbot and colleagues study the development of the posterior lateral line nerve (PLLn) in zebrafish embryos and larvae (see p.  Plant stem cell populations are maintained by the precise coordination of stem cell division and the rates of cell division and differentiation among stem cell progenitors. In the growing tips of higher plants (shoot apical meristems, SAMs), stem cell daughters produced by infrequent stem cell division in the central zone (CZ) are displaced towards the surrounding peripheral zone (PZ), where they divide faster and their progeny differentiate into leaves or flowers. Now, Venugopala Reddy and co-workers report that the homeodomain transcription factor WUSCHEL (WUS) mediates stem cell homeostasis in Arabidopsis (see p.

Plant stem cell populations are maintained by the precise coordination of stem cell division and the rates of cell division and differentiation among stem cell progenitors. In the growing tips of higher plants (shoot apical meristems, SAMs), stem cell daughters produced by infrequent stem cell division in the central zone (CZ) are displaced towards the surrounding peripheral zone (PZ), where they divide faster and their progeny differentiate into leaves or flowers. Now, Venugopala Reddy and co-workers report that the homeodomain transcription factor WUSCHEL (WUS) mediates stem cell homeostasis in Arabidopsis (see p.  Haematopoietic clusters – cell aggregates that are associated with endothelium in the large blood vessels of midgestation vertebrate embryos – play a pivotal but poorly understood role in the formation of the adult blood system. To date, the opaqueness of whole embryos has prevented the systematic quantitation or mapping of all the haematopoietic clusters in mouse embryos but, on p.

Haematopoietic clusters – cell aggregates that are associated with endothelium in the large blood vessels of midgestation vertebrate embryos – play a pivotal but poorly understood role in the formation of the adult blood system. To date, the opaqueness of whole embryos has prevented the systematic quantitation or mapping of all the haematopoietic clusters in mouse embryos but, on p.  During development, extensive remodelling of the embryonic vasculature, the first organ to develop, ensures that the embryo’s cells are constantly supplied with oxygen and nutrients. The first major vascular remodelling event in mammalian and avian embryos is fusion of the bilateral dorsal aortae at the midline to form the dorsal aorta. Takashi Mikawa and co-workers now show that a developmental switch in notochord activity signals this fusion in chick and quail embryos (see p.

During development, extensive remodelling of the embryonic vasculature, the first organ to develop, ensures that the embryo’s cells are constantly supplied with oxygen and nutrients. The first major vascular remodelling event in mammalian and avian embryos is fusion of the bilateral dorsal aortae at the midline to form the dorsal aorta. Takashi Mikawa and co-workers now show that a developmental switch in notochord activity signals this fusion in chick and quail embryos (see p.  In insects that completely metamorphose, such as Drosophila, embryonically specified imaginal cells remain dormant until the larval stages when their coordinated proliferation and differentiation generates various adult organs. Now, on p.

In insects that completely metamorphose, such as Drosophila, embryonically specified imaginal cells remain dormant until the larval stages when their coordinated proliferation and differentiation generates various adult organs. Now, on p.