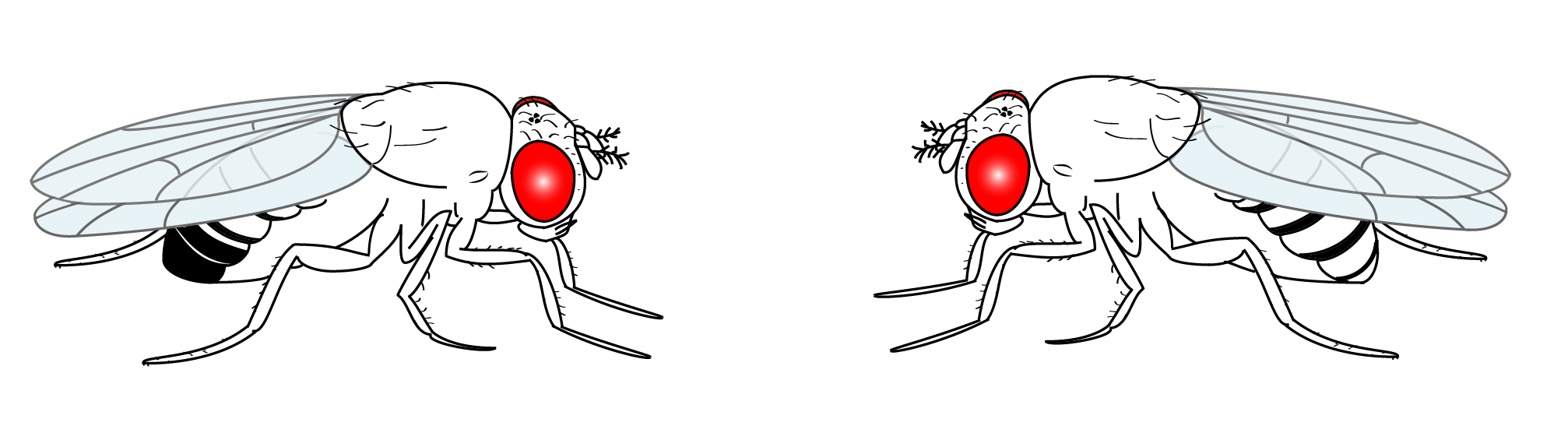

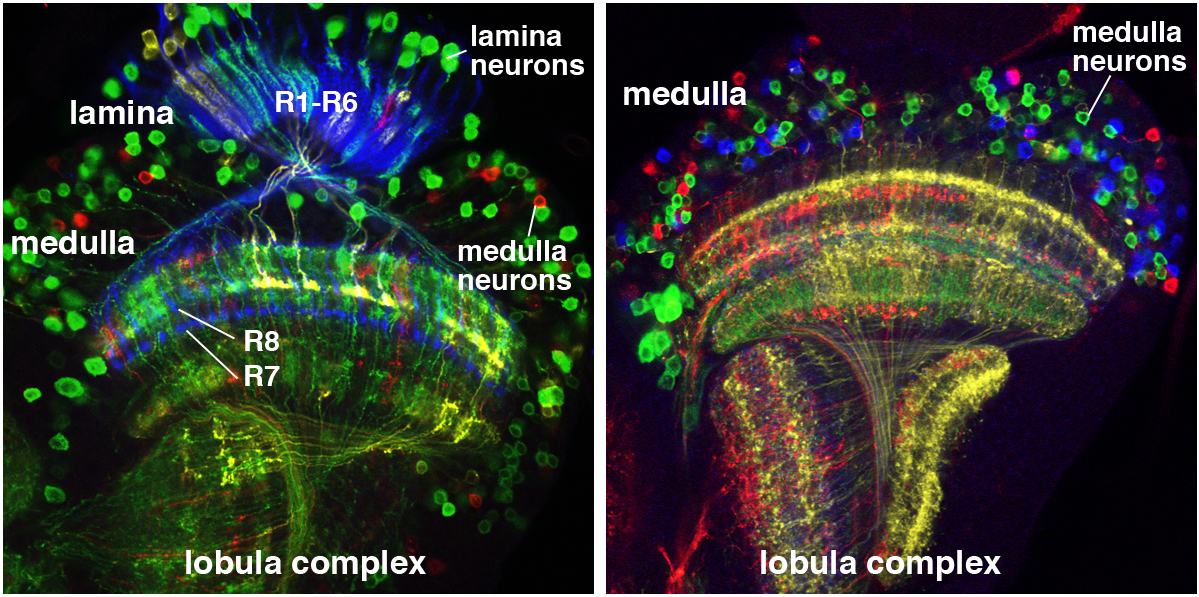

My name is Nana and I’m a third year PhD student at the MRC National Institute for Medical Research in London. Our lab is in the Division of Molecular Neurobiology—so it comes as no surprise that we work on the brain! All animals need a functional brain to interpret sensory information and to produce behavioural responses. In the brain, a large diversity of cell types, neurons and glial cells, form complicated networks. We are interested in how neurons and glia are generated, and how neurons can form specific connections with each other. These connections are formed in a stepwise coordinated manner, and our model to study neural circuit assembly is the visual system of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster.

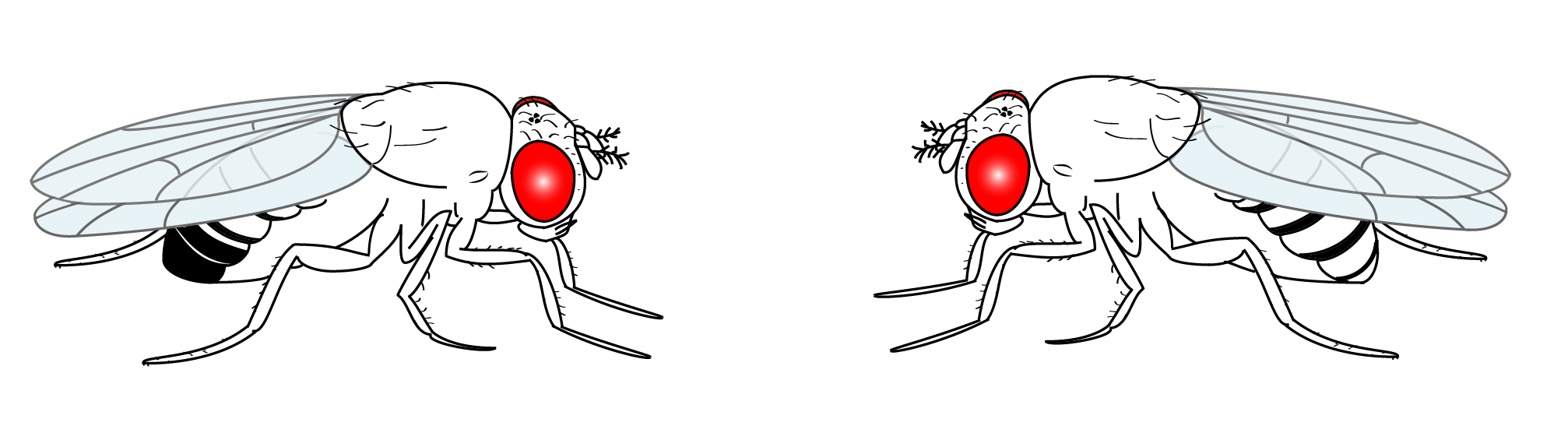

Cartoon of a Drosophila male (left) and female (right). From Shimosako et al. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-655-9_4

Cartoon of a Drosophila male (left) and female (right). From Shimosako et al. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-655-9_4

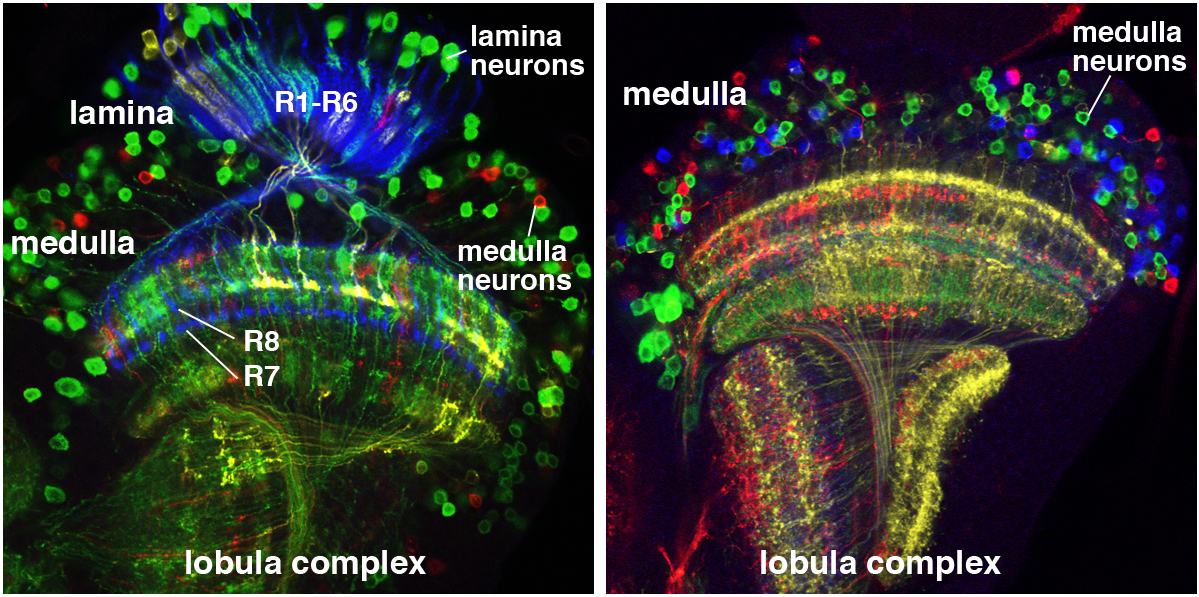

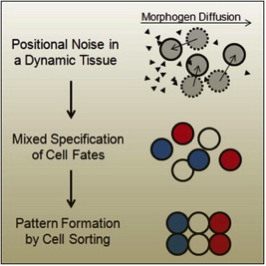

The Drosophila visual system, as its vertebrate counterpart, is organised into synaptic units of columns and layers. These are not only important for visual information processing, but also during development make it easier for each neuron to find its partner. I, in particular, am investigating how neurons target their axons and dendrites into specific layers in the brain.

My model organism, Drosophila melanogaster, is a small fly weighing about 1mg. The life cycle of flies is very short, and the embryo develops into an adult in 10 days at 25 °C. This is great because you know the outcome of experiments relatively quickly, compared to animals with longer life cycles. Flies live in tubes containing fly food at the bottom. Fly food consists of cornmeal, yeast, and other nutrients they need. The flies will lay eggs on the food, the hatched larvae will eat through the food, and eventually crawl up the side of the tube to pupate. After about 4 days, those flies hatch, and the whole cycle continues.

A fly vial. Larvae and adults eat the food at the bottom, where eggs are also laid. Larvae crawl up the wall when they’re ready to pupate, and a few days later, adults hatch.

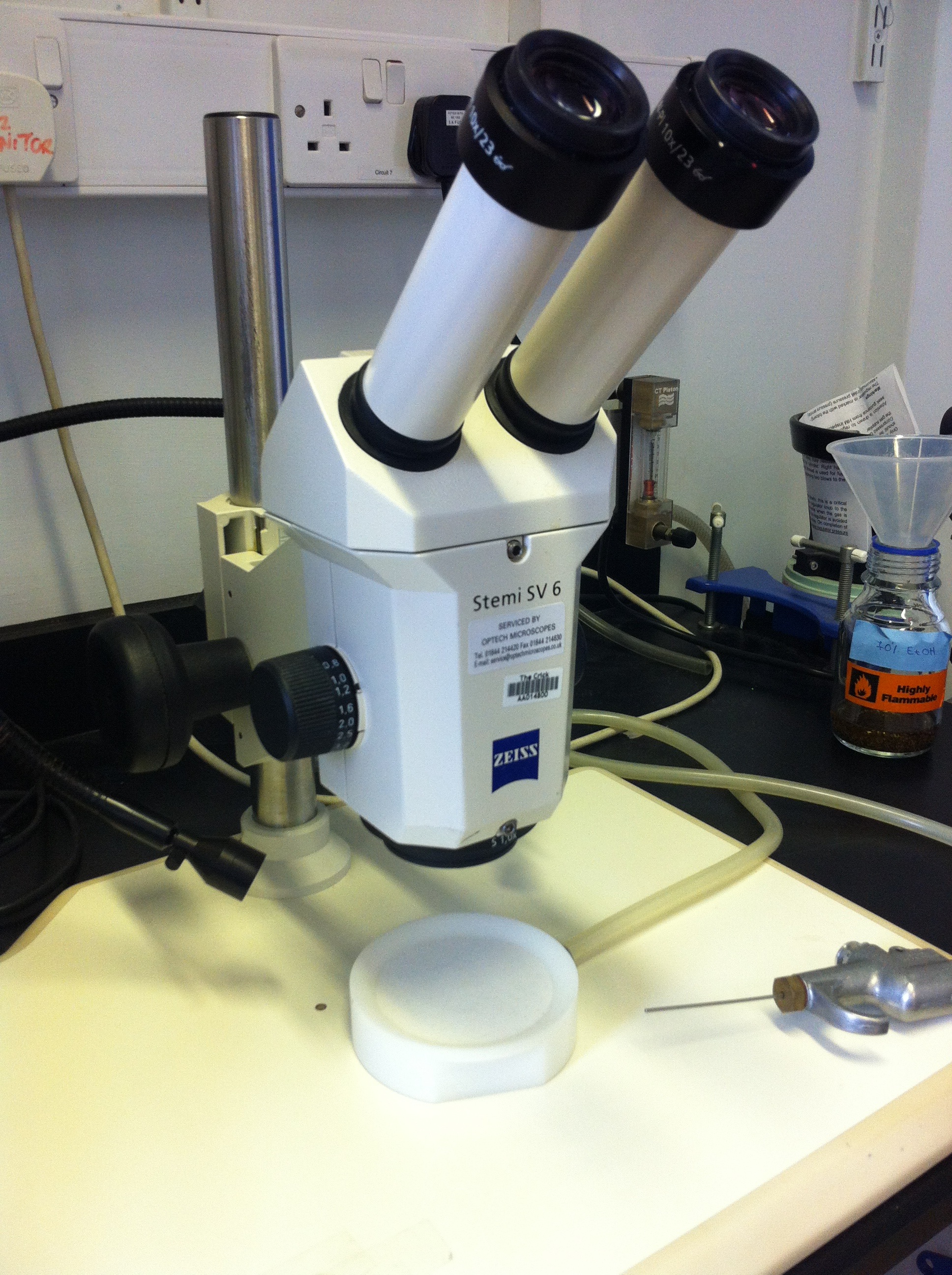

Most “fly people” start their day in the fly room. It’s a temperature controlled room, maintained at 22 °C, with workstations consisting of dissecting microscopes and fly pads. Fly pads release a controlled amount of CO2, so the flies placed on the pads fall asleep. It’s absolutely essential to have this, otherwise we won’t be able to sort through the flies if they’re still moving! We have two other rooms with different temperatures—18 °C and 25 °C. Those don’t have workstations, but are used to keep our fly stocks. The life cycle of flies varies depending on the temperature, and it gets shorter as the temperature increases. The 18 °C room is for stocks which we don’t use on a daily basis, but need to keep for future experiments. 25 °C is the temperature we most frequently use for experiments. Flies are happy at 25 °C, they lay eggs well, and the timing of development is well characterised so we know precisely what happens at certain time points. For example, we know when the embryos hatch, the larvae moult, and when the pigments become visible in the eyes and wings of pupae. Not only can we see these external features, but we also know where the axons of well-studied neurons are at particular developmental stages.

A typical fly workstation, with a microscope, CO2 pad and a CO2 “gun”, which we use to insert CO2 directly into vials so flies fall asleep.

In the fly room, we first collect “virgins”. Virgins are females that have never mated with males, and we need these for genetic crosses. To ensure that the females are virgins, we collect them within a few hours of their hatching before they are developed enough to mate. And since most flies hatch in the morning, we’re most likely to find virgins when we first get to work. Once we have enough virgins, and depending on when we need the offspring for an experiment, we set up the crosses. To set up a cross, we simply retrieve the males and virgins of the right genotype from their vials, and move them to a new vial. The males then proceed to court the females within minutes.

Flies are asleep on the CO2 pad, so we can select the virgins (near the front).

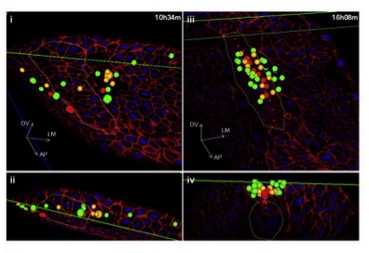

After collecting virgins, I usually move on to dissections. The cells of the visual system are generated from the third instar larval stage onwards, and continue to develop throughout pupal stages. Since my neurons of choice target their axons in late pupal development, most dissections I do are of pupae. I need to stage the pupae, meaning I collect the white prepupae, which have freshly-pupated and still retain the larval white colour, and count the number of hours after puparium formation (APF). The white prepupal stage corresponds to 0 hours APF, and the flies hatch between 90-100 hours. I look at anything between 24 and 85 hours APF depending on the experiment. We dissect fly brains under a microscope, using a tweezer in each hand. The great thing about flies is that the number of samples you can dissect is not limited by any laws or rules. The only factor which limits the sample number is how difficult it is to get progeny of crosses with the right genotype—when the flies have multiple transgenes loaded onto most of their chromosomes, they are not as healthy as wild type and sometimes refuse to hatch!

WPP are collected on a plate with agar containing grape juice. They’re very small, as you can see compared to the pencil.

The best thing about using Drosophila is its extensive genetic toolbox. Using the Gal4-UAS system, we can express any transgene in specific cell types. Additional genetic “tricks” allow us to label neurons or glia of interest in the brain, also at a single cell level. This is very useful when we want to investigate the function of genes, and for example would like to know whether they’re required in a specific cell. Another advantage of flies is that the genome is completely sequenced. We have good knowledge of the sequence of all genes often down to the single base. There are some un-annotated (potential) genes in the genome, and there’s always excitement if you work on them—because if you find a function for them, you get to pick the name of the gene. I think fly gene names are really inventive and fun, which help you remember them. swiss cheese, sex-lethal, technical knockout, and tinman to name a few!

After dissecting, I take care of my fly stocks before lunch. One annoying thing about flies is that we can’t cryopreserve the embryos, so we always need to maintain stocks as live flies. This means we need to “flip stocks” every few weeks, which involves transferring the flies from their old tube to a new tube.

At lunchtime, all the fly groups eat together. There are three fly labs at NIMR, with around 30 people in total. We all share the fly room and equipment, and give experimental advice to each other. I see everyone every day in the fly room and in the canteen, and we certainly build amazing friendships. I’d say that’s a perk of working in a communal fly environment!

The countryside view from the NIMR canteen.

The first thing I do in the afternoon is to incubate my dissected brain samples from the previous day in secondary antibody. They would have been incubated in primary antibody overnight, and after 2.5 hours incubation in secondary antibody at room temperature, they are good to go.

To prepare the brains for confocal microscopy, I mount them on a glass slide. We don’t slice the brains, but look at them as a whole because they are very small. We place the tiny brains in a drop of mounting medium, and then under a fluorescence dissecting microscope, shift their orientation in the medium. This gives us the perfect orientation to visualise the brain in a reproducible manner, but it requires a lot of patience, and your hands need to learn to make adjustments in the μm range. It’s essential to get this right, otherwise we won’t be able to tell whether axon projections are reaching the correct area of the brain. And we need to know if it’s a phenotype, or just looks like one because it’s sloppily mounted!

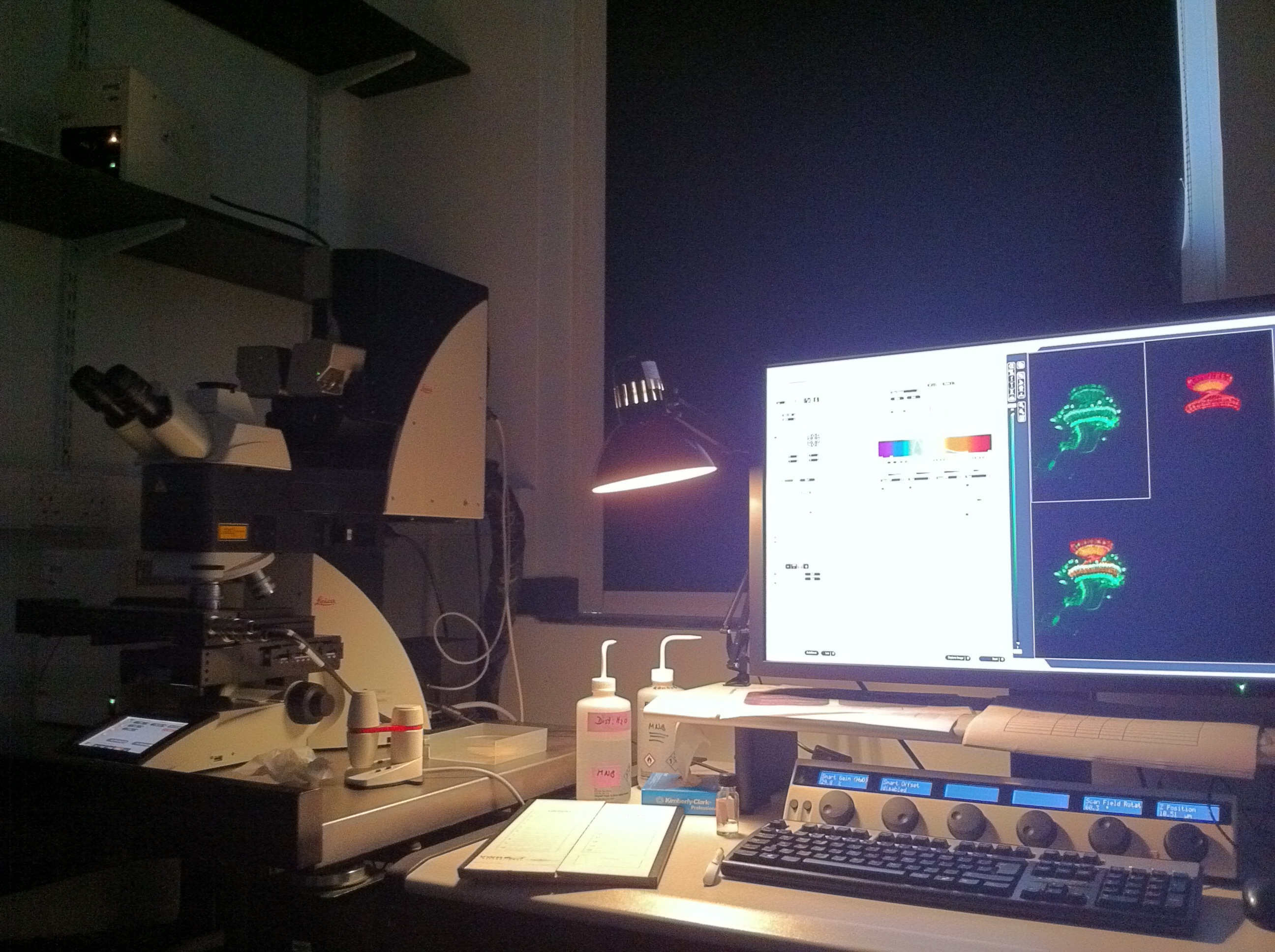

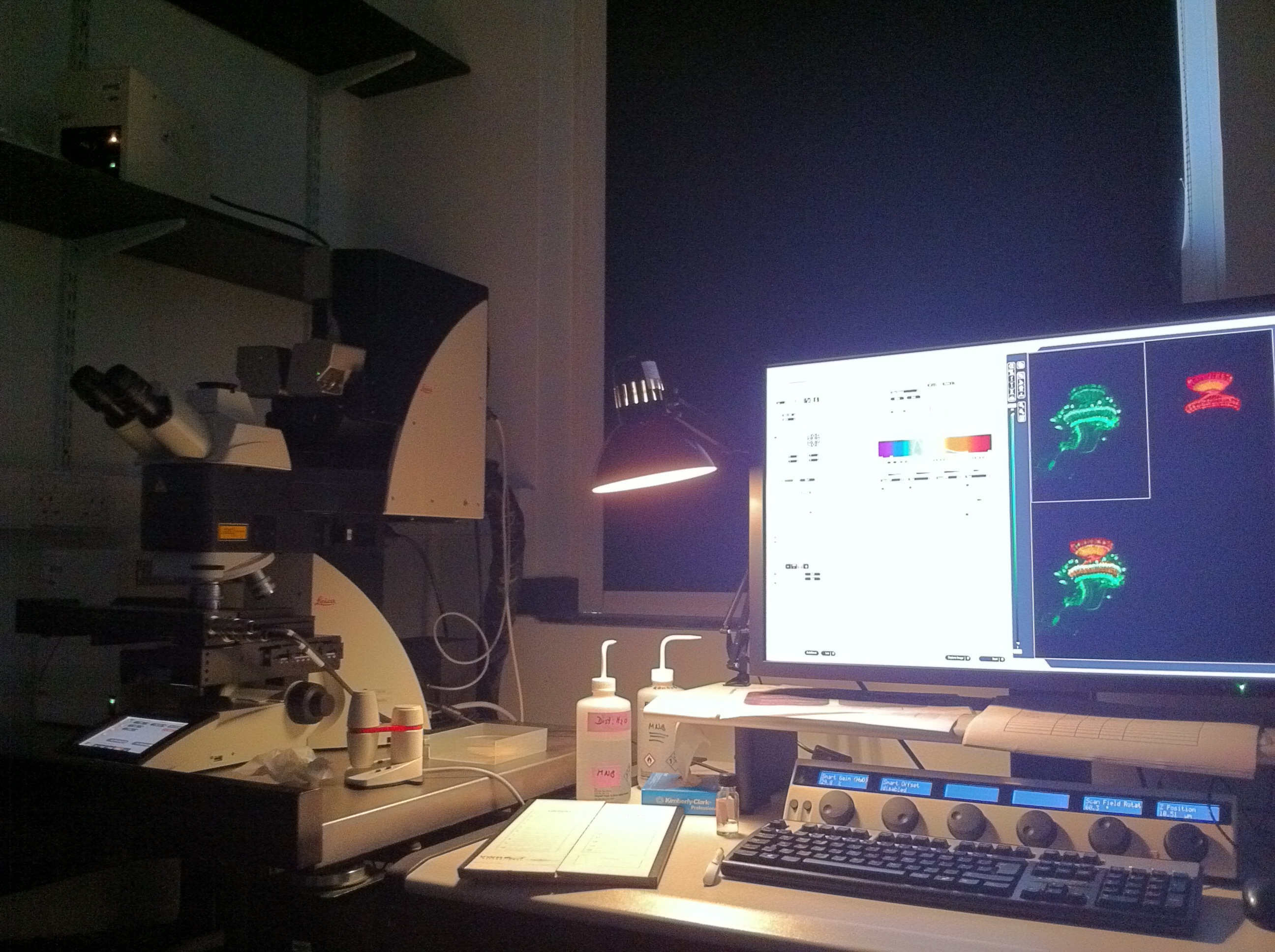

A typical set up of a confocal microscope.

The confocal microscope is arguably the most important thing our lab uses. We need to look at fluorescently labelled neurons at the single cell level so it’s crucial to have a microscope with high enough resolution. We use techniques which allow us to label our cells with sometimes up to 5 different colours in the same sample, so generating an image (with multiple focal planes) could take a long time. The current microscope we have is only a few years old, and is able to do fast scans. Even then, when I have to follow the neuronal processes across the brain, scans could take about an hour. Still, it is very rewarding to look at the final image, which labels neurons (or antibodies recognising proteins) in different colours.

A rainbow in the fly visual system. We use a technique called Flybow to identify individual neurons in the Drosophila optic lobe. Left: Timofeev et al. 2012; Right: from D. Hadjieconomou.

The final thing I do before calling it a day is to go to the fly room and collect virgins again. This time I collect the flies that have hatched during the day. Then I store my flies at 18 °C for the evening, and after a night’s rest, they will be ready for me again in the morning.

It’s been 3 years and 8 months since I started working in my current lab. I started off as a research technician, focussing on molecular biology projects to create new transgenic fly lines. Now, I’m fully immersed in the fly genetics and immunohistochemistry—and looking forward to continue working with these cool little guys to find out more about brain development.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

(16 votes)

(16 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(6 votes)

(6 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) We’re excited to announce that our short film, Stem cells – the future: an introduction to iPS cells, is now available in French, German, Italian, Polish and Spanish as well as English, with a supporting quiz for the classroom. You can

We’re excited to announce that our short film, Stem cells – the future: an introduction to iPS cells, is now available in French, German, Italian, Polish and Spanish as well as English, with a supporting quiz for the classroom. You can

Many congratulations to our partner, Dr

Many congratulations to our partner, Dr

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series  (16 votes)

(16 votes)