In Development this week (Vol. 139, Issue 15)

Posted by Seema Grewal, on 10 July 2012

Here are the research highlights from the current issue from Development:

Cxcr4a sets proliferative response to Hh

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway controls both patterning and proliferation during development, but how do embryonic cells distinguish between these activities? On p. 2711, Pia Aanstad and colleagues provide data that indicates that proliferative responses to Hh signalling are context dependent. The researchers show that activation of Hh signalling promotes endodermal cell proliferation in zebrafish gastrula stage embryos but inhibits proliferation in neighbouring non-endodermal cells. Expression of the chemokine receptor Cxcr4a in gastrula stage endoderm determines the proliferative response to Hh signalling, they report, but does not affect the expression of Hh target genes involved in patterning. Finally, they show that Cxcr4a inhibits the activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (a negative regulator of Hh signalling), and propose that Cxcr4a enhances Hh-dependent proliferation by promoting the activity of Gli. Together, these results indicate that Cxcr4a is required for Hh-dependent cell proliferation but not for Hh-dependent patterning. Thus, parallel activation of Cxcr4a might enable Hh signalling to control both patterning and proliferation during development.

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway controls both patterning and proliferation during development, but how do embryonic cells distinguish between these activities? On p. 2711, Pia Aanstad and colleagues provide data that indicates that proliferative responses to Hh signalling are context dependent. The researchers show that activation of Hh signalling promotes endodermal cell proliferation in zebrafish gastrula stage embryos but inhibits proliferation in neighbouring non-endodermal cells. Expression of the chemokine receptor Cxcr4a in gastrula stage endoderm determines the proliferative response to Hh signalling, they report, but does not affect the expression of Hh target genes involved in patterning. Finally, they show that Cxcr4a inhibits the activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (a negative regulator of Hh signalling), and propose that Cxcr4a enhances Hh-dependent proliferation by promoting the activity of Gli. Together, these results indicate that Cxcr4a is required for Hh-dependent cell proliferation but not for Hh-dependent patterning. Thus, parallel activation of Cxcr4a might enable Hh signalling to control both patterning and proliferation during development.

Hh maintains testis somatic stem cells

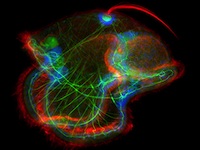

Stem cells are specified and maintained by specific microenvironments called niches. In the Drosophila testis, somatic cyst stem cells (CySCs) give rise to cyst cells, which ensheath the differentiating germline stem cells (GSCs). Both stem cell pools are arranged around a group of somatic cells – the hub – that produce niche signals for both lineages. Now, Christian Bökel and co-workers report that CySC but not GSC maintenance requires Hedgehog (Hh) signalling in addition to Jak/Stat pathway activation (see p. 2663). The researchers report that CySCs unable to transduce the Hh signal are lost through differentiation, whereas Hh pathway overactivation in CySCs increases their proliferation. The additional cells generated by excessive Hh signalling remain confined to the testis tip and retain the ability to differentiate. Because Hh signalling also controls somatic cell populations in the fly ovary and the mammalian testis, these new observations reveal a greater organisational similarity between the somatic components of gonads across the sexes and phyla than previously appreciated.

Stem cells are specified and maintained by specific microenvironments called niches. In the Drosophila testis, somatic cyst stem cells (CySCs) give rise to cyst cells, which ensheath the differentiating germline stem cells (GSCs). Both stem cell pools are arranged around a group of somatic cells – the hub – that produce niche signals for both lineages. Now, Christian Bökel and co-workers report that CySC but not GSC maintenance requires Hedgehog (Hh) signalling in addition to Jak/Stat pathway activation (see p. 2663). The researchers report that CySCs unable to transduce the Hh signal are lost through differentiation, whereas Hh pathway overactivation in CySCs increases their proliferation. The additional cells generated by excessive Hh signalling remain confined to the testis tip and retain the ability to differentiate. Because Hh signalling also controls somatic cell populations in the fly ovary and the mammalian testis, these new observations reveal a greater organisational similarity between the somatic components of gonads across the sexes and phyla than previously appreciated.

ncRNAs keep genes silent

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) help to establish transcriptional gene silencing during development by interacting with DNA and chromatin-modifying enzymes. But do they also help to maintain gene silencing? Here (p. 2792), Chandrasekhar Kanduri and colleagues explore the involvement of the Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA in the maintenance of gene silencing at the Kcnq1 imprinted domain in the mouse embryo. The Kcnq1 domain contains ubiquitously imprinted genes (UIGs), which show imprinted silencing in placental and embryonic tissues; placental-specific imprinted genes (PIGs), which are silenced on the paternal chromosome in the placenta only; and several non-imprinted genes (NIGs). By conditionally deleting the Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA at different stages of mouse development, the researchers show that this ncRNA is required to maintain UIG silencing throughout development, whereas silencing of some PIGs is maintained independently of Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA. Intriguingly, the researchers identify enhancer-specific histone modifications associated with actively transcribed NIGs. These, they propose, may limit the spread of ncRNA-mediated silencing. Together, these results suggest how ncRNAs might maintain transcriptional silencing in a spatiotemporal manner.

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) help to establish transcriptional gene silencing during development by interacting with DNA and chromatin-modifying enzymes. But do they also help to maintain gene silencing? Here (p. 2792), Chandrasekhar Kanduri and colleagues explore the involvement of the Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA in the maintenance of gene silencing at the Kcnq1 imprinted domain in the mouse embryo. The Kcnq1 domain contains ubiquitously imprinted genes (UIGs), which show imprinted silencing in placental and embryonic tissues; placental-specific imprinted genes (PIGs), which are silenced on the paternal chromosome in the placenta only; and several non-imprinted genes (NIGs). By conditionally deleting the Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA at different stages of mouse development, the researchers show that this ncRNA is required to maintain UIG silencing throughout development, whereas silencing of some PIGs is maintained independently of Kcnq1ot1 ncRNA. Intriguingly, the researchers identify enhancer-specific histone modifications associated with actively transcribed NIGs. These, they propose, may limit the spread of ncRNA-mediated silencing. Together, these results suggest how ncRNAs might maintain transcriptional silencing in a spatiotemporal manner.

In vivo activities of miRNAs revealed

Hundreds of microRNAs (miRNAs) – short RNAs that mediate networks of post-transcriptional gene regulation – have been recorded in animals. Because cell-based assays and bioinformatics provide evidence for large numbers of functional targets for individual miRNAs, it is not obvious that manipulation of miRNAs will lead to interpretable phenotypes at the organismal level. However, on p. 2821, Eric Lai and co-workers describe a genome-wide transgenic resource for the conditional expression of Drosophila miRNAs and, surprisingly, report that the majority of the miRNA transgenes in their collection induce relatively specific mutant phenotypes when expressed in the developing wing. Many of these phenotypes resemble those produced by alterations in signalling and patterning genes and, notably, their specificities were not predictable from computational studies, thereby highlighting the usefulness of in vivo phenotypic assays of miRNA activity. Finally, the unexpectedly broad capacity of different miRNAs to generate specific dominant phenotypes in flies suggests that gain-of-function of diverse mammalian miRNAs may also generate an array of specific disease conditions.

Hundreds of microRNAs (miRNAs) – short RNAs that mediate networks of post-transcriptional gene regulation – have been recorded in animals. Because cell-based assays and bioinformatics provide evidence for large numbers of functional targets for individual miRNAs, it is not obvious that manipulation of miRNAs will lead to interpretable phenotypes at the organismal level. However, on p. 2821, Eric Lai and co-workers describe a genome-wide transgenic resource for the conditional expression of Drosophila miRNAs and, surprisingly, report that the majority of the miRNA transgenes in their collection induce relatively specific mutant phenotypes when expressed in the developing wing. Many of these phenotypes resemble those produced by alterations in signalling and patterning genes and, notably, their specificities were not predictable from computational studies, thereby highlighting the usefulness of in vivo phenotypic assays of miRNA activity. Finally, the unexpectedly broad capacity of different miRNAs to generate specific dominant phenotypes in flies suggests that gain-of-function of diverse mammalian miRNAs may also generate an array of specific disease conditions.

A rib-tickling Hox10 motif

During the development of the vertebrate axial skeleton, Hox genes belonging to paralog group 10 play a role in blocking rib formation in the lumbar region of the vertebral column. Here (p. 2703), Moisés Mallo and colleagues investigate the molecular basis of the rib-repressing function of Hox10 proteins. The researchers identify two conserved motifs (M1 and M2) that flank the homeodomain of Hox10 proteins and show that M1, which is located next to the homeodomain’s N-terminal end, is required for Hox10 rib-repressing activity in mice. M1 contains two potential phosphorylation sites, they report, mutation of which to alanines results in a total loss of the rib-repressing properties of Hox10 proteins. Other experiments suggest that the activity of M1 requires interactions with more N-terminal parts of Hox10 and that M1 might also regulate Hox10 activity by altering the protein’s DNA-binding affinity through changes in the phosphorylation state of two conserved tyrosines in the homeodomain. Together, these results provide new insights into the regulation of rib development by Hox10 proteins.

During the development of the vertebrate axial skeleton, Hox genes belonging to paralog group 10 play a role in blocking rib formation in the lumbar region of the vertebral column. Here (p. 2703), Moisés Mallo and colleagues investigate the molecular basis of the rib-repressing function of Hox10 proteins. The researchers identify two conserved motifs (M1 and M2) that flank the homeodomain of Hox10 proteins and show that M1, which is located next to the homeodomain’s N-terminal end, is required for Hox10 rib-repressing activity in mice. M1 contains two potential phosphorylation sites, they report, mutation of which to alanines results in a total loss of the rib-repressing properties of Hox10 proteins. Other experiments suggest that the activity of M1 requires interactions with more N-terminal parts of Hox10 and that M1 might also regulate Hox10 activity by altering the protein’s DNA-binding affinity through changes in the phosphorylation state of two conserved tyrosines in the homeodomain. Together, these results provide new insights into the regulation of rib development by Hox10 proteins.

Modelling EGFR patterning of fly epithelium

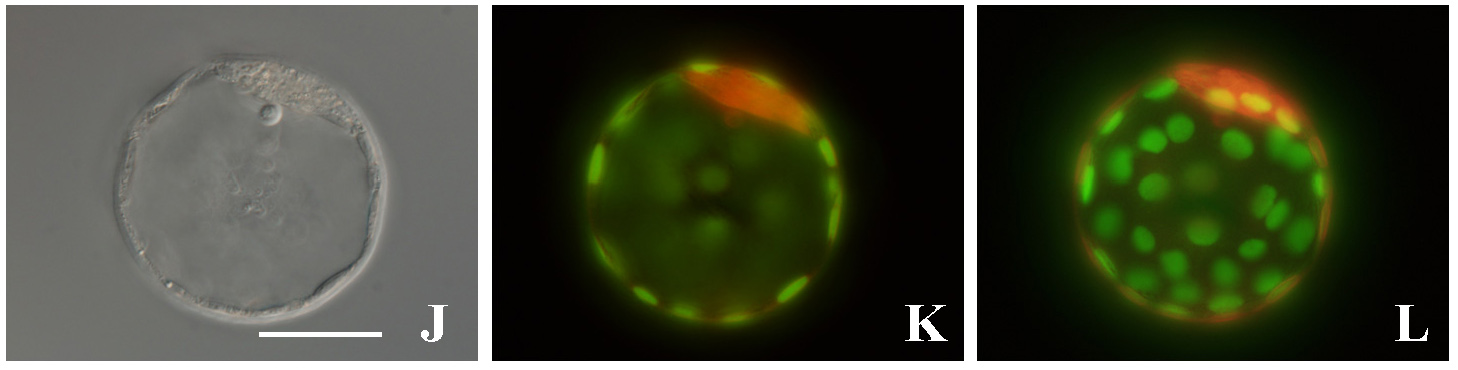

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling regulates numerous processes throughout Drosophila development. For example, during oogenesis, an EGFR activation gradient induced by Gurken (a TGFα-like ligand secreted from the oocyte) patterns the follicular epithelium. On p. 2814, Stanislav Shvartsman and colleagues present a revised mathematical model for this important process, which initiates the formation of two dorsal eggshell appendages. Each of these appendages is derived from a primordium that comprises a patch of cells expressing the transcription factor gene broad (br) and an adjacent strip of cells expressing rhomboid (rho), which encodes a protease in the EGFR pathway. Previous models of eggshell patterning have not fully accounted for the coordinated expression of br and rho. The new model, however, proposes that the sequential action of feed-forward loops and Notch-mediated juxtacrine signals activated by the EGFR signalling gradient establishes rho expression, successfully describes the wild-type br and rho expression patterns, and accounts for changes in these patterns in response to genetic perturbations.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling regulates numerous processes throughout Drosophila development. For example, during oogenesis, an EGFR activation gradient induced by Gurken (a TGFα-like ligand secreted from the oocyte) patterns the follicular epithelium. On p. 2814, Stanislav Shvartsman and colleagues present a revised mathematical model for this important process, which initiates the formation of two dorsal eggshell appendages. Each of these appendages is derived from a primordium that comprises a patch of cells expressing the transcription factor gene broad (br) and an adjacent strip of cells expressing rhomboid (rho), which encodes a protease in the EGFR pathway. Previous models of eggshell patterning have not fully accounted for the coordinated expression of br and rho. The new model, however, proposes that the sequential action of feed-forward loops and Notch-mediated juxtacrine signals activated by the EGFR signalling gradient establishes rho expression, successfully describes the wild-type br and rho expression patterns, and accounts for changes in these patterns in response to genetic perturbations.

Plus…

Toward a blueprint for regeneration

Tissue regeneration has been studied for hundreds of years, yet remains one of the less understood topics in developmental biology. The recent Keystone Symposium on Mechanisms of Whole Organ Regeneration, reviewed by Gregory Nachtrab and Kenneth Poss, brought together biologists, clinicians and bioengineers representing an impressive breadth of model systems and perspectives. See the Meeting Review on p. 2639

Tissue regeneration has been studied for hundreds of years, yet remains one of the less understood topics in developmental biology. The recent Keystone Symposium on Mechanisms of Whole Organ Regeneration, reviewed by Gregory Nachtrab and Kenneth Poss, brought together biologists, clinicians and bioengineers representing an impressive breadth of model systems and perspectives. See the Meeting Review on p. 2639

Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: annelids

Annelids (the segmented worms) have a long history in studies of animal developmental biology, particularly with regards to their cleavage patterns during early development and their neurobiology. As reviewed by David Ferrier, Annelida are playing an important role in deducing the developmental biology of the last common ancestor of the protostomes and deuterostomes.

Annelids (the segmented worms) have a long history in studies of animal developmental biology, particularly with regards to their cleavage patterns during early development and their neurobiology. As reviewed by David Ferrier, Annelida are playing an important role in deducing the developmental biology of the last common ancestor of the protostomes and deuterostomes.

See the Primer on p. 2643

Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum

Spiders belong to the chelicerates, which is an arthropod group that branches basally from myriapods, crustaceans and insects. Hilbrant, Damen and McGregor describe how the growing number of experimental tools and resources available to study Parasteatoda development have provided novel insights into the evolution of developmental regulation and have furthered our understanding of metazoan body plan evolution.

Spiders belong to the chelicerates, which is an arthropod group that branches basally from myriapods, crustaceans and insects. Hilbrant, Damen and McGregor describe how the growing number of experimental tools and resources available to study Parasteatoda development have provided novel insights into the evolution of developmental regulation and have furthered our understanding of metazoan body plan evolution.

See the Primer on p. 2655

Also see the related Editorial by Nipam Patel, Development‘s evo-devo Editor.

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (14 votes)

(14 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)