Adult Neurogenesis 2018: Highlights -By Zubair Ahmed Nizamudeen

Posted by Zubair, on 29 June 2018

4WH Neurogenesis: What Where Why When and How?

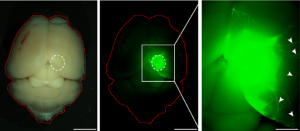

Neurogenesis is understood as the process by which neural stem cells (NSCs) produce new neurons. In the adult mammalian brain, this process is known to persist in two restricted locations- the dentate gyrus (DG) region of the hippocampus (see figure below) and the lateral walls of the subventricular zone (Ming and Song, 2011). Neurogenesis has been reported to occur at a high pace during embryonic development, decrease rapidly during growth and maturity, and persist in the adult brain at very low levels. New born neurons in the mature brain have been affiliated with important functions including learning, memory and damage repair.

Currently, researchers are focused on dissecting the mechanisms of neurogenesis in the adult brain to understand its unique self-repair strategies, which in turn have the potential to combat a variety of challenging neurodegenerative disorders. But do we know enough? Realistically, this is just the start of a new era in regenerative medicine, and the ‘Adult Neurogenesis 2018’ conference had just taken us a couple steps forward by showcasing cutting-edge research progress in this field.

Adult Neurogenesis 2018 was organised by Gerd Kempermann in collaboration with Abcam in the beautiful city of Dresden. The meeting was held in at the Center for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD) (see figure below) which currently hosts eighteen core groups in a network of 87 principal investigators from diverse research institutes on the Dresden campus, with expertise in biomedical fields extending from the biology of cells and tissues to biomaterials to nanoengineering. Gerd welcomed us all and initiated the meeting with a refreshing narrative, briefing us about what history has taught us, where we are headed, and the reason behind the field of adult neurogenesis.

That adult neurogenesis occurs throughout life in mammals including humans has been confirmed by multiple studies and regularly published articles following Joseph Altman and Gopal Das’s original discovery over 50 years ago (Altman and Das, 1965). However, from Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s 90 year old harsh decree of adult brain being devoid of any neurogenesis (Cajal, 1991) to Arturo Alverez-Buylla and colleagues’ 2018 description of undetectable levels of neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus (Sorrells et al., 2018), the field of adult neurogenesis has faced its fair share of obstacles (Kempermann et al., 2018).

There is a growing need not only to unravel the mystery behind adult neurogenesis, but also to develop technology that can provide universal and undeniable proof of its very nature, including its existence and features. Kempermann used these key facts to redefine the impact, importance and purpose of adult neurogenesis.

The Adult Neurogenesis 2018 meeting brought together some of the most influential and inspiring minds in the field of neurogenesis including, but not limited to, F. Gage, S. Jessberger, B. Berninger, S. Thuret, A. Schinder, L. Barry-Cuif, F. Calegari and M. Brand. It hosted a total of 24 talks and showcased 98 posters (see figure below) which allowed researchers from various parts of the world to share and connect with each other.

The meeting provided excellent networking opportunities allowing interdisciplinary collaboration which will ultimately lead to increase in pace and quality of scientific research. Therefore, the very existence of the meeting itself, paved a path towards finding the answer to when and how are we going to able to understand and uncover the potential of adult neurogenesis. In this report, I have managed to highlight some of my personal favourites, which undoubtedly does not cover the entirety of topics covered in the meeting.

Heterogeneity: Similar but not identical

The beauty of adult neurogenesis lies in its complex diversity. Our brain contains different types and subtypes of neuronal and glial cells all with unique functions. Moreover, depending upon factors including temporal intracellular gradients, time of birth, localisation and differences in synaptic connections, cells expressing identical protein markers in the brain can show significantly varied functions. Fortunately, recent discoveries highlighting the in-depth heterogenic nature of the immature cells involved in adult neurogenesis have begun to elucidate some of the most challenging questions regarding complexity.

Vijay Adusumilli highlighted the heterogeneity within nestin expressing NSCs of the hippocampus at a given time. Nestin is a prominent NSC marker in vivo as well in vitro. Interestingly, nestin positive DG NSCs can themselves be split into groups based on their intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) content. His observations emphasised how intricate differences between NSCs can produce functional diversity of neurogenesis in our brain.

Jason Snyder provided us with details on differences and relationships between adult-born and developmentally-born neurons in the hippocampus. Snyder found that changes in adult neurogenesis were inversely proportional to the activity of developmentally-born neurons. He hypothesized that the interplay between adult and developmentally-born neurons plays an important role in the acquisition and turnover of information in the hippocampus.

Alejandro Schinder gave a refreshing introduction to the intricate neuronal connections of granule cells (GCs) in the DG of the hippocampus. His lab had previously demonstrated that immature GCs of DG undergo biased neuronal activation compared to mature neurons (Marín-Burgin et al., 2012), in contrast to other regions of the hippocampus and neocortex. This functional heterogeneity between mature and immature GCs provides insights into their possible role as pattern integrators and differential decoders of information in the DG.

Together, these talks gave us an idea of how heterogeneity within NSCs, and between NSCs and new born neurons, are key factors to consider during future research in translational neuroscience.

Control or to be controlled?

Expanded research in adult neurogenesis has not only helped us provide an unprecedented surveillance of brain development but has also given us a chance to repair brain damage. Since NSCs are known to be the fundamental units of brain regeneration, recent studies have focused on modulating their behaviour and thereby developing possible therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disorders. This meeting was able to showcase some of the important and newly discovered modulators of adult neurogenesis.

-

How is it controlled?

Autophagy is an intracellular degradation system for cytosolic proteins and organelles, which is critical for cellular homeostasis (Nixon, 2013). Iris Schäffner and her colleagues investigated the FoxO family of transcription factors with respect to regulation of autophagy in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Schäffner hypothesized a novel pathway connecting FoxO-dependent autophagic flux to development of adult hippocampal neurons.

Tara Walker talked about how the number of new born DG neurons are kept in check. Regulation of DG neurogenesis involves the death of the majority of new born neurons. She hypothesized that a population of early hippocampal precursor cells die due to ferroptosis, an alternative form of cell death, and thus identified an additional mechanism by which adult hippocampal neurogenesis could be controlled.

Sandra Wendler was able to identify distinct roles of mitochondrial fusion dynamics in the lineage of adult NSCs in the hippocampus. Wendler was able to show that although mitochondrial fusion was dispensable for the proliferative steps of NSCs, this process becomes essential for the maturation and survival of neurons later on.

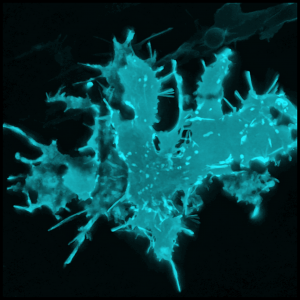

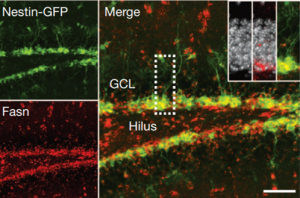

Sebastian Jessberger shared his discoveries on molecular mechanisms underlying neurogenesis with respect to lipid metabolism. He showed that Fasn, a key enzyme in de novo lipogenesis, was highly active in NSCs (see figure below) (Knobloch et al., 2013). His results provided functional coupling between regulation of lipid metabolism and adult NSC proliferation.

Taken together, these talks provided some key examples of how adult neurogenesis is controlled in the brain. A complete picture of the intricate mechanisms underlying neurogenesis are still unknown. However, piece by piece, we have started understanding the secrets of how new born neurons are created and regulated.

-

How can we control it?

Georg Kuhn introduced physical exercise and enriched environment as modulators of adult neurogenesis. Kuhn explained how cardiovascular fitness and exercise are particularly important for prevention, delayed-onset or amelioration of CNS diseases including stroke and dementia (Åberg et al., 2009; Naylor et al., 2008). In parallel, Nora Abrous showed that spatial learning remodels not only new dentate neurons but also creates short term new networks within the hippocampus and long term new networks that extend beyond the hippocampus itself.

Moving deeper in a biological perspective, David Petrik showed how cells regulating adult neurogenesis are responsive to mechanical forces at the tissue level. Increased fluid flow along the walls of the lateral ventricle increased the proliferation of NSCs and this ability was dependent on Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) (Petrik et al., 2018). The flow also controlled calcium oscillations in NSCs on the lateral wall, but not at a deeper niche depth, depicting specific spatial control of neurogenesis by fluid flow.

Federico Calegari took it to the cellular level, exploring whether or not cognitive impairment could be reversed in old age or compensated throughout life by extrinsically exploiting endogenous NSCs. His lab had previously developed a system that allowed temporal control of cdk4–cyclinD1 overexpression to control the number of neurons produced in vivo (Artegiani et al., 2011). This showed, for the first time, that neurogenesis can be controlled in an acute spatio-temporal manner that allowed to elucidate and control adult neurogenesis.

Taken together, these talks provided examples of how control can be imposed upon neurogenesis in the mammalian brain, both extrinsically and intrinsically. Following on, recent studies have started screening for factors that act as master regulators of NSC homeostasis to understand the extent to which we can control neurogenesis.

The truth to be told

The ultimate objective for unfolding the mysteries and unlocking the potential of adult neurogenesis is to provide a better quality of human life. However, due to the restricted localisation and diluted potential of adult neurogenesis in mammals, not to mention to the lack of human subjects, cellular regenerative therapies for the human brain is proceeding at a considerably slow pace. The conference addressed this issue by showcasing novel technological developments and innovative adaptations of pre-existing biomedical tools which can directly increase the speed and quality of discovery with respect to clinical translation.

Studying the properties of neurogenesis can have significant indirect benefits to clinical medicine. Sandrine Thuret talked about how differential neurogenesis can be used as a biomarker to detect the fate of disease pathology in humans. Her lab showed that differential response of NSCs to patient specific serum can be extended to predict conversion of mildly cognitive impaired patients to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Maruszak et al., 2017)

Identification of neurogenic regulators in disease models can serve as key players in restoring healthy physiology in patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Claire Rampon talked about how manipulating mitochondrial properties of new neurons can improve altered cellular properties of an AD mouse brain model and may open new avenues for far-reaching therapeutic strategies for cognitive impairment (Richetin et al., 2017).

Different animal models can have significantly varied neurogenic properties compared to humans which can be particularly useful in developing innovative strategies for human brain repair. Michael Brand talked about how zebrafish is not only an easier model for experimentation, but also provides an excellent source to study adult brain regeneration (Grandel et al., 2006; Kroehne et al., 2011). Brand discussed how zebrafish can be used to study thyroid regulation of adult neurogenesis, emphasising that the genetic factors underlying extensive regeneration in adult zebrafish may be a crucial key to unlock adult brain regeneration in humans.

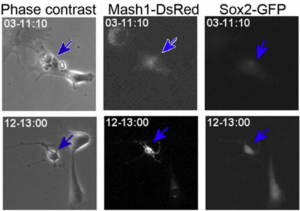

Direct reprogramming of adult cells to neurons is an emerging technology which holds great promise for cell-based brain repair. Benedikt Berninger’s lab had identified resident pericytes (a non-neural cell type in the mature brain) to have the potential to be directly converted into neurons (see figure below) (Karow et al., 2012). Berninger talked about the nature of intermediate states taken up by reprogrammed pericytes towards neurogenesis. He showed that as they reprogram, cells pass through a neural stem cell-like state, and that this state is of functional importance for the reprogramming success (Karow et al., 2018-in press). This knowledge may provide new ways for further improving direct reprogramming and in turn, help overcome the scarcity of neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain.

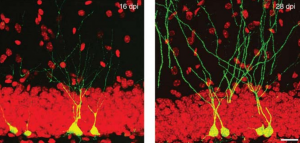

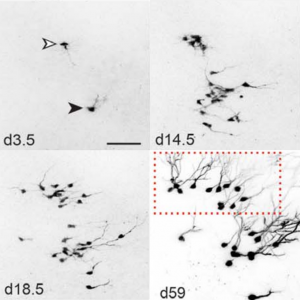

‘Real-time’ or ‘live’ imaging microscopes allow scientists to observe biological functions of cells and tissues in action. Using an intra-vital imaging procedure, Laure Bally-Cuif showed that her lab was able to dynamically image and track a full population of adult NSCs at a single cell resolution within their niche. This provided the power to deduce live aspects of stem cell behaviour over several weeks in vivo (Dray et al., 2015). Jessberger showed how clonal population derived from neurogenic events can be monitored in vivo using 2-photon microscopy (see figure below) (Pilz et al., 2018). He focused on the importance of using technically straightforward measures to study properties of neurogenesis in its native state.

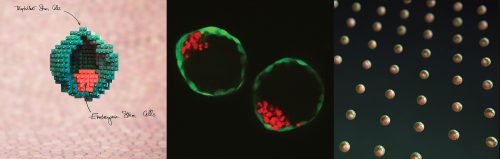

Fred Gage briefed us about our journey through adult neurogenesis, 2-photon microscopical advances and brain organoids. He showed how human brain organoids can be implanted into mice and observed while it integrates into the rodent CNS (see figure below) (Mansour et al., 2018). The motivation was to find a way to vascularize the human organoid to improve the survival and maturation of these 3-Dimensional human brain tissues to better understand human brain development and study human brain disorders.

Taken together, these talks have emphasised how ground-breaking discoveries coupled with the outstanding development in biomedical technologies has allowed remarkable progress in this field, and provided us with a glimpse into the future and promise of adult neurogenesis.

Conclusion

In light of the recent developments in the field of adult neurogenesis, it is an exhilarating era to exist in. The ‘Adult Neurogenesis 2018’ meeting highlighted many inspiring and pioneering discoveries including insights into neurogenic heterogeneity, control of neurogenesis, and recent technological developments. Neurodegenerative disorders are extremely challenging and expensive to treat. The very discovery of neurogenesis to persist adult mammals including humans has filled us with hope. Given the pace of scientific research, the next few decades might just witness a major leap that humanity can take towards clinical neuroscience.

‘’If I were not in this field today, I would have joined after this conference’’-

References

Åberg, M.A.I., Pedersen, N.L., Torén, K., Svartengren, M., Bäckstrand, B., Johnsson, T., Cooper-Kuhn, C.M., Åberg, N.D., Nilsson, M., and Kuhn, H.G. (2009). Cardiovascular fitness is associated with cognition in young adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 20906–20911.

Altman, J., and Das, G.D. (1965). Post-natal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature 207, 953–956.

Artegiani, B., Lindemann, D., and Calegari, F. (2011). Overexpression of cdk4 and cyclinD1 triggers greater expansion of neural stem cells in the adult mouse brain. J. Exp. Med. 208, 937–948.

Cajal, S.R. y (1991). Cajal’s Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System (Oxford University Press).

Dray, N., Bedu, S., Vuillemin, N., Alunni, A., Coolen, M., Krecsmarik, M., Supatto, W., Beaurepaire, E., and Bally-Cuif, L. (2015). Large-scale live imaging of adult neural stem cells in their endogenous niche. Development 142, 3592–3600.

Grandel, H., Kaslin, J., Ganz, J., Wenzel, I., and Brand, M. (2006). Neural stem cells and neurogenesis in the adult zebrafish brain: origin, proliferation dynamics, migration and cell fate. Dev. Biol. 295, 263–277.

Karow, M., Sánchez, R., Schichor, C., Masserdotti, G., Ortega, F., Heinrich, C., Gascón, S., Khan, M.A., Lie, D.C., Dellavalle, A., et al. (2012). Reprogramming of Pericyte-Derived Cells of the Adult Human Brain into Induced Neuronal Cells. Cell Stem Cell 11, 471–476.

Karow, M., Camp, J.G., Falk, S., Gerber, T., Pataskar, A., Gac-Santel, M., Kageyama, J., Brazovskaja, A., Garding, A., Fan, W., et al. (2018). Direct pericyte-to-neuron reprogramming via unfolding of a neural stem cell-like program. Nat Neurosci. Jun 18. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0168-3. [Epub ahead of print]

Kempermann, G., Gage, F.H., Aigner, L., Song, H., Curtis, M.A., Thuret, S., Kuhn, H.G., Jessberger, S., Frankland, P.W., Cameron, H.A., et al. (2018). Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell Stem Cell. April 18. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.004. [Epub ahead of print].

Knobloch, M., Braun, S.M.G., Zurkirchen, L., von Schoultz, C., Zamboni, N., Araúzo-Bravo, M.J., Kovacs, W.J., Karalay, O., Suter, U., Machado, R.A.C., et al. (2013). Metabolic control of adult neural stem cell activity by Fasn-dependent lipogenesis. Nature 493, 226–230.

Kroehne, V., Freudenreich, D., Hans, S., Kaslin, J., and Brand, M. (2011). Regeneration of the adult zebrafish brain from neurogenic radial glia-type progenitors. Development 138, 4831–4841.

Mansour, A.A., Gonçalves, J.T., Bloyd, C.W., Li, H., Fernandes, S., Quang, D., Johnston, S., Parylak, S.L., Jin, X., and Gage, F.H. (2018). An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 432–441.

Marín-Burgin, A., Mongiat, L.A., Pardi, M.B., and Schinder, A.F. (2012). Unique Processing During a Period of High Excitation/Inhibition Balance in Adult-Born Neurons. Science 335, 1238–1242.

Maruszak, A., Murphy, T., Liu, B., Lucia, C. de, Douiri, A., Nevado, A.J., Teunissen, C.E., Visser, P.J., Price, J., Lovestone, S., et al. (2017). Cellular phenotyping of hippocampal progenitors exposed to patient serum predicts conversion to Alzheimer’s Disease. BioRxiv 175604.

Ming, G., and Song, H. (2011). Adult Neurogenesis in the Mammalian Brain: Significant Answers and Significant Questions. Neuron 70, 687–702.

Naylor, A.S., Bull, C., Nilsson, M.K.L., Zhu, C., Björk-Eriksson, T., Eriksson, P.S., Blomgren, K., and Kuhn, H.G. (2008). Voluntary running rescues adult hippocampal neurogenesis after irradiation of the young mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 14632–14637.

Nixon, R.A. (2013). The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 19, 983–997.

Petrik, D., Myoga, M.H., Grade, S., Gerkau, N.J., Pusch, M., Rose, C.R., Grothe, B., and Götz, M. (2018). Epithelial Sodium Channel Regulates Adult Neural Stem Cell Proliferation in a Flow-Dependent Manner. Cell Stem Cell 22, 865-878.e8.

Pilz, G.-A., Bottes, S., Betizeau, M., Jörg, D.J., Carta, S., Simons, B.D., Helmchen, F., and Jessberger, S. (2018). Live imaging of neurogenesis in the adult mouse hippocampus. Science 359, 658–662.

Richetin, K., Moulis, M., Millet, A., Arràzola, M.S., Andraini, T., Hua, J., Davezac, N., Roybon, L., Belenguer, P., Miquel, M.-C., et al. (2017). Amplifying mitochondrial function rescues adult neurogenesis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 102, 113–124.

Sorrells, S.F., Paredes, M.F., Cebrian-Silla, A., Sandoval, K., Qi, D., Kelley, K.W., James, D., Mayer, S., Chang, J., Auguste, K.I., et al. (2018). Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

(3 votes)

(3 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)