The Secret to Getting the Postdoc You Want

Posted by Marsha Lucas, on 4 February 2014

The following is a re-post of an editorial by Society for Developmental Biology President, Martin Chalfie (Columbia University). It was originally published in the Winter edition of SDB e-news here. For more Society for Developmental Biology news check out SDB e-news – Winter 2014.

I think that one of the scariest parts of being President of the Society for Developmental Biology is coming up with topics for these editorials in the Newsletter.

I think that one of the scariest parts of being President of the Society for Developmental Biology is coming up with topics for these editorials in the Newsletter.

This time, however, I want to write about an issue that has bothered me for many years: how people apply for postdoctoral positions. In my experience most people (around 99%) apply incorrectly for their postdocs, and I suspect that many people do not get the postdoc that they want because of their applications. I’d like to change that situation.

So what do the 99% do that I feel is wrong? These applicants usually send a letter or email (either is fine) saying that they are interested in doing a postdoc and like the research done in the lab. Then they include their CV and the names of three references that can be contacted. Very little thought needs to be put into such applications, and they can be (and probably are) sent to tens if not hundreds of people. I am convinced that the usual reply to such letters is, “Sorry, I don’t have room for anyone else in the lab,” which is really a polite way of saying, “No.”

I think the application should be different, but what I have to suggest requires considerable effort. First, pick two people (or three if you are a masochist) whose work you want to be part of and read their published papers. (At this point you may decide that you not that interested in the research and can stop there.) Second, using the papers and maybe work that you have done for your graduate studies, think about the experiments you want to do. Then, write up these ideas into a two-three-page proposal that you can submit with your application.

Why is a written proposal so important? First, it shows a potential postdoc advisor how you think and what you are interested in. Second, it recognizes that your status as a postdoc is different from that as a graduate student, that you are taking charge of your career. Graduate students are learning how to be scientists; postdocs are colleagues (virtually every practicing scientist you talk to will say that their postdoc was the best part of their career and this is one of the main reasons). Third, it is a document that cannot be ignored. I don’t know anyone that is not impressed that someone outside their lab has thought about their research. (By the way, you can always add to your cover letter that you have based your proposal on published material and that you would be happy to think about other projects that the potential advisor may be working on.) Your ideas will be listened to. Fourth, it means that you are well on your way to having completed an application for funding (another way to show that you are taking charge). Finally (and I have to admit that this reason shows some selfishness on my part), it is your ideas. You may not have said something that your potential sponsor hadn’t thought of, but you came up with the ideas, not him or her. Because they are your ideas (and everyone loves their own ideas), you will work particularly hard to develop them once you are in the lab. Future advisors love this.

In keeping with what I have said about taking charge of your career, I would also add that the line “Here are the names and contact information for three references that can tell you about me,” that appears in most applications should be changed. As it stands the line tells a future employer that he or she needs to do some work. I suggest adding, “I have asked these people to write to you directly. If you do not hear from them in the next two days, please let me know so I can prod them.”

Will this work? I have suggested these steps to all the graduate students in my lab since I was a beginning assistant professor, and virtually every one got the postdoc they wanted. In two cases when graduate students needed to apply to labs in particular cities and happened to choose researchers who were about to move, both of the researchers called me up asking what they needed to do to convince my students to move with them. In one case, the researcher said, “I have never had an application like this,” supporting my contention that few people apply for postdocs this way. I don’t guarantee that following this advice will get you the one postdoc you really want, but I am sure that you will be listened to and in all probability interviewed. Best of luck.

-Marty

(25 votes)

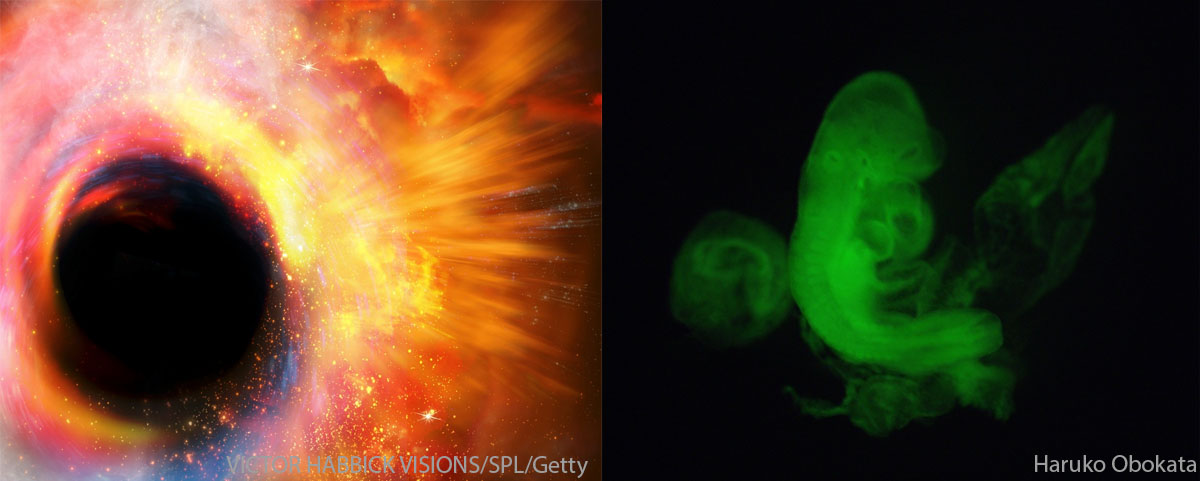

(25 votes) Within the developing neocortex, multiple progenitor cell types contribute to neuronal production, and the properties and relative abundance of these populations help to define the extent of neocortical growth. As well as apically localised radial glial cells (RGCs) that comprise the stem cell compartment, various populations of basal progenitors (BPs) exist – including basal RGCs, with both self-renewal and proliferative capacity, and more restricted progenitors. The stem cell-like properties of RGCs are linked to the fact that these cells are connected to the basal lamina, from which they receive proliferative signals via integrins. Now, Denise Stenzel et al. investigate in rodents the role of integrin αvβ3 in regulating the proliferative capacity of BPs (

Within the developing neocortex, multiple progenitor cell types contribute to neuronal production, and the properties and relative abundance of these populations help to define the extent of neocortical growth. As well as apically localised radial glial cells (RGCs) that comprise the stem cell compartment, various populations of basal progenitors (BPs) exist – including basal RGCs, with both self-renewal and proliferative capacity, and more restricted progenitors. The stem cell-like properties of RGCs are linked to the fact that these cells are connected to the basal lamina, from which they receive proliferative signals via integrins. Now, Denise Stenzel et al. investigate in rodents the role of integrin αvβ3 in regulating the proliferative capacity of BPs ( Langerhans cells (LCs) are antigen-presenting cells of the epidermis, and play a key role in detecting pathogens in the skin and coordinating the immune response. However, the precursors of LCs during embryonic development are poorly characterised, particularly in humans. Here (

Langerhans cells (LCs) are antigen-presenting cells of the epidermis, and play a key role in detecting pathogens in the skin and coordinating the immune response. However, the precursors of LCs during embryonic development are poorly characterised, particularly in humans. Here ( The Drosophila heart provides a relatively simple system for the analysis of gene regulatory networks (GRNs), as it comprises just two cell types – contractile cardial cells (CCs) and non-muscle pericardial cells (PCs). Moreover, many transcription factors (TFs) that regulate Drosophila heart development have been identified and shown to play conserved roles in mammals. On

The Drosophila heart provides a relatively simple system for the analysis of gene regulatory networks (GRNs), as it comprises just two cell types – contractile cardial cells (CCs) and non-muscle pericardial cells (PCs). Moreover, many transcription factors (TFs) that regulate Drosophila heart development have been identified and shown to play conserved roles in mammals. On  The shoot apical meristem (SAM) of higher plants contains the stem cell population that contributes to all above-ground organs. During vegetative growth, leaf primordia emerge from the periphery of the SAM, and the SAM transitions to an inflorescence meristem to initiate the reproductive phase. The WUSCHEL transcription factor specifies stem cell fate, and hence controls the size and activity of the SAM. A gene network involving the CLAVATA signalling pathway, the microRNA miR166g and HD-ZIPIII transcription factors is responsible for regulating WUSCHEL levels. On

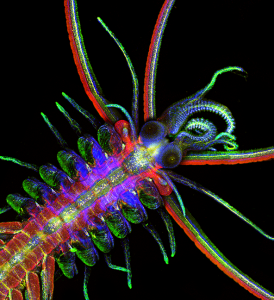

The shoot apical meristem (SAM) of higher plants contains the stem cell population that contributes to all above-ground organs. During vegetative growth, leaf primordia emerge from the periphery of the SAM, and the SAM transitions to an inflorescence meristem to initiate the reproductive phase. The WUSCHEL transcription factor specifies stem cell fate, and hence controls the size and activity of the SAM. A gene network involving the CLAVATA signalling pathway, the microRNA miR166g and HD-ZIPIII transcription factors is responsible for regulating WUSCHEL levels. On  The Drosophila Mcr protein is a member of the thioester protein (TEP) family of proteins, which includes key regulators of innate immunity. Mcr is an unusual member of this family, possessing a putative transmembrane domain and lacking a key residue in the thioester motif. It has, nevertheless, been shown to be involved in phagocytic uptake in cultured Drosophila cells, although its putative immune functions have not been assessed in vivo. Two papers, from Stefan Luschnig and colleagues (

The Drosophila Mcr protein is a member of the thioester protein (TEP) family of proteins, which includes key regulators of innate immunity. Mcr is an unusual member of this family, possessing a putative transmembrane domain and lacking a key residue in the thioester motif. It has, nevertheless, been shown to be involved in phagocytic uptake in cultured Drosophila cells, although its putative immune functions have not been assessed in vivo. Two papers, from Stefan Luschnig and colleagues ( Both studies identify lethal EMS mutations inMcr in independent genetic screens, finding mutant phenotypes typical of SJ components. Consistent with a putative role in SJ formation, the protein colocalises with other SJ proteins at the lateral membrane. They further find that Mcr localisation is dependent on core SJ components and that, conversely, SJ proteins are mislocalised in Mcr mutants. At the morphological and ultrastructural level, SJs are disrupted in the absence of Mcr, and functional assays demonstrate that Mcr is required to form an effective paracellular barrier. As well as identifying a new SJ protein essential for barrier integrity, these two studies suggest an intriguing link between SJs and innate immunity. The epithelial barrier represents the first line of defence against pathogen invasion, andDrosophila haemocytes are known to undergo an epithelialisation-like process when encapsulating pathogens in the haemolymph. The identification of Mcr as a protein involved in both SJ formation and innate immunity now provides a molecular connection, and opens up new avenues for investigating potential functional links, between these two seemingly disparate processes.

Both studies identify lethal EMS mutations inMcr in independent genetic screens, finding mutant phenotypes typical of SJ components. Consistent with a putative role in SJ formation, the protein colocalises with other SJ proteins at the lateral membrane. They further find that Mcr localisation is dependent on core SJ components and that, conversely, SJ proteins are mislocalised in Mcr mutants. At the morphological and ultrastructural level, SJs are disrupted in the absence of Mcr, and functional assays demonstrate that Mcr is required to form an effective paracellular barrier. As well as identifying a new SJ protein essential for barrier integrity, these two studies suggest an intriguing link between SJs and innate immunity. The epithelial barrier represents the first line of defence against pathogen invasion, andDrosophila haemocytes are known to undergo an epithelialisation-like process when encapsulating pathogens in the haemolymph. The identification of Mcr as a protein involved in both SJ formation and innate immunity now provides a molecular connection, and opens up new avenues for investigating potential functional links, between these two seemingly disparate processes. Pax genes encode a family of transcription factors that orchestrate complex processes of lineage determination in the developing embryo. Here, Judith Blake and Melanie Ziman review the molecular functions of Pax genes during development and detail the regulatory mechanisms by which they specify and maintain progenitor cells across various tissue lineages. See the Primer article on p.

Pax genes encode a family of transcription factors that orchestrate complex processes of lineage determination in the developing embryo. Here, Judith Blake and Melanie Ziman review the molecular functions of Pax genes during development and detail the regulatory mechanisms by which they specify and maintain progenitor cells across various tissue lineages. See the Primer article on p.  James Wells and Jason Spence review how recent advances in developmental and stem cell biology have made it possible to generate complex, three-dimensional, human intestinal tissues in vitro through directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. See the Primer on p.

James Wells and Jason Spence review how recent advances in developmental and stem cell biology have made it possible to generate complex, three-dimensional, human intestinal tissues in vitro through directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. See the Primer on p.  (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(7 votes)

(7 votes)