Many of you are probably familiar with the web comic Piled Higher and Deeper (PhD), which chronicles the lives of graduate students and perceptively points out some of the peculiarities of academia. Recently, we met up with the comic’s creator, Jorge Cham, and talked about graduate school, recognizable academic situations that cross all disciplines, and procrastination.

(Thanks to Node readers Kat, Pablo, and Sandra for providing some of the questions.)

When did you start drawing Piled Higher and Deeper?

I started during my first term in grad school, so I was definitely not supposed to be drawing comics. I was a teaching assistant, I was a research assistant, I was taking classes – but I saw this ad in [The Stanford Daily] newspaper calling for comics, and I just thought I would submit something nobody had ever really written about or made fun of: people trying to get their PhDs.

How did you manage to find time to combine that with grad school itself?

I didn’t sleep a lot during that semester! But I started publishing a new comic five days a week, and that quickly became only three times a week.

Many of your readers, including myself, grew up with your comic throughout grad school. Meanwhile, some of us have graduated, but a lot of your characters still haven’t. Are they ever going to graduate?

Yeah, the series will not go on indefinitely. I definitely have endings or events for all of the characters, whether they graduate or not.

Will there be a spin-off postdoc comic then?

Heh! Well, they might become postdocs. One of the characters is now a postdoc, but it will probably still be called “Piled Higher and Deeper”

We noticed that the comic works well for a lot of different fields. The readers of the Node are all developmental biologists, and you don’t have a biologist character in the PhD comics, but a lot of the things are still recognizable. Do you notice that a lot of the situations you write for, for example, the engineer characters are applicable to any field?

I do it on purpose. When I first started grad school I happened to know a lot of people who were in many different fields: Anthropologists, economists, engineers, geophysicists – and they were all friends! Just listening to them I could tell that they were all sharing the same experience. So for me, from the very beginning that was something that was interesting to me, so that’s the way I wrote the comics. I grounded the characters in a specific department, so that there’s a bit of realism there, and you get the sense that they are doing something. But I try to write the dialogue so that it generally speaks to academics and grad students in all disciplines.

That being said, there are specific things that biologists have to deal with that don’t occur in other fields, like the fact that you have to take care of living things on the weekend. Has anyone ever requested a biologist character?

Yeah, a lot. In fact, I’m very familiar with the idea of being beholden to experiments like that, because I worked in a neuroscience lab for two years. Somebody once described it as “your life being run by the menstrual period of rats”. I have a character who is going to focus on biology, but probably not for another year or year-and-a-half.

You also travel around to give talks about procrastination. A lot of visitors to the Node drop by during a break from work, and I’m sure they’d like to know if there’s any value to procrastination.

I don’t like to talk about whether procrastination is good or bad. I just like to talk about the fact that you do it, and that you probably do it for a reason. There’s a lot of flexibility in grad school, and it always feels like it never ends. There’s always something more that you could be doing – something more that you should be doing –so a lot of times people find themselves procrastinating. What I like to say is that procrastination is not necessarily bad, but that it’s sometimes an important part of the creative process, and can reveal what you really want to do, and what your real passions are. If you find that you’re not spending as much time as you should be on, for example, writing this particular chapter for this particular professor, it maybe means that you don’t really want to write it. Instead of feeling bad about it, you should just realize it, and focus on something else.

Finally, one of our readers in South America asked when you’re coming to the Southern Hemisphere

You just have to invite me – that’s pretty much how it works!

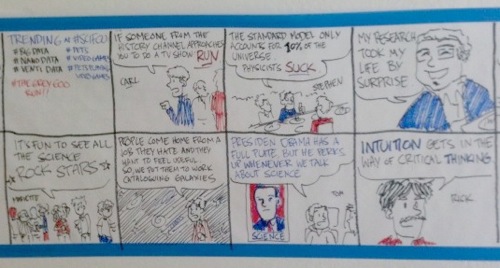

Part of a collection of panels Jorge drew at Sci Foo, where we met for the interview.

Part of the interview in audio format:

[audio:https://thenode.biologists.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/jorge-cham.mp3|titles=jorge cham]

(7 votes)

(7 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(3 votes)

(3 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

What path did you follow in your early career?

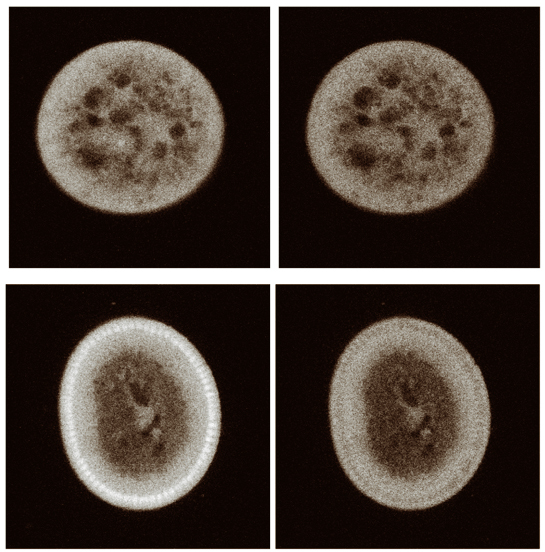

What path did you follow in your early career? Morphogen gradients provide key positional information during embryogenesis but how they are established is not well understood. A gradient of the transcription factor Bicoid is known to provide Drosophila embryos with positional information along their anterior-posterior axes. Since Bicoid is enriched in nuclei, nuclei have recently been proposed to act as potential traps or sites of degradation that could slow down Bicoid diffusion from the anterior pole and hence contribute to the observed Bicoid gradient. On p.

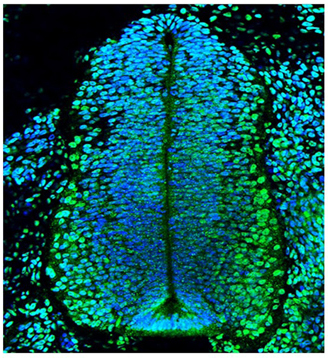

Morphogen gradients provide key positional information during embryogenesis but how they are established is not well understood. A gradient of the transcription factor Bicoid is known to provide Drosophila embryos with positional information along their anterior-posterior axes. Since Bicoid is enriched in nuclei, nuclei have recently been proposed to act as potential traps or sites of degradation that could slow down Bicoid diffusion from the anterior pole and hence contribute to the observed Bicoid gradient. On p.  During spinal cord development, transcription factors and signalling proteins, such as the BMPs, are involved in neural tube (NT) patterning and in inducing neural differentiation. Although epigenetic modifications are known to regulate the expression of key neural development genes in stem cells, whether they have a role in spinal cord development remains unclear. On p.

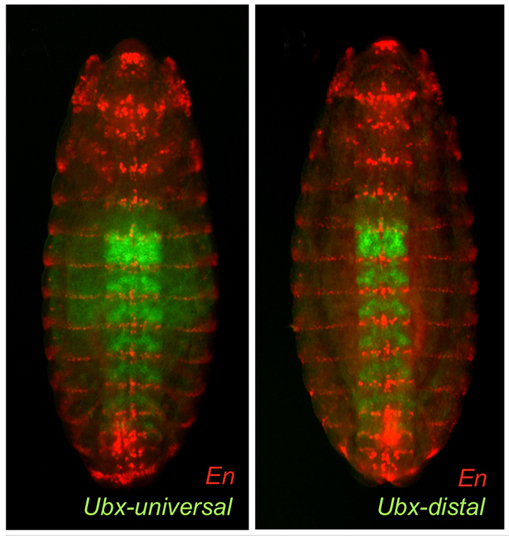

During spinal cord development, transcription factors and signalling proteins, such as the BMPs, are involved in neural tube (NT) patterning and in inducing neural differentiation. Although epigenetic modifications are known to regulate the expression of key neural development genes in stem cells, whether they have a role in spinal cord development remains unclear. On p.  The Hox family of transcriptional regulators plays a central role in specifying segment identity along the anteroposterior axis of animal bodies. The Drosophila Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) is dynamically expressed during development and controls the development of posterior thoracic and anterior abdominal segments. On p.

The Hox family of transcriptional regulators plays a central role in specifying segment identity along the anteroposterior axis of animal bodies. The Drosophila Hox gene Ultrabithorax (Ubx) is dynamically expressed during development and controls the development of posterior thoracic and anterior abdominal segments. On p.  Shoot branching in plants occurs after bud activation in axillary meristems, which are stem cell clusters along the shoot. This process is repressed by strigolactones by a poorly understood mechanism. One model suggests that strigolactones do not act on the bud directly, but inhibit shoot branching by preventing auxin transport out of the bud. Ottoline Leyser and co-workers now show, on p.

Shoot branching in plants occurs after bud activation in axillary meristems, which are stem cell clusters along the shoot. This process is repressed by strigolactones by a poorly understood mechanism. One model suggests that strigolactones do not act on the bud directly, but inhibit shoot branching by preventing auxin transport out of the bud. Ottoline Leyser and co-workers now show, on p.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)