I made a conscious choice to switch from dancing to research, and I don’t regret it at all

Posted by the Node, on 2 December 2024

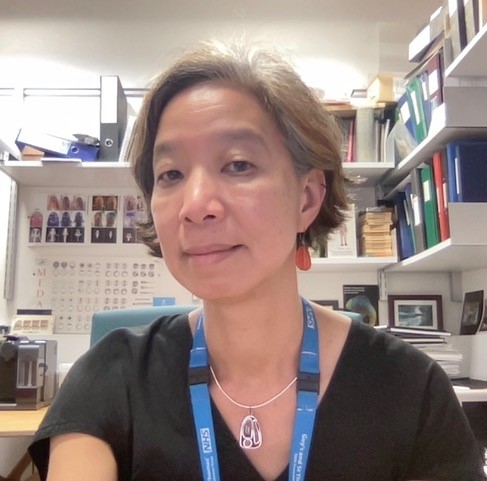

No such thing as a standard career path – an interview with Maria Rostovskaya

Maria Rostovskaya is a senior research scientist at the Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK, studying development using human pluripotent stem cells. Between her undergraduate degree and her PhD, Maria was a dancer and dance teacher for a few years. What made her decide to switch careers and eventually follow an academic career path? How did her experience in dancing shape her subsequent career? We chatted to Maria to find out more.

How has your career path been so far?

I did my undergrad in molecular biology at the Moscow State University. After university, I decided to take a break from the academic career. I became a dance teacher. I also did some lab work during that time, but I did not think of really continuing a career in academia. Then, three years later, I decided to go back to academia and pursue a PhD. I was accepted to the PhD programme at the Max Planck Institute in Dresden. I had two main directions during my PhD – my main project was about bone marrow stem cells and my side project was on human pluripotent stem cells. After my PhD, I continued with a postdoc at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute. Now, I’m a senior scientist at the Babraham Institute at Cambridge, working on human pluripotent stem cells in the context of human development.

After your university degree, you decided to become a dancer and dance teacher. Could you talk us through that decision-making process?

I was curious about many things, and I had always done dancing and science in parallel. During my time at the university, I focused a lot on my studies, so after that, I wanted to expand my other interests. Another reason is, at that time, I was not ready for the transition from studying to doing research. My undergraduate degree involved a lot of theory, and I enjoyed learning about concepts and principles. I think people don’t always realize the difference between learning the theory and doing the research: there is a huge difference in terms of the intellectual load. How we learn from a day spent with textbooks is very different from how we learn from a day working in a lab, and I just wasn’t ready for this difference in dynamics.

How was your experience as a dancer and a dance teacher? What type of dance did you specialize in?

The style of dance is called the Hustle dance. It’s a social dance, and it’s a fusion of salsa, mambo, and west coast swing. It’s a partner dance and can be danced with different music. There is no prepared scheme. It’s a lot about leading, following and improvising with the music. Its uniqueness comes from its freedom and flexibility. You can add various styles and elements. You can style it according to your own feelings.

My dance partner and I also created a unique dance style and fusion. We also designed a teaching course, and we were invited to run workshops in other cities and even abroad. We won several competitions. It was also rewarding to see the achievements and results of my students, because they also won competitions. Some of them went on to become dance teachers. It was a really exciting time, because I had the space for creativity and the opportunity to try various things.

You were enjoying dancing, but then you decided to pursue a PhD. What motivated that decision?

I think I had the feeling that I achieved a lot in dancing, and I thought that I needed to develop further. By that time, I have gained more self-awareness, and I understood what I actually need. For me, it’s important to have opportunities for further development, for professional growth. I like to have a sense of purpose and be intellectually stimulated. With this new-found awareness, I realized that probably I could try going back to academia and pursue a PhD.

How did you approach applying for a PhD and choosing which area you wanted to work in?

At that time, I wasn’t entirely sure that I wanted to go back to academia. I wanted to try, so I chose one PhD programme and applied. I thought if I did not get it, I would just continue with dancing. But I did get it, so I decided to change my career path. It was a real match – it was the right time, the right place, and the right project. I was always excited about molecular biology and cells, and it was a really the right combination of topics for the project.

Was it difficult going back to science after a break?

At that stage, not really, because I was still at the very beginning of a research career. I did not feel very different from everyone else. But because I had already tried another career, I knew a PhD was what I wanted. I think that made the difference for me.

After your PhD, you decided to stay in academia and went to Cambridge to do a postdoc. You’re currently a senior research scientist at the Babraham Institute, UK. What is your research about?

When I came to Cambridge, I was first at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute. Then I made the transition to the Babraham Institute. Now, I use human pluripotent stem cells to model early human development. I study the transcription and epigenetic control of the first lineage decisions. I’m interested in understanding how cells become different at the right time and the right place, and what molecular mechanisms control these decisions. A few years ago, I decided that I also need to add computational skills to my portfolio. There were a lot of big data in my project, and I always had to rely on other people to do the analysis, so I decided to learn bioinformatics. Now in my work, I combine wet lab and computational approaches.

Did being trained as a dancer and teaching dancing help your scientific career? Do you see any parallels in your dancing and scientific experiences?

I think it really shaped my approach to teaching. I do a lot of teaching, and I’ve been teaching for the university for 10 years already. I supervise undergraduate students, and I find a lot of similarities in that respect. I like finding a clear way to explain and structure the knowledge, training skills, identifying key points and filling gaps. I enjoy interacting with my students and I’m very excited seeing them progress. There is definitely a parallel there. Dancing and doing research are also about having a space for creativity, trying out new things, and not being afraid of going to the unknown. Both require being open to something unexpected.

Do you still dance and teach dancing?

I don’t teach dancing anymore, because when I moved to Germany, I had to focus on my PhD. I did not speak German, and I needed to settle in a different country. But I do dance a lot and go to socials events. I often go to festivals or boot camps in different countries. I try to be a part of the dancing community. With the social dance, you don’t need to have a specific partner. You just go and start dancing with any partner.

What’s next for you? Are you planning to continue in academia?

I had another decision point in my career two and a half years ago: my PI left the institute to join a biotech company. By that time, I was already a very senior postdoc and very independent in my research. I knew that I wanted to continue in academia, so I stayed at the Babraham. Throughout my postdoctoral years, I have managed to create my own research niche and approach. I work very independently now, and occasionally I supervise research assistants and summer students. I’m planning to continue the same line of research when I start my own independent group, and I’d like to keep teaching as a part of my career too.

Anything you’ve learned from switching career paths? Looking back, would you have done anything differently?

I certainly learned a lot from this switch. I was not just following the flow of doing a PhD after a science undergraduate degree. I took a break, and I think at that time, that was the right decision at that period of my life. I do not regret at all, not even a second. I don’t know how it would have been otherwise, but if I did not make that decision to take that break and do something else, I wouldn’t have been here now. I gained self-awareness, and it made me value what I have now. Pursuing career in academia is a conscious choice – I have a dream, and I want to follow this dream, and it is worth it. My career switches made me confident that right now, this is the right place for me. But I am open to changes in the future; we don’t know where life brings us.

Do you have any advice to someone thinking of switching career paths?

I would say, have the courage to try. If you feel like you want to try different activities, just give it a go. You will never know unless you try, and perhaps it’s better not to regret about not trying.

You’ve always had dancing and science in your life. But have you ever thought about other career paths?

Maybe a dog walker… I’m just joking. I love dogs, but with an academic career, it’s really hard to have a dog. I already have dancing and science. I think two is a good number!

How do you find time for dancing, despite your busy work schedule?

I think it’s really important to have physical and socializing activities in your life. I think this is why I try to keep dancing in my life as much as I can. It’s about prioritising, organising yourself and getting into a routine. It’s a lot about our mindset and making space for activities outside of work.

Finally, what do you like to do in your spare time?

Well, dancing, of course! I also enjoy winter sports like ice skating and skiing, but the UK is not really the best place to live for these activities. So, to compensate, I take flying lessons. I like progress and I need the space for challenge and creativity. I started flying a few years ago, and so far, I’ve logged about 20 hours of flying. It’s been a bit on and off because flying requires time and focus. When I’m applying for a grant, I take a break from flying, because it’s best not to have the grant application on your mind when you’re flying a plane!

Check out the other interviews in the ‘No such thing as a standard career path’ series.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)