A Perfect Lab Leaving List

Posted by Natalie Butterfield, on 4 December 2013

Say goodbye to the lab books. They may let you keep it. But usually, sadly, it must stay. Despite being illegible to anyone but you, and never mind the amusing cartoons. The best you can do is a photocopy. If like me you favour the ‘pop-up lab book’ approach to data recording, the job may look slightly daunting. Personally, my lab book is a three dimensional work of art. A photocopy is just not going to convey the essence of my meaning. Yet for many of us, the urge to copy large tracts of our lab books is irresistible.

Remove all those personal touches you took years to accumulate around you. You know the ones. We all have them. For example, I have in front of me right now:

A rainbow stress ball in the shape of a brain. Courtesy of some trade display, company long since forgotten

Ditto a rubber duck wearing a lab coat.

An amusing picture of a lemur that was sent to me during my Ph.D. and is now somewhat of a mascot

One of those fluffy microbes that got popular a while back that you could give to people and joke about gifting them with mono or Ebola. This one is a rather adorable fat cell.

Countless post-it notes with essential information nuggets such as passwords, chemical formulae, how to skip blank cells in Microsoft Excel and a choice selection of French vocabulary

Unbelievably, your successor is unlikely to treasure these as you have, so you may choose to bequeath them to the like-minded souls around you, or give them a one-way trip into the bin on top of the lab book copies.

Get rid of all your solutions. There is nothing more lonely than a collection of old buffers. Here’s a sad fact: no one really trusts your buffer. It’s a personal thing, this is my buffer, I made it, and in it I trust, even though I know you made your buffer exactly the same way and you look reasonably clean. But I’ve seen that amusing bit of fungal fluff you found in your media bottle that you’ve been nurturing on your shelf to see how big it gets and it’s nothing personal, but I’m going to make my own buffer. Incidentally, now is the time to also get rid of any of your own fungal media pets.

Vintage journal articles. Is it just me or does reading other people’s article copies feel weird? Pre-loved literature (scribbled notes are the worst), makes me terribly uncomfortable, to the extent that, shamefully, I will print another copy rather than read someone else’s vintage papers. At this point it may be kindest to consign the whole pile to the recycling bin and think seriously about planting some trees.

Wipe your hard drive. Copy your data, purge your personal stuff and make sure that novel you’ve been writing during ten minute incubations is safely out of the way. Because someone is going to inherit your computer and unless you want to give them a unprecedented window into your life via your old emails, it’s time to search and destroy.

Fridge stocks. Sadly, they will either go off or grow stuff. Possible exceptions are pricy or rare things like antibodies which you should put back where you found them immediately (see next point).

Freezer stocks. Are you the one who took the second last tube of that reagent from the communal box that time you were working really late at night and forgot to put it back? We’ve all been there. It’s time for us to do the walk of shame back to the freezer with all the expensive things we’ve been hoarding. Best done last thing with as few witnesses as possible.

Now walk over to the minus 80C freezer. That cold, frozen wasteland of very important and largely forgotten samples. Samples labelled 1-10, or something similarly inscrutable that doesn’t even make sense to you anymore since the day you tucked them down the side of a box rather than safely inside it because it was only going to be in there for a couple of days. It’s time to let go and move on to…

Liquid nitrogen stocks. The pinnacle of storage paranoia. Exercise some caution here (not just for the very real possibility of frostbite). Things in here are most likely expensive and temperamental and very, very useful. Often best to walk away quietly.

All the rest of your various samples that someone might use someday. If you don’t care for your name being taken in vain throughout the ages, it’s nice to treat your tubes to a label. With a date. And perhaps even a lab book reference. When it comes to your samples, is there any such thing as Too Much Information?

So you’ve cleaned out your desk, your fridge is empty, and apart from the frostbite, you’re in good shape. You may be slightly hung-over from the leaving party, and you’ve definitely got a giant novelty goodbye card. Congratulations, you’re the perfect leaver.

(12 votes)

(12 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Terminally differentiated cells are generally considered to be in a developmentally locked state in vivo; they are incapable of being directly reprogrammed into an entirely different state. Now, on

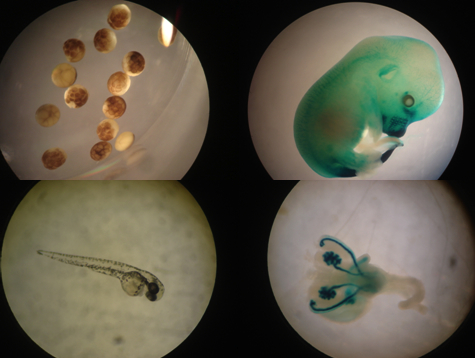

Terminally differentiated cells are generally considered to be in a developmentally locked state in vivo; they are incapable of being directly reprogrammed into an entirely different state. Now, on  Zebrafish have a remarkable capacity to regenerate and, as such, are being used increasingly to study stem cells and organ regeneration. Here, Chen-Hui Chen, Kenneth Poss and colleagues establish a luciferase-based approach for visualising stem cells and regeneration in adult zebrafish (

Zebrafish have a remarkable capacity to regenerate and, as such, are being used increasingly to study stem cells and organ regeneration. Here, Chen-Hui Chen, Kenneth Poss and colleagues establish a luciferase-based approach for visualising stem cells and regeneration in adult zebrafish ( Wnt signalling plays important roles during embryonic patterning and in tissue homeostasis, and mutations that affect the Wnt pathway are associated with cancer. Despite this, the exact way in which the Wnt pathway is regulated is still not fully understood. Now, Amy Bejsovec and colleagues uncover a novel regulator of Wnt signalling (

Wnt signalling plays important roles during embryonic patterning and in tissue homeostasis, and mutations that affect the Wnt pathway are associated with cancer. Despite this, the exact way in which the Wnt pathway is regulated is still not fully understood. Now, Amy Bejsovec and colleagues uncover a novel regulator of Wnt signalling ( The hair follicle epithelium forms a tube-like structure that is continuous with the epidermis, but how the lumen of this structure is created during morphogenesis and regeneration remains unclear. Now, Sunny Wong and colleagues identify a novel population of cells that initiates hair follicle lumen formation in mice (

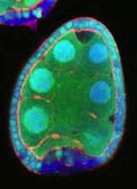

The hair follicle epithelium forms a tube-like structure that is continuous with the epidermis, but how the lumen of this structure is created during morphogenesis and regeneration remains unclear. Now, Sunny Wong and colleagues identify a novel population of cells that initiates hair follicle lumen formation in mice ( The pituitary gland is an endocrine organ that plays a role in various physiological processes, including growth, metabolism and reproduction. The development of various pituitary endocrine cells is influenced by a number of transcription factors and signals. In this issue (

The pituitary gland is an endocrine organ that plays a role in various physiological processes, including growth, metabolism and reproduction. The development of various pituitary endocrine cells is influenced by a number of transcription factors and signals. In this issue ( The neural crest (NC) is a transient structure that gives rise to multiple lineages. Despite intense studies, it is still unclear whether the NC represents a homogeneous population of cells. Here, Jean Paul Thiery and colleagues examine this issue (

The neural crest (NC) is a transient structure that gives rise to multiple lineages. Despite intense studies, it is still unclear whether the NC represents a homogeneous population of cells. Here, Jean Paul Thiery and colleagues examine this issue ( Many organisms and their constituent tissues and organs vary substantially in size but differ little in morphology; they appear to be scaled versions of a common template or pattern. Here, David Umulis and Hans Othmer investigate the underlying principles needed for understanding the mechanisms that can produce scale invariance in spatial pattern formation and discuss examples of systems that scale during development. See the Review article on p.

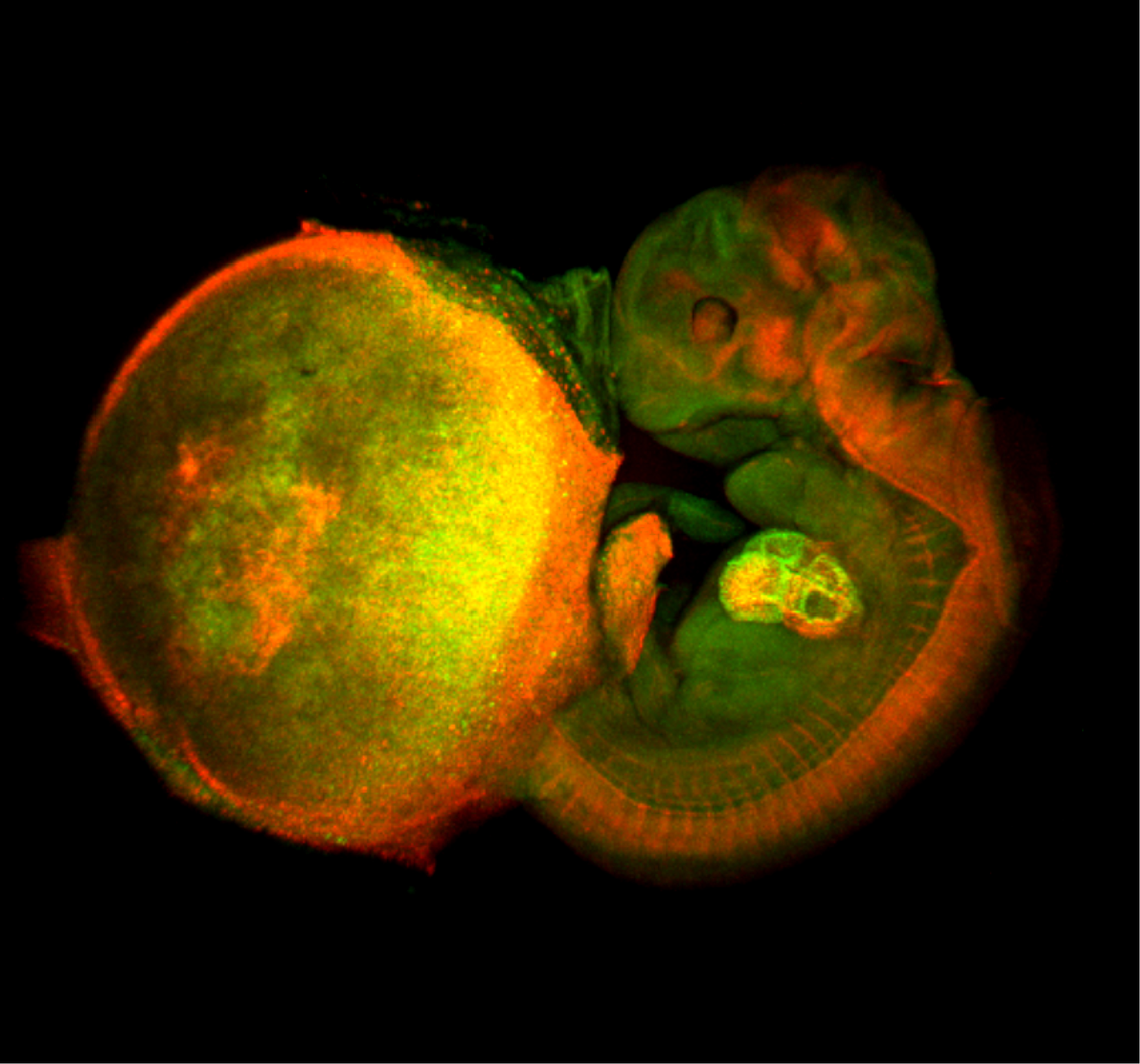

Many organisms and their constituent tissues and organs vary substantially in size but differ little in morphology; they appear to be scaled versions of a common template or pattern. Here, David Umulis and Hans Othmer investigate the underlying principles needed for understanding the mechanisms that can produce scale invariance in spatial pattern formation and discuss examples of systems that scale during development. See the Review article on p.  How can the revolution in our understanding of embryonic development and stem cells be conveyed to the general public? Here, Ben-Zion Shilo presents a photographic approach to highlight scientific concepts of pattern formation using metaphors from daily life, displaying pairs of images of embryonic development and the corresponding human analogy. See the Spotlight article on p.

How can the revolution in our understanding of embryonic development and stem cells be conveyed to the general public? Here, Ben-Zion Shilo presents a photographic approach to highlight scientific concepts of pattern formation using metaphors from daily life, displaying pairs of images of embryonic development and the corresponding human analogy. See the Spotlight article on p.

– Atsushi Miyawaki and colleagues wrote about their recent paper in Development using

– Atsushi Miyawaki and colleagues wrote about their recent paper in Development using