The evolution of an axon guidance model: from chemotaxis to haptotaxis

Posted by Samjbutler, on 16 May 2017

The canonical model

The publication of Marc Tessier-Lavigne’s seminal Cell papers (1, 2) in 1994 describing the identification of netrin1 (from the Sanskrit word, netr, meaning “one who guides”) was a defining moment in my graduate career. My friends and I talked about those papers for weeks, from the incredible technical feat, the biochemical purification of netrin1 from tens of thousands of chicken brains, to the commonality of the neural developmental mechanism, based on the homology of netrin1 with Unc6, a gene previously identified by Ed Hedgecock and Joe Culotti in a C.elegans screen for axon guidance defects (3).

A couple of years later, I interviewed for postdoctoral positions in San Francisco Bay area in neural development laboratories, and had arranged to stay with Marya Postner, a fellow Princeton graduate alumnus. Marya just happened to be married to Tito Serafini, who, with Tim Kennedy, was one of two lead postdocs on the seminal 1994 Cell papers. Tito was still working with Marc at the time. I asked him breathlessly about the status of the netrin1 project – did they have a netrin1 loss of function phenotype yet? Tito looked happy, triumphant even. “Yes!” he said. “We’ve knocked out the mouse homologue. Commissural axons stall before they reach the floor plate.”

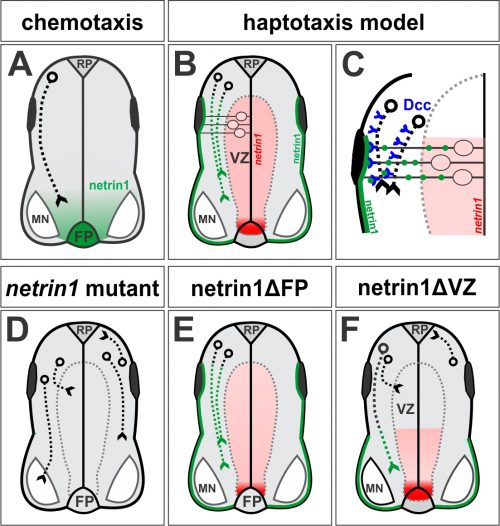

This Cell paper came out a couple of months later (4) and cemented the idea of chemotaxis as the prevailing model of axon guidance (5): netrin1 is secreted from floor plate (FP) cells at the ventral midline of the spinal cord, and like a beacon in a harbor guiding ships in the night, orients commissural axons to grow towards it (Fig. 1A). This model fit with insight dating back as far as Cajal (6), including work performed in grasshoppers (7, 8) and then in vertebrates (9, 10). Together, these studies suggested that axons could be guided in a stepwise manner over long distances by chemotropic attractive or repellent cues diffusing from “guidepost” cells that they encountered along the way. The axon guidance field also recognized that axons also grew on local substrates provided by extracellular matrix components, such as laminin. But their contribution was generally considered prosaic, i.e. passive carpets that permitted or prevented axon growth. The more important and interesting contribution to neural circuit formation came from the chemotropic cues, the netrins, semaphorins, the slit/robo pathway and morphogens.

Problems with the chemotropic model for netrin1

I have taught the chemotropic model of axon guidance for years in my undergraduate and graduate lectures, with netrin1 as the centerpiece discovery. It was a beautiful example of scientific daring being rewarded with mechanistic understanding. I was able to trace a path from the first century-old scientific insight to the netrin1 mutant phenotype that strongly supported that hypothesis.

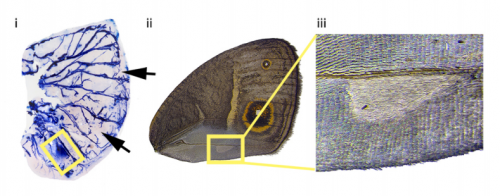

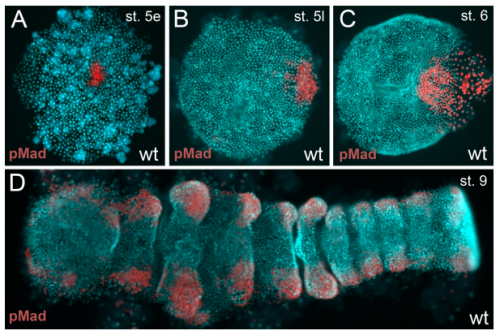

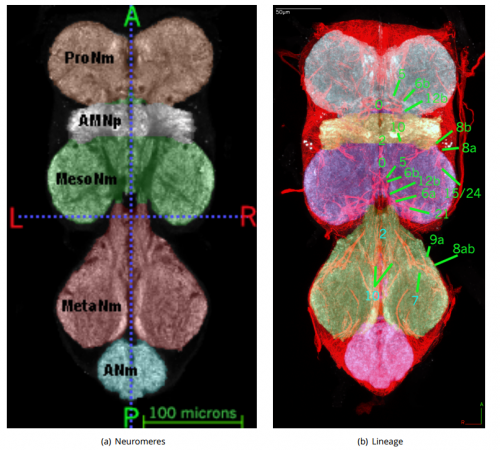

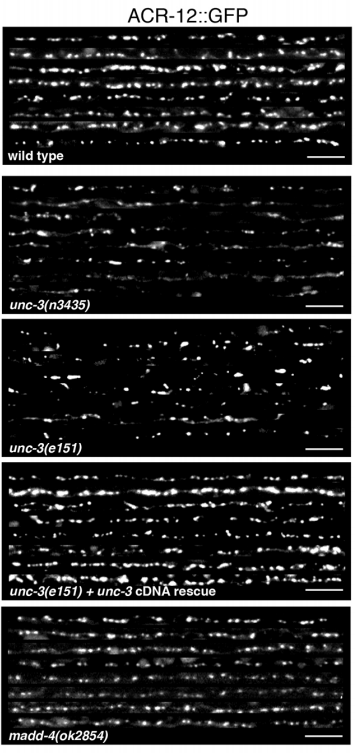

However after starting my own laboratory in 2004, I began to wonder about a reported, but underappreciated, feature of the netrin1 expression pattern. Textbooks often show the distribution of netrin1 in the chicken spinal cord, where netrin1 is expressed at high levels specifically in the FP. However, my first undergraduates – Joe Herrold and Anna Maglunog – found that mouse netrin1 is also expressed in the ventricular zone (VZ), which is the central compartment where the neural progenitor cells reside, oscillating back and forth on radial process as they proliferate. Spinal axons uniformly avoid growing in the VZ, staying rather at the “sides” of the spinal cord in a region that will ultimately segregate into the grey and white matter. Anna found that netrin1 expression extended into the dorsal VZ and appeared to strengthen, rather than diminish, over time (Fig. 1B).

This distribution had been accurately described in Serafini et al (4). But, it remained unresolved why spinal commissural axons first grew around the domain of VZ-derived netrin1 before growing towards FP-derived netrin1 (Fig. 1A). Were commissural axons unresponsive to ventricular netrin1? In that case, how did commissural axons then become responsive to FP-derived netrin1 to grow towards the ventral midline? Was there a molecular switch that controlled this process? Joe also noticed that in netrin1 mutant mice, while the vast majority of commissural axons of the Tag1+ subtype stalled as they entered the ventral spinal cord as published (4), there were always some Tag1+ axons that entered the VZ. Again, this latter phenotype was reported by Serafini et al, but it was not a major focus of the paper. We also wondered why spinal axons usually grew around the VZ. Was there a repellent in the VZ? Could netrin1 be that repellent?

I wrote some of these ideas into an R01 grant application that was eventually funded in 2008, which allowed me to bring a postdoctoral fellow on board to work on these questions. However, the project stalled for two years; the Tag1+ axon mispolarization phenotype was subtle and it remained stubbornly unclear whether these axons originated from within the spinal cord or from the dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) in the adjacent peripheral nervous system. Moreover, my plan to tackle the problem by recapitulating the putative VZ-repellent activity in a tissue co-culture assay proved challenging. No progress was made and alas, the postdoc left my lab. With time running out to fulfill this aim of my grant, I recruited a student, Supraja (Sup) Varadarajan onto the project with the idea that she could complete the characterization of the netrin1 phenotype. It would be a quick paper, I reassured her. One of the first ideas that we had was to characterize the netrin1 mutant using a wider range of axonal markers.

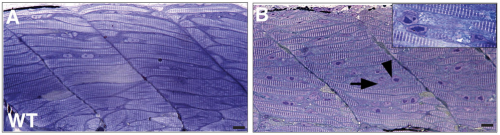

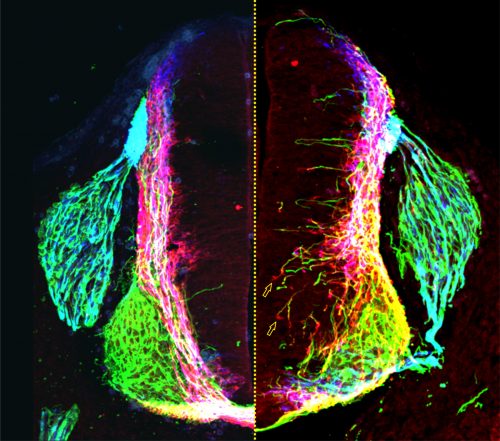

First moment of clarity: many types of spinal axons invade the VZ in netrin1 mutants

Not long afterwards, Sup called me over to her computer very excitedly: “LOOK at the pattern of neurofilament innervation!” she said. Neurofilament (NF) is an intermediate filament present ubiquitously in axons. Sup had made transverse slices of control and netrin1 mutant spinal cords and stained them with antibodies against NF. While control NF+ axons grew their usual orderly way avoiding the VZ, to our amazement we saw that NF+ axons were now profusely growing into the VZ in the netrin1 mutant (Fig. 1D, Fig. 2). Antibodies against another protein, Robo3, which labels all commissural axons, showed a similar phenotype; axons were no longer tightly bundled or fasciculated. Rather, the axons radiated in all directions, including into the VZ (Fig. 2). Thus, the observed stall of Tag1+ commissural axons appeared to be an anomaly: the loss of netrin1 resulted in other spinal axons extending wildly into the VZ. We suddenly had clear evidence that there might be a repellent in the VZ, with netrin1 as a top candidate for that repellent.

Sup then spent considerable time mapping domains of netrin1 expression in the mouse spinal cord at different stages of development. She found two general patterns of behavior: 1) spinal axons rarely grow on netrin1-expressing cells, and 2) spinal commissural axons grow precisely around the boundary of netrin1-expressing cells in the VZ. But were these activities mediated by a long-range activity from the FP or a more local, short-range activity from the VZ? Our genetic manipulations strongly supported the presence of a VZ-derived netrin1 repellent. First, we characterized Gli2 mutants, which have no FP (12) either singly or in combination with a netrin1 mutation. The result was clear-cut – it was not enough to remove the FP; NF+ axons only invaded the VZ in the absence of VZ-derived netrin1. Second, in collaboration with Jennifer Kong and Bennett (Ben) Novitch, we were able to ablate netrin1 expression from a stripe of neural progenitor cells, thereby creating two de novo netrin1(-):netrin1(+) boundaries. To our amazement, axons now detached from their normal trajectories and extended into the VZ to follow along one of the ectopic boundaries of netrin1 expression. Everyone in the Butler/Novitch joint lab meeting applauded when Sup showed these results for the first time.

Revised model: netrin1 provides a growth boundary for axon extension

Our first model was that netrin1, present in the VZ, was repulsive for axon growth. But our results were now suggesting a more complex activity. While spinal axons did generally avoid growing on netrin1-expressing cells, commissural axons appeared to grow preferentially along a netrin1(-): netrin1(+) boundary. Since there wasn’t an obvious term for this phenomenon, which was unwieldy to constantly explain, Sup came up with the concept of a “hederal” boundary. Ivy (genus, hedera) uses a wall (c.f. netrin1) as a necessary scaffold for growth, but it is unable to penetrate this wall as it grows. We wondered whether this hederal activity of netrin1 was more attractive or more repulsive, and tested this idea by examining mice lacking different classes of netrin1 receptors, sent to us by Artur Kania.

In the canonical model, netrin1 results in attractive or repulsive responses in axons by activating different receptor complexes. Thus, Dcc translates the attractive responses of netrin1 (13), whereas the Unc5 family mediates the repulsive responses (14). I was confident we would find that a member of the Unc5 family decoded the netrin1 growth boundary in axons, thus confirming that we were describing a repellent activity. But I was wrong: Sup found only minor axon guidance phenotypes in the Unc5 mutants, many of which had been reported before, and stemmed from the loss of Unc5 expression in the DRGs. However, the Dcc mutants looked just like the netrin1 mutants: Tag1 axons stalled, as already described (13) and NF and Robo3 axons dramatically extended into the VZ (Fig. 1D). Thus, Dcc appears to be the chief receptor that mediated the ability of spinal axons to avoid the VZ, and grow alongside a netrin1(-):netrin1(+) border. Moreover, these findings suggested that netrin1-Dcc might be working through an attractive, rather than repulsive, mechanism.

Second moment of clarity: netrin1 protein is deposited on the pial surface of the spinal cord where it acts as a haptotactic growth substrate

As we started to write the paper, Sup had a thesis committee meeting with Kelsey Martin, Alvaro Sagasti and Larry Zipursky where she was questioned skeptically about the feasibility of our hederal model. Larry, in particular, wanted to know more about the distribution of netrin1 protein. Larry, working with his postdoc Orkun Akin, had just shown that netrin had an adhesive, rather than chemotropic, role in the fly medulla (15). We grudgingly admitted that we had never looked, because we had no expectation that netrin1 protein would be anywhere other than the VZ. A couple of days later, Sup appeared at my door, looking worried. “The staining doesn’t look right,” she said. “There’s a lot of background staining on the pial surface of the spinal cord, and in axons.” I internally cursed the non-specificity of our antibody. “Try antigen retrieval.” I said, “That’s what Tim Kennedy had to do!” (16). Sup came back a day or two later, looking even more worried, and told me that the antigen retrieval protocol made the staining “worse.” Both the pial and axonal staining looked brighter than ever. “It looks real!” she said glumly. This distribution made no sense in our model, and I complained to Larry about his opening up a can of worms, when I saw him at a seminar that afternoon. “It’s a bad molecule,” Larry joked.

Sup was right; the antibody staining did look real. There were very low levels of netrin1 in the VZ as we had predicted, but there were much higher levels on most of the pial surface around the circumference of the spinal cord, and on axons (Fig. 1B). I showed James Briscoe the distribution pattern when he visited UCLA a couple of weeks later. “Of course it’s real,” he said, “The neural progenitor cells are making netrin1, and then depositing it on the pial surface using their radial endfeet.” We corralled Ben in from his office next door to mine to assess what he thought. He thought the staining was real too. The three of us peered excitedly at my computer screen, the realization of how the pattern of the netrin1 transcript related to the distribution of netrin1 protein slowly sinking in. We then discussed nothing else for the rest of the weekend.

Sup went on to show that indeed James’ supposition was correct. Through a trick of their cellular geometry, the neural precursors that make netrin1 then use their radial processes to deposit it as a growth substrate onto the pial surface (Fig. 1B, C). No netrin1 is made by the dorsal-most neural precursors, and indeed there is no netrin1 on the most dorsal pial surface. Sup pointed out that the resulting sharp on:off netrin1 boundary on the dorsal pial surface really suggested that netrin1, a member of a laminin family, could not be highly diffusible. In other exhilarating moments of understanding, we realized that spinal neurons specifically initiate NF+ axonal growth on this netrin1 pial-substrate. And that netrin1 only accumulates on commissural axons as they grow adjacent to the netrin1 pial-substrate, as if netrin1 can transfer from this substrate to axons. In a further remarkable result, Sup found that the putative axonal-transfer of netrin1 requires Dcc.

We finally understood how to model our results: VZ-derived netrin1 acts locally as a substrate to promote fasciculated axonal growth in an oriented manner towards the ventral midline. Netrin1 and Dcc appear to cooperate within axons as part of the mechanism that orients growth (Fig. 1C). The innervation of the VZ that we had observed in both netrin1 and Dcc mutants might in fact be randomized, or defasciculated, growth as a result of losing this adhesive interaction (Fig. 1D). VZ-derived netrin1 thus appears to act by haptotaxis, i.e. by the establishment of a local adhesive surface, the alternative model to chemotaxis. As a mechanistic side note: it remains unclear how this adhesive surface acts to orient and fasciculate commissural axon growth and whether there is an additional “no go” activity in the VZ. Is this mechanism functioning solely through haptotaxis? Or is there also a “hederal” component? Nonetheless, these activities – the pull of an adhesive substrate that promotes fasciculation, perhaps coupled with the push of a “no go” signal – permit axons to grow along the netrin1(-):netrin1(+) border, i.e. in a circumferential path precisely around the VZ.

Third moment of clarity: FP-derived netrin1 is dispensable for axon guidance

Our model – the ability of neural progenitor cells to deposit a haptotactic substrate of netrin1, which promotes ventrally-directed, fasciculated axon growth – was a notable departure from the textbook view of netrin1. But was this model the only mode of action? Or did netrin1 have long-range or short-range activities depending on the cell type? In his original papers, Marc Tessier-Lavigne argued the case for and against netrin1 acting by chemotaxis or haptotaxis (1), but ultimately settled on the idea, well supported by the data at the time, that netrin1 was presented as a long-range cue from the FP. I discussed this point vigorously and endlessly with Sup, Ben, Artur, Larry and Orkun. We had not doubted this model until now. Could our phenotypes still be explained by a long-range activity from the FP? Were the activities of short-range VZ-derived netrin1 in addition to the long-range activities? Or could FP-derived netrin1 really be dispensable for axon guidance?

In the end, the reviewers decided it. The beauty of the finding that neural progenitor cells lay down a substrate of netrin1 that orients and promotes the axonal trajectories of their own neural progeny was not considered sufficiently novel. It was clear what experiment needed to be done, thus we requested the conditional netrin1 lines from Holger Eltzschig and set about breeding them to Cre recombinase driver lines that would remove netrin1 specifically from either FP cells (ΔFP, Fig. 1E) or the dorsal VZ (ΔVZ, Fig.1F). Sup accomplished her breeding scheme astonishing quickly and the day came when she finally had the answer sitting on a microscope slide. I ran to the confocal room, both anxious and excited, to discover the result. “There’s no effect,” she said. “It doesn’t matter if you remove netrin1 from the FP!” In contrast, removing netrin1 from the VZ had profound effects. Axons grew in all directions, but only locally, specifically in the region where netrin1 had been removed from the VZ. Together with the Gli2-mediated FP ablation data, our studies had found no evidence for long-range chemotaxis in the spinal cord. Who knew? Perhaps Cajal’s model was wrong!

The paper was finally accepted at Neuron (11), and came out at the same time as a paper from Alain Chedotal in Nature (17), with complementary findings in the hindbrain. A few days later, I ran into a colleague on the street onside my lab. “I saw your paper in Neuron!” she laughingly scolded me, “But please don’t tell me I have to change my lecture on netrin1! I liked that lecture!” I liked my lecture on netrin1 too, but now I also have to change it. Netrin1, of course, remains the supreme architect of spinal circuitry, but now acts locally as a directional surface along which axons can extend, akin to the holds used by climbers to pioneer their way to the top of a mountain.

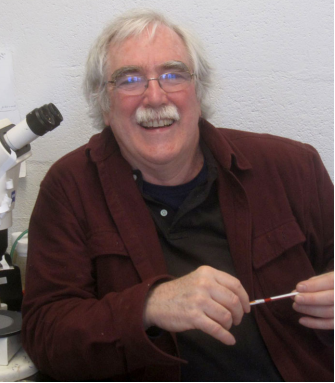

Samantha Butler

Department of Neurobiology,

Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research,

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center

University of California, Los Angeles.

References

1. Kennedy TE, Serafini T, de la Torre JR, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrins are diffusible chemotropic factors for commissural axons in the embryonic spinal cord. Cell. 1994 Aug 12;78(3):425-35. PubMed PMID: 8062385.

2. Serafini T, Kennedy TE, Galko MJ, Mirzayan C, Jessell TM, Tessier-Lavigne M. The netrins define a family of axon outgrowth-promoting proteins homologous to C. elegans UNC-6. Cell. 1994 Aug 12;78(3):409-24. PubMed PMID: 8062384.

3. Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Thomson JN, Perkins LA. Axonal guidance mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans identified by filling sensory neurons with fluorescein dyes. Dev Biol. 1985 Sep;111(1):158-70. PubMed PMID: 3928418.

4. Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996 Dec 13;87(6):1001-14. PubMed PMID: 8978605.

5. Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 1996 Nov 15;274(5290):1123-33. PubMed PMID: 8895455.

6. Ramón y Cajal S. Histology of the nervous system of man and vertebrates. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

7. Bentley D, Caudy M. Pioneer axons lose directed growth after selective killing of guidepost cells. Nature. 1983 Jul 7-13;304(5921):62-5. PubMed PMID: 6866090.

8. Ho RK, Goodman CS. Peripheral pathways are pioneered by an array of central and peripheral neurones in grasshopper embryos. Nature. 1982 Jun 03;297(5865):404-6. PubMed PMID: 6176880.

9. Placzek M, Tessier-Lavigne M, Jessell T, Dodd J. Orientation of commissural axons in vitro in response to a floor plate-derived chemoattractant. Development. 1990 Sep;110(1):19-30. PubMed PMID: 2081459.

10. Tessier-Lavigne M, Placzek M, Lumsden AG, Dodd J, Jessell TM. Chemotropic guidance of developing axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Nature. 1988 Dec 22-29;336(6201):775-8. PubMed PMID: 3205306.

11. Varadarajan SG, Kong JH, Phan KD, Kao TJ, Panaitof SC, Cardin J, Eltzschig H, Kania A, Novitch BG, Butler SJ. Netrin1 Produced by Neural Progenitors, Not Floor Plate Cells, Is Required for Axon Guidance in the Spinal Cord. Neuron. 2017 Apr 20. PubMed PMID: 28434801.

12. Matise MP, Epstein DJ, Park HL, Platt KA, Joyner AL. Gli2 is required for induction of floor plate and adjacent cells, but not most ventral neurons in the mouse central nervous system. Development. 1998 Aug;125(15):2759-70. PubMed PMID: 9655799. eng.

13. Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Hermiston ML, Tighe RV, Steen RG, Small CG, Stoeckli ET, Keino-Masu K, Masu M, Rayburn H, Simons J, Bronson RT, Gordon JI, Tessier-Lavigne M, Weinberg RA. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc) gene. Nature. 1997 Apr 24;386(6627):796-804. PubMed PMID: 9126737.

14. Leonardo ED, Hinck L, Masu M, Keino-Masu K, Ackerman SL, Tessier-Lavigne M. Vertebrate homologues of C. elegans UNC-5 are candidate netrin receptors. Nature. 1997 Apr 24;386(6627):833-8. PubMed PMID: 9126742.

15. Akin O, Zipursky SL. Frazzled promotes growth cone attachment at the source of a Netrin gradient in the Drosophila visual system. eLife. 2016 Oct 15;5. PubMed PMID: 27743477. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5108592.

16. Kennedy TE, Wang H, Marshall W, Tessier-Lavigne M. Axon guidance by diffusible chemoattractants: a gradient of netrin protein in the developing spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2006 Aug 23;26(34):8866-74. PubMed PMID: 16928876.

17. Dominici C, Moreno-Bravo JA, Puiggros SR, Rappeneau Q, Rama N, Vieugue P, Bernet A, Mehlen P, Chedotal A. Floor-plate-derived netrin-1 is dispensable for commissural axon guidance. Nature. 2017 Apr 26. PubMed PMID: 28445456.

(16 votes)

(16 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

In this issue (p.

In this issue (p.  In this issue (p.

In this issue (p.

(2 votes)

(2 votes) NEUBIAS, the Network of European

NEUBIAS, the Network of European