In Development this week (Vol. 141, Issue 1)

Posted by Seema Grewal, on 17 December 2013

Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

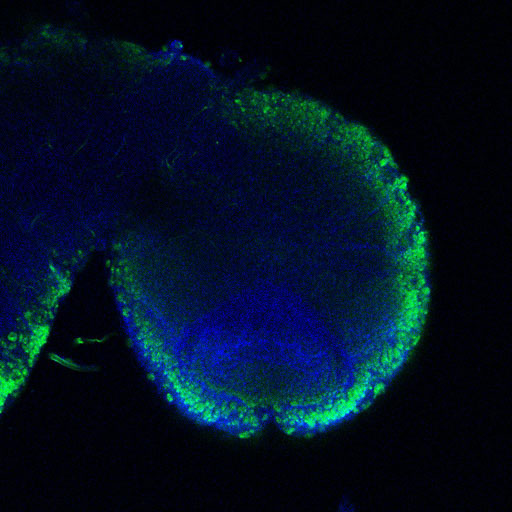

GABAB inhibits neural stem cell proliferation

Neurotransmitter functions are typically associated with neural function rather than with development, but there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that neurotransmitters may also regulate cell proliferation and differentiation in the nervous system. Recent work has demonstrated that GABAA receptor signalling can control adult neurogenesis in the mouse. Verdon Taylor and co-workers now investigate a role for GABAB receptors in the adult mouse hippocampus (p. 83), finding that deletion or inhibition of GABAB1 promotes proliferation of neural stem cells (NSCs), whereas GABAB-receptor agonists induce NSC quiescence. These effects of manipulating GABA signalling appear to represent a cell-autonomous function for GABAB receptors in NSCs. The authors propose that GABAB may be part of a crosstalk mechanism between differentiated neurons and the progenitor population, such that neurogenesis is appropriately coordinated with neural activity. While it has yet to be determined how GABA signalling regulates NSC fate, it is increasingly clear that neurotransmitter-mediated signalling in NSCs is an important mechanism by which neurogenesis can be regulated.

Neurotransmitter functions are typically associated with neural function rather than with development, but there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that neurotransmitters may also regulate cell proliferation and differentiation in the nervous system. Recent work has demonstrated that GABAA receptor signalling can control adult neurogenesis in the mouse. Verdon Taylor and co-workers now investigate a role for GABAB receptors in the adult mouse hippocampus (p. 83), finding that deletion or inhibition of GABAB1 promotes proliferation of neural stem cells (NSCs), whereas GABAB-receptor agonists induce NSC quiescence. These effects of manipulating GABA signalling appear to represent a cell-autonomous function for GABAB receptors in NSCs. The authors propose that GABAB may be part of a crosstalk mechanism between differentiated neurons and the progenitor population, such that neurogenesis is appropriately coordinated with neural activity. While it has yet to be determined how GABA signalling regulates NSC fate, it is increasingly clear that neurotransmitter-mediated signalling in NSCs is an important mechanism by which neurogenesis can be regulated.

Tracking the causes of age-related aneuploidy

Chromosome mis-segregation during meiosis leads to aneuploidy, and hence to reduced fertility and birth defects. The frequency of aneuploidy increases in older mothers. Various mechanisms have been proposed to account for this correlation between maternal age and chromosome segregation defects, most placing the emphasis on errors occurring in meiosis I (MI). Keith Jones and colleagues (p. 199) now use sophisticated live imaging of young and aged mouse oocytes to follow individual bivalents through MI to metaphase II (metII) arrest. In aged oocytes, they observe defects in MI such as weakly attached bivalents and lagging chromosomes during anaphase, but surprisingly find no significant defects in chromosome congression or bivalent segregation. Instead, their data suggest that aneuploidy in aged oocytes is primarily a result of premature separation of dyads during meiosis II, likely during assembly of the metII spindle. The authors propose that these errors are a result of cohesion loss during MI, but – in contrast to previous proposals – that the major segregation errors only occur during meiosis II.

Chromosome mis-segregation during meiosis leads to aneuploidy, and hence to reduced fertility and birth defects. The frequency of aneuploidy increases in older mothers. Various mechanisms have been proposed to account for this correlation between maternal age and chromosome segregation defects, most placing the emphasis on errors occurring in meiosis I (MI). Keith Jones and colleagues (p. 199) now use sophisticated live imaging of young and aged mouse oocytes to follow individual bivalents through MI to metaphase II (metII) arrest. In aged oocytes, they observe defects in MI such as weakly attached bivalents and lagging chromosomes during anaphase, but surprisingly find no significant defects in chromosome congression or bivalent segregation. Instead, their data suggest that aneuploidy in aged oocytes is primarily a result of premature separation of dyads during meiosis II, likely during assembly of the metII spindle. The authors propose that these errors are a result of cohesion loss during MI, but – in contrast to previous proposals – that the major segregation errors only occur during meiosis II.

Why timing matters during segmentation

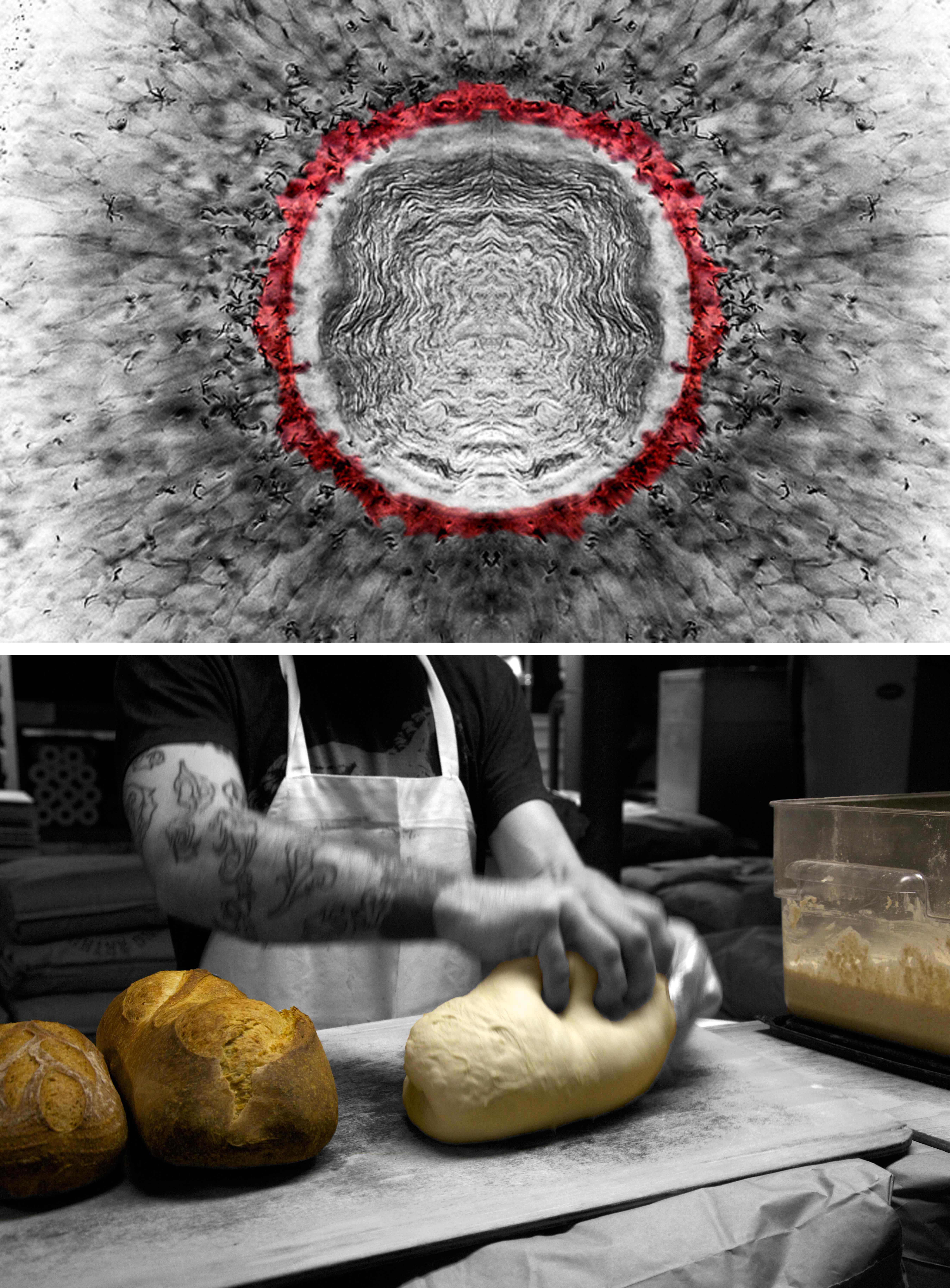

Vertebrate somites form via a sequential process of segmentation, which proceeds from anterior to posterior. In many species, anterior somites form more quickly than posterior ones, but whether this is functionally important, and how the switch in timing might be controlled, is unknown. Now (p. 158), Takaaki Matsui and co-workers address these issues in zebrafish, where the anterior four somites form every 20 minutes, while more posterior ones form every 30 minutes. They find that this difference in timing is not due to a change in how long a somite takes to form, but rather to the extent of overlap between segmentation periods. Mechanistically, retinoic acid signalling appears to be key to regulating the transition from fast-forming to slow-forming somites, acting via Ripply1 to regulate the clock gene her1. When RA signalling is impaired, there is a specific vertebral defect at the head-to-trunk linkage, indicating the functional importance of this anterior-posterior difference in the rate of somitogenesis.

Vertebrate somites form via a sequential process of segmentation, which proceeds from anterior to posterior. In many species, anterior somites form more quickly than posterior ones, but whether this is functionally important, and how the switch in timing might be controlled, is unknown. Now (p. 158), Takaaki Matsui and co-workers address these issues in zebrafish, where the anterior four somites form every 20 minutes, while more posterior ones form every 30 minutes. They find that this difference in timing is not due to a change in how long a somite takes to form, but rather to the extent of overlap between segmentation periods. Mechanistically, retinoic acid signalling appears to be key to regulating the transition from fast-forming to slow-forming somites, acting via Ripply1 to regulate the clock gene her1. When RA signalling is impaired, there is a specific vertebral defect at the head-to-trunk linkage, indicating the functional importance of this anterior-posterior difference in the rate of somitogenesis.Controlling expression by nuclear position

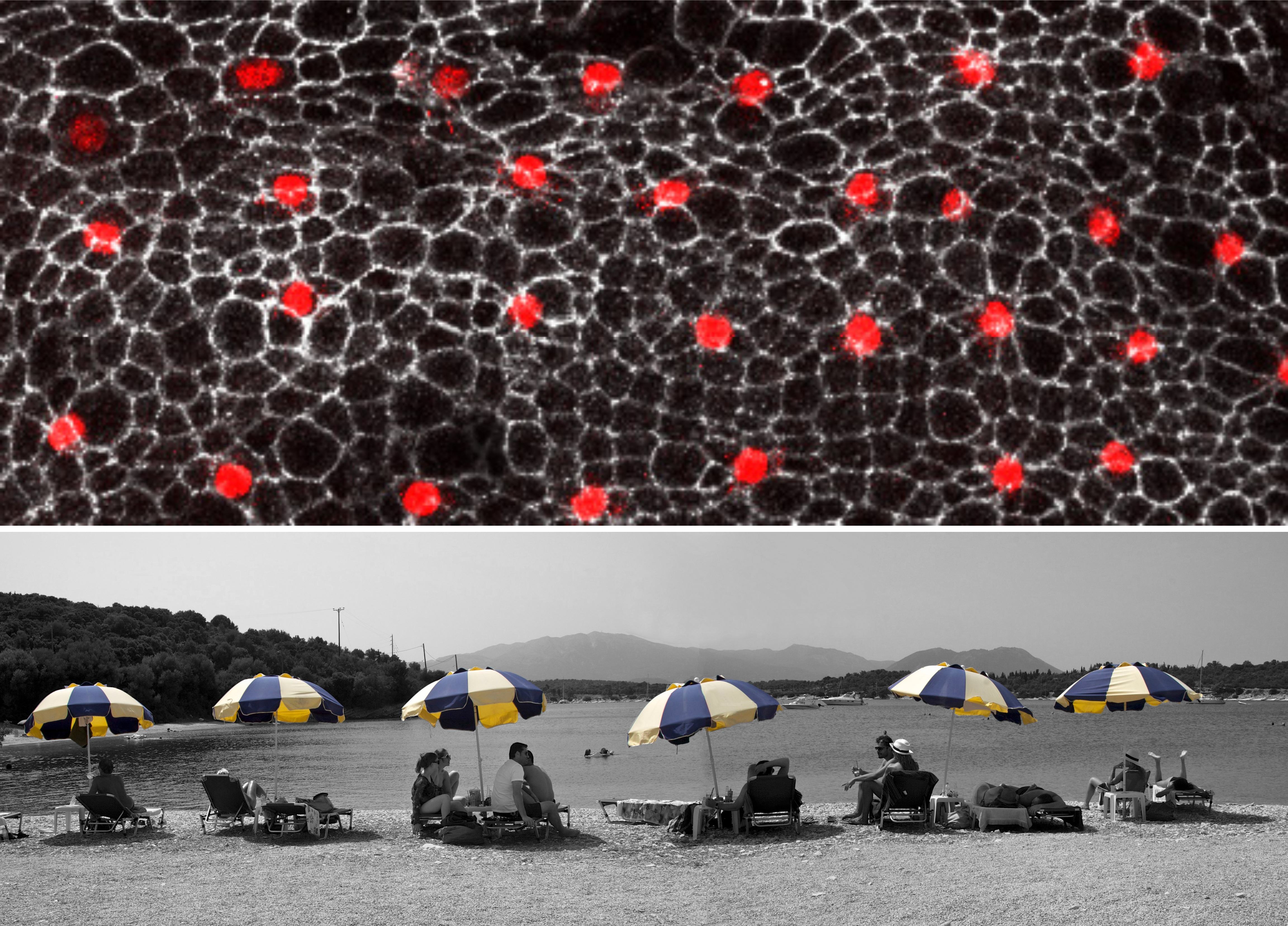

Within the nucleus, active gene loci tend to cluster together in the nuclear interior, while inactive genes are often found at the nuclear lamina. On p. 101, Vladimir Botchkarev, Michael Fessing and co-workers find that developmentally regulated gene expression from the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) – a locus containing genes associated with epidermal barrier formation – is associated with changes in nuclear position. At early stages of mouse development, the EDC is silent and is located at the periphery, but it moves more centrally prior to gene activation and becomes associated with SC35 nuclear speckles – an indication of transcriptional activity. This relocation is dependent on the epidermal transcription factor p63. Moreover, the authors find that p63 directly regulates the expression of the chromatin remodeller Brg1, and that Brg1 is required for the relocation and activation of the EDC. These results underscore the importance of higher order chromatin structure for the regulation of gene expression, and identify a mechanism by which this nuclear organisation can be developmentally regulated.

Within the nucleus, active gene loci tend to cluster together in the nuclear interior, while inactive genes are often found at the nuclear lamina. On p. 101, Vladimir Botchkarev, Michael Fessing and co-workers find that developmentally regulated gene expression from the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) – a locus containing genes associated with epidermal barrier formation – is associated with changes in nuclear position. At early stages of mouse development, the EDC is silent and is located at the periphery, but it moves more centrally prior to gene activation and becomes associated with SC35 nuclear speckles – an indication of transcriptional activity. This relocation is dependent on the epidermal transcription factor p63. Moreover, the authors find that p63 directly regulates the expression of the chromatin remodeller Brg1, and that Brg1 is required for the relocation and activation of the EDC. These results underscore the importance of higher order chromatin structure for the regulation of gene expression, and identify a mechanism by which this nuclear organisation can be developmentally regulated.

Cargo transport: a complex tale of the kinesin tail

The plus-end directed motor protein Kinesin-1 is a major effector of microtubule-mediated transport, moving a wide range of cargo around cells. How cargo specificity is achieved and how motor transport is regulated are still not fully understood, particularly in in vivo developmental contexts. Isabel Palacios and colleagues (p. 176) make use of the multiple functions of Kinesin-1 in the Drosophila oocyte to analyse how different kinesin heavy chain (KHC) domains contribute to different activities. The authors focus particularly on the tail region, which is involved in auto-inhibition and cargo binding. Although most kinesin functions are impaired in the absence of this region, some appear to be relatively unaffected. Notably, their data suggest that the auto-inhibitory IAK domain has a function independent of its auto-inhibitory activity, while the microtubule binding AMB domain is essential for transport of certain cargoes. Overall, this study showcases the distinct requirements of different cargoes for particular KHC domains – highlighting the diversity of kinesin-mediated transport mechanisms.

The plus-end directed motor protein Kinesin-1 is a major effector of microtubule-mediated transport, moving a wide range of cargo around cells. How cargo specificity is achieved and how motor transport is regulated are still not fully understood, particularly in in vivo developmental contexts. Isabel Palacios and colleagues (p. 176) make use of the multiple functions of Kinesin-1 in the Drosophila oocyte to analyse how different kinesin heavy chain (KHC) domains contribute to different activities. The authors focus particularly on the tail region, which is involved in auto-inhibition and cargo binding. Although most kinesin functions are impaired in the absence of this region, some appear to be relatively unaffected. Notably, their data suggest that the auto-inhibitory IAK domain has a function independent of its auto-inhibitory activity, while the microtubule binding AMB domain is essential for transport of certain cargoes. Overall, this study showcases the distinct requirements of different cargoes for particular KHC domains – highlighting the diversity of kinesin-mediated transport mechanisms.

Regulating stem cell fate with CRISPRe

The ability to manipulate genomes has been significantly advanced by the development of the CRSIPR/Cas9 technology, in which the Cas9 endonuclease is targeted to specific sites in the genome by single-guide RNAs (sgRNA) – short sequences complementary to the genomic locus of interest. This approach has been further developed to allow regulation of gene expression at particular loci (a system referred to as CRISPRe): a catalytically inactive version of Cas9 (dCas9) can be fused to transcription activation (e.g. VP64) or repression (e.g. KRAB) domains and targeted to the desired genomic locus by sgRNA. Now, René Maehr and colleagues (p. 219) apply the CRISPRe system in human pluripotent stem cells. Their work provides a proof-of-principle that dCas9 fused to either VP64 or KRAB can regulate mRNA and protein levels of a gene targeted by sgRNA, with consequent effects on cell differentiation. This technique provides a widely applicable method to control gene expression, and hence manipulate cell fate, in stem cells.

The ability to manipulate genomes has been significantly advanced by the development of the CRSIPR/Cas9 technology, in which the Cas9 endonuclease is targeted to specific sites in the genome by single-guide RNAs (sgRNA) – short sequences complementary to the genomic locus of interest. This approach has been further developed to allow regulation of gene expression at particular loci (a system referred to as CRISPRe): a catalytically inactive version of Cas9 (dCas9) can be fused to transcription activation (e.g. VP64) or repression (e.g. KRAB) domains and targeted to the desired genomic locus by sgRNA. Now, René Maehr and colleagues (p. 219) apply the CRISPRe system in human pluripotent stem cells. Their work provides a proof-of-principle that dCas9 fused to either VP64 or KRAB can regulate mRNA and protein levels of a gene targeted by sgRNA, with consequent effects on cell differentiation. This technique provides a widely applicable method to control gene expression, and hence manipulate cell fate, in stem cells.

PLUS:

Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a lipid mediator formed by the metabolism of sphingomyelin. Recent studies have shown that crucial events during embryogenesis, such as angiogenesis, cardiogenesis, limb development and neurogenesis, are regulated by S1P signalling. Here, Timothy Hla and colleagues provide an overview of S1P signalling in development and in disease.

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a lipid mediator formed by the metabolism of sphingomyelin. Recent studies have shown that crucial events during embryogenesis, such as angiogenesis, cardiogenesis, limb development and neurogenesis, are regulated by S1P signalling. Here, Timothy Hla and colleagues provide an overview of S1P signalling in development and in disease.

See the Development at a Glance poster article on p. 5

How unique is the human neocortex?

The human cerebral cortex is generally considered the most complex organ, and is the structure that we hold responsible for the repertoire of behavior that distinguishes us from our closest living and extinct relatives. At a recent Company of Biologists Workshop, ‘Evolution of the Human Neocortex: How Unique Are We?’ held in September 2013, researchers considered new information from the fields of developmental biology, genetics, genomics, molecular biology and ethology to understand unique features of the human cerebral cortex and their developmental and evolutionary origin.

The human cerebral cortex is generally considered the most complex organ, and is the structure that we hold responsible for the repertoire of behavior that distinguishes us from our closest living and extinct relatives. At a recent Company of Biologists Workshop, ‘Evolution of the Human Neocortex: How Unique Are We?’ held in September 2013, researchers considered new information from the fields of developmental biology, genetics, genomics, molecular biology and ethology to understand unique features of the human cerebral cortex and their developmental and evolutionary origin.

See the Meeting Review by Zoltan Molnar and Alex Pollen on p. 11

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

(13 votes)

(13 votes)