A day in the life of an Ascidian Lab

Posted by Alicia Madgwick and Marion Gueroult-Bellone, on 10 February 2014

Dear The Node readers,

We are Alicia (1st year PhD student) and Marion (3rd year PhD student) and we work in an ascidian lab at CNRS, Montpellier in France. Alicia’s aim is to compare gene regulatory networks of Ciona intestinalis and Phallusia mammillata during early embryogenesis. Ciona is much better characterised, therefore, Alicia has so far only worked with Phallusia. Marion works on enhancers and aims to better understand the sequence determinants of their activity, using Ciona intestinalis as a model organism.

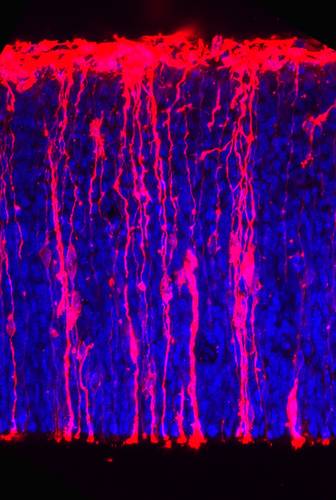

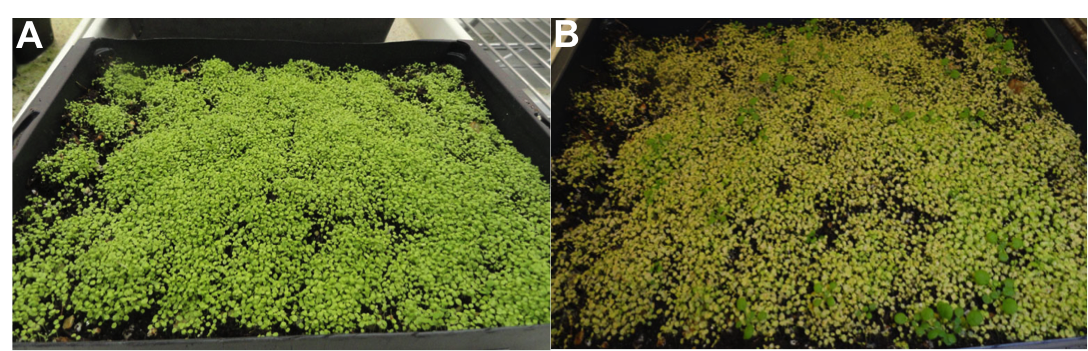

Phallusia mammillata in a jazzy setting: they are a brilliant model organism to study developmental biology. Unfortunately, we no longer have the blue backdrop for our tanks but we do have a starfish!

Working with ascidians

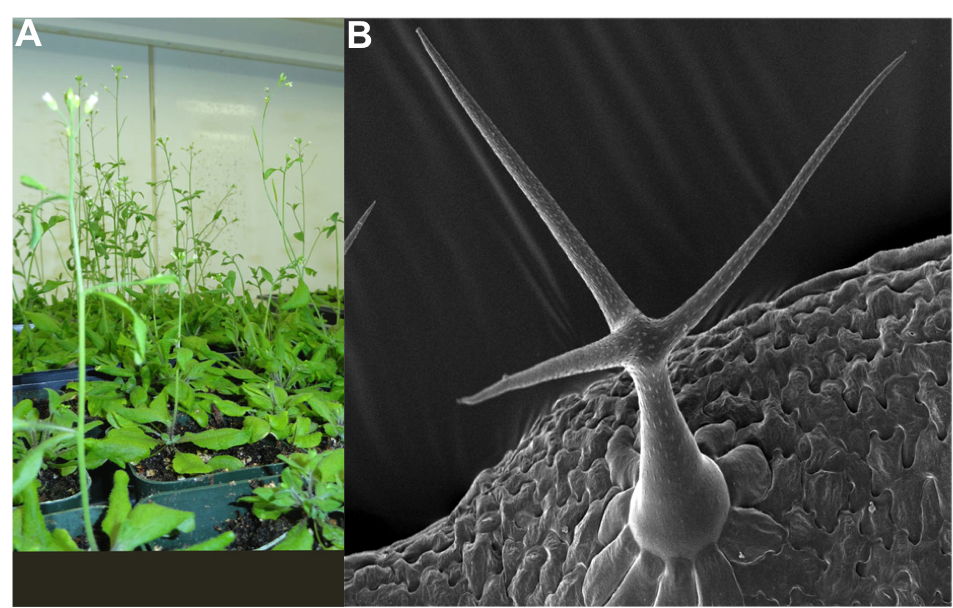

In the world, more than 70 labs work with ascidians[1]. Ascidians belong to the tunicate group; these are marine invertebrates that belong to the phylum Chordata. Tunicates are the sister group of vertebrates with whom they share some features of chordate embryonic developmental programme such as the formation of tadpole larvae. Due to their small and rapidly evolving genome, they are powerful organisms to study chordate evolution. Ascidians are simple genetically because they have not undergone whole genome duplication events and exhibit limited gene redundancy and compact regulatory regions.

The sea squirt Ciona intestinalis is a good model to study developmental biology; they have rapid development and the embryos have invariant lineages. Specialised databases such as Aniseed[2], which was created by the Lemaire lab, have catalogued an atlas of expression profiles, cell lineages and single cell morphological properties and also gene, transcript and protein data. One can retrieve information about each cell in the embryo through different identification markers (name, position), which facilitates the analysis and interpretation of results.

Phallusia mammillata and Ciona intestinalis are thought to have diverged about 300 million years ago but they still share a common invariant embryonic cell lineage. Phallusia arrived in our lab ~3 years ago because of its experimental advantages over Ciona: they have more eggs, transparent embryos and show much less seasonality in embryo production. After a few optimisations, we can now perform all of Ciona’s routine experiments on Phallusia. Comparative genomics approaches can be undertaken to study ascidian developmental programs as many ascidian genomes have now been sequenced.

Ascidians are simple organisms making them easy to analyse. They have a much lower cell number during embryogenesis when compared to vertebrates: 110 to 112 at the onset of gastrulation and about 2600 cells at the tadpole stage. Due to their invariant cell lineage, a phenotype can be characterised with single cell resolution. Electroporation provides a strong tool to easily and quickly make hundreds of transgenic embryos making ascidians a powerful model to study gene regulation.

No Ciona were harmed in the making of this video – our colleague Mathieu playing around with their siphons.

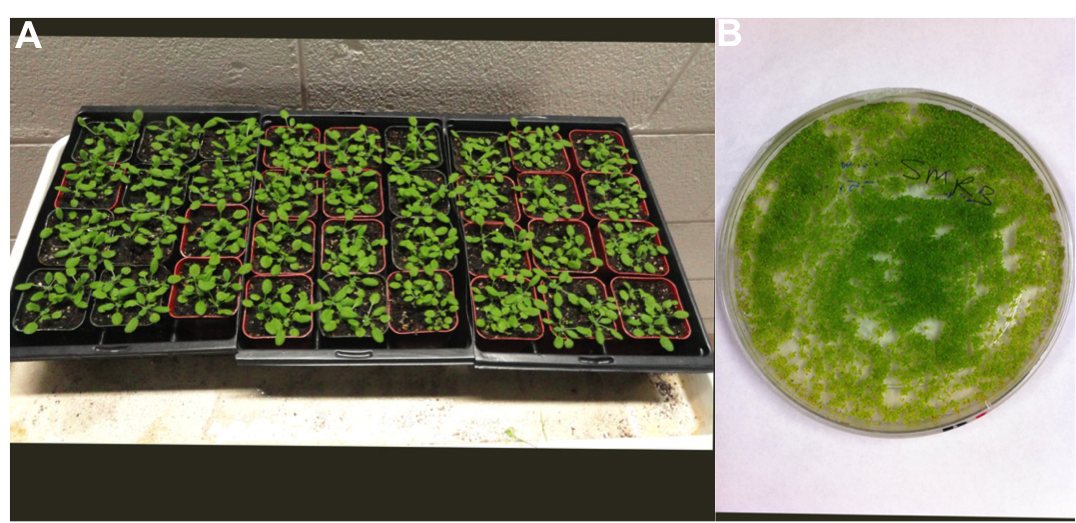

The routine in the lab

One of our favourite practicals is collecting the eggs and sperm from our dear Phallusia; this is done first thing in the morning in our 17°C embryo room. It is always exciting to see the volume of eggs that we manage to collect; it is cause for celebration when the Phallusia has 1.5ml or more. Sperm is not quite as exciting as we only require 10µl; nevertheless, it is still much appreciated.

Dechorionation is performed to remove the chorion and follicular cells which allows a better visualization of the embryonic development and facilitates any further experiments. Phallusia dechorionation lasts a couple of hours. In Ciona, this process is very fast and it is performed after fertilisation. Eggs are now very fragile and should be gently manipulated. Fertilisation is rather fast: sperm is activated (under the stereoscope, we can see the sperm become agitated), and then mixed with eggs. Most of the eggs are fertilized at the same time and thousands of embryos will develop in a synchronous way. From this point on, 20 minutes remain before the first cleavage. During this short time frame, electroporations can be performed.

Collecting our embryos at each stage is a day-long process; it takes the embryos up to 5 hours to reach early gastrula. We try to disperse the embryos as much as possible in the plates as they develop to avoid that they touch and fuse together to create what we call little monsters. Once they have reached the stage of interest, we fix the embryos and colour them if needed. From here on, our embryos can be kept for many months.

Microinjection is a very common technique in ascidian laboratories. It is used for 2 main goals: exogenous expression (microinjection of mRNA) and gene expression knock down (microinjection of morpholinos). Ascidian oocytes are particularly sensitive to microinjection when compared to other species and easily explode or get stuck to the material during microinjection until you get the technique right (we are lucky to have our post-doc Ulla). It is a rather slow technique demanding a high degree of patience and precision but its potential is fantastic. Unlike electroporation, microinjection allows for ubiquitous expression without mosaicism. You can also use interesting control situations with a single embryo. Microinjection of mRNA in a single cell at the 2 cell-stage allows to have half of an embryo expressing an exogenous mRNA whilst the other half remains wild type. Ascidians have bilateral symmetry until late embryonic stages. Although in terms of analysis microinjection techniques are very appealing they provide a much lower number of transgenics to work with than electroporation techniques.

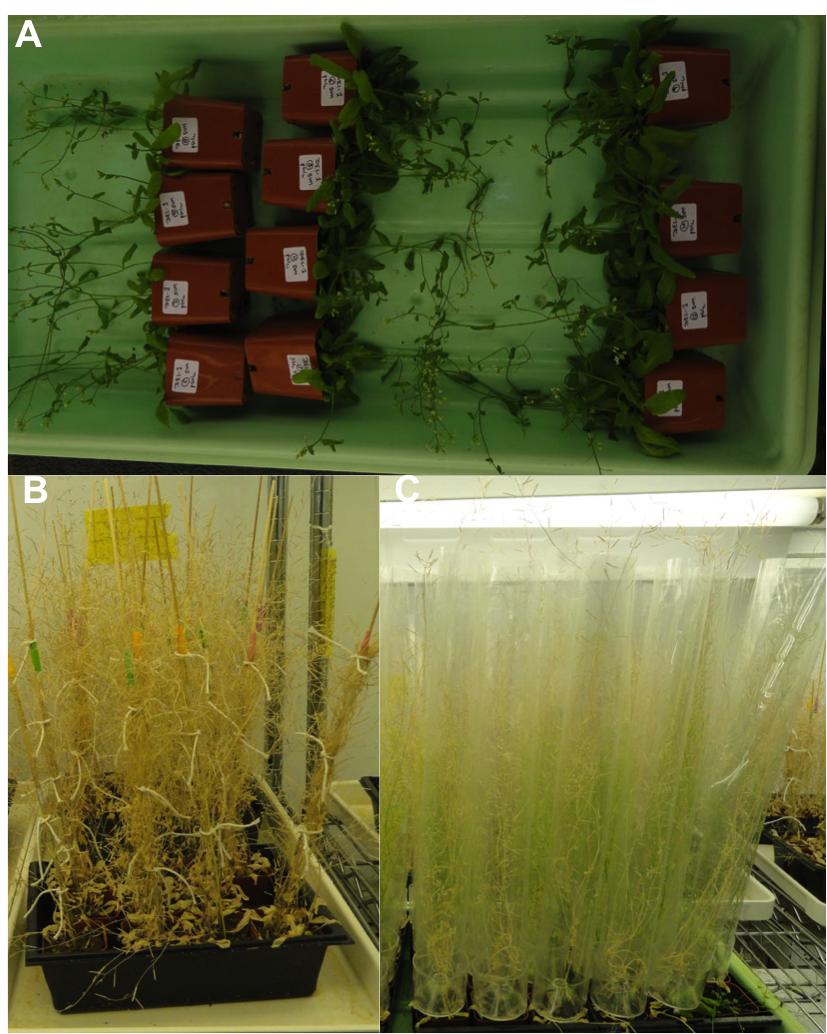

Our ascidian tanks – a main attraction within our building where many come to admire our animals.

Shipment and animal care

We get a weekly shipment of Phallusia and Ciona. Before they are transferred to the tanks, the tanks are thoroughly cleaned during which time the animals are kept in the water in which they were transported. This waiting period means that their water temperature can gradually warm up to match the temperature of the tank water. We do not want to disturb the animals by transferring them before they are ready. We have to order each shipment a week in advance because a special boat and diving expeditions are organised to collect the animals by Roscoff Marine station. We thus need to plan ahead how many animals we need and order only what is required.

Our tanks are in the lab where we work so we regularly check how our animals are doing. To assess if the animals are healthy, we give the tanks a little tap to see if the animals respond by closing their siphons. The colour (and the smell) of the animals can also be an indicator of their health as they turn darker when they die. We have to remove dead animals as soon as possible because they raise nitrite levels in the tanks, which is bad for the other animals. Our sea squirts are kept in natural sea water which is delivered by an oyster farmer.

Working with wild animals

We have not yet started to culture ascidians in our lab; therefore, we work with wild animals delivered from Brittany. Ciona’s fertility depends greatly on sea water temperatures; the period during which they produce eggs spans from April to November in France. So we have to take this into account when planning our experimental work. Funnily enough, our experiments greatly depend on the climatic conditions 1000km from our lab! At each delivery, we could be in for a surprise: did our animals survive the trip? Do they have eggs? Will they develop properly? One pleasant surprise we occasionally get is clandestine animals attached to the Phallusia such as starfish, brittle stars, urchins, worms, annelids or porcelains and the list goes on. At the moment, we have a beautiful purple starfish as a lab pet and we feed her mussels.

Acknowledgments – We would like to thank our postdoc Ulla-Maj Fiuza for her time helping us write this article (and for her microinjection knowledge).

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(8 votes)

(8 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)