Essay nominee 2 – There’ll be dragons?

Posted by the Node, on 18 July 2012

Below is the second of two essays nominated in our essay competition “Developments in development”. The other nominated essay appeared on the Node yesterday. Please read both essays, and come back on or after July 19 to cast your vote for the winner. The winning essay will appear in Development later this year. See the announcement for author bios, and read the first essay here.

There‘ll be dragons? – The coming era of artificially altered development

By Máté Varga

As part of their yearly April’s Fool prank series, in 2006 The Economist ran a short article in their “Science and technology” section about a fictional company that planned to create mythical creatures in flesh and blood on demand. Scientists working for GeneDupe (as the company was called), would use their extensive knowledge about development, to introduce the genome of a lizard or horse into a computer, and with the help of evolutionary algorithms “mutate” it in a way that the new genome would be capable of giving rise to a dragon or unicorn, respectively. The DNA would be synthesized, introduced into an enucleated egg, and presto, in only a few months time the happy customer would walk away with a mythical pet.

Although the story contained several giveaways about the spoof, and anyone vaguely familiar with the status of the field could immediately see that the whole thing is nonsense, the article still had some aura of plausibility, as any good hoax should. More naive readers could have imagined it happening, and even science-types could have wondered, what if…?

Six years on, we are still far, far away from possessing the knowledge that would be required to recreate GeneDupe’s feat in the real world. But, arguably, we are inching closer. As more and more model and non-model organisms have their genomes unraveled, as we learn how genes are organized in developmental networks, as we decipher their enhancers and epigenetic codes, and find the exact mutations that can cause evolutionary changes, we do progress towards a future when GeneDupe-style simulations will become not only possible, but also common and, in certain situations, desirable.

This should not come as a surprise to anyone. After all, we have been tinkering with embryos for hundreds of years and even directly with genes for decades in order to get a comprehensive understanding of how a single fertilized egg can become a complex three-dimensional creature. A creature with intricate inner organ systems that can maintain it throughout its life and help it to react to its environment, adapt and procreate to have its genes passed on. Putting it more bluntly: just like Sylar, the negative protagonist of the TV series “Heroes”, we, developmental biologists, dissect things to see “what makes them tick”.

But once we have that knowledge, an obvious next step would be to try to use it, to control and alter developmental mechanisms in predictable ways – first in silico, then in vivo. This does not seem like a huge step from today’s transgenic and genome editing technologies, yet it would mean genome modification on a different level. Today’s transgenic approaches are, to a certain extent, still based on trial and error, as a comprehensive understanding of how gene regulation works is still missing. Acquiring that knowledge will enable us to introduce changes in the transcriptional program with surgical precision. And then, from mere tinkering-apprentices we would graduate to become Master Craftsmen, on par or not so far behind the Tinkerer-in-Chief, Natural Selection.

We have to be prepared that when we get the ability to do this sort of genetic engineering, the media coverage and reaction will be overwhelming. As Philip Ball describes in his wonderful book “Unnatural”, most human cultures possess a primordial fear of everything they consider to be against Nature’s will, and more often than not hold firmly to the irrational conviction that anything that does not exist in nature is against this will. This psychological reaction was on full display three decades ago, during the IVF debate, and can be seen these days in the gut-driven opposition against genetically modified plants (GMOs).

Therefore, it doesn’t take an oracle to foresee the debate that will ensue once a targeted approach of altering development will be available. The ghosts of Dr. Moreau and Frankenstein will be promptly summoned, scientists will be accused (yet again) of playing God. Outlandish claims will be made, biological equivalents of nanotech’s infamous “grey goo” meme will appear. Ordinary people might think that the end of the world is nigh, crazy biologists are just moments away of unleashing legions of deadly creatures on the unsuspecting inhabitants of the planet.

But amongst the brouhaha, valid arguments and well-grounded fears about the possible misuse of the technology will also be voiced. We should not only listen to these, but also anticipate them. As the recent public debate about the research on artificially modified influenza strains shows, even the scientific community can be caught off-guard with technological progress.

A blanket ban on the use of the novel technology would be useless and unworkable. Once the knowledge exists, people will try to use it. However, to state the obvious, what is doable, is not necessarily desirable, so we ought to seek a consensus on what should be ethically acceptable and what not. The rules should be straightforward and easily understandable even by a lay audience, as this is the only way not to repeat the PR-debacle of plant geneticists in the GMO-debate. For example, genetic modification of rare species threatened by uncurable diseases in order to avoid extinction could be favoured. Similarly, in order to protect whole ecosystems from collapse, altering key ecological species that can not adapt fast enough to the accelerating climate change could be considered.

In contrast, GeneDupe-style designer modification of pets or any species in a way that would make them commercially attractive, but would cause unnecessary harm and suffering for the animals, should be forbidden.

Ethically much murkier areas will be the ones that are directly related to developmental biology itself. Evolution does not plan in advance and, therefore, the phenotypes that we can observe today are often the result of historical contingencies (think of the inverted eye of vertebrates). A question that will be surely on several people’s mind is what if one removes these contingencies or introduces different ones. Will Stephen Jay Gould’s much quoted prediction about “rewinding the tape of life” be sustained, as it is widely agreed, and will different outcomes spring to life? Deciding whether this kind of research should be banned altogether, or allowed on a case by case basis, might have long lasting consequences.

And then there is the ethically most loaded question of them all, should the use of such technology on humans be even considered? Given the sorry history of eugenics in the past century, the answer seems like a forgone conclusion. Every single attempt to create the “perfect human” had calamitous consequences and it is hard to see currently any cold-headed rationale that could make a strong case for such programs. But we have to be aware that just as attempts to introduce gene therapy to cure particular diseases were shadowed by rumours of “gene doping”, the emergence of targeted development-altering methods might create the demand in some shadowy corners of the world to use it on humans.

All this, should make us wary. If the emergence of such new technology will catch us, biologists unprepared, in spite of achieving breathtaking things, like modern day Daedaluses we will pay a heavy price for our ineptitude to use our knowledge wisely.

——-

To vote for Máté’s essay, go to the poll

(20 votes)

(20 votes) (15 votes)

(15 votes) We’re pleased to announce the nominees of the first

We’re pleased to announce the nominees of the first  (No Ratings Yet)

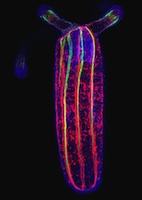

(No Ratings Yet) Currently, most developmental biologists work on one or more of a relatively small number of experimental systems, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Xenopus laevis (frog), Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode), Danio rerio (zebrafish) and Mus musculus (mouse), and their research is largely focused on understanding developmental mechanisms at the genetic, biochemical and molecular levels. This bias toward certain species is easily understood – analyses in these organisms is greatly facilitated by the availability of an array of genetic, molecular and genomic resources that have been generated over the years by large communities of scientists. However, the field of developmental biology has a long and colourful history of experimentation with a remarkably varied assemblage of creatures, and many crucial discoveries were first made in species that are now relatively understudied. Furthermore, some species possess certain remarkable attributes that have generated interest for a very long time. For example, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum, a Mexican salamander) is considered to be the champion of regeneration among vertebrates, and although the number of people working with axolotls is relatively small, they remain a species of great interest because of the potential breakthroughs that might come from them.

Currently, most developmental biologists work on one or more of a relatively small number of experimental systems, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly), Xenopus laevis (frog), Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode), Danio rerio (zebrafish) and Mus musculus (mouse), and their research is largely focused on understanding developmental mechanisms at the genetic, biochemical and molecular levels. This bias toward certain species is easily understood – analyses in these organisms is greatly facilitated by the availability of an array of genetic, molecular and genomic resources that have been generated over the years by large communities of scientists. However, the field of developmental biology has a long and colourful history of experimentation with a remarkably varied assemblage of creatures, and many crucial discoveries were first made in species that are now relatively understudied. Furthermore, some species possess certain remarkable attributes that have generated interest for a very long time. For example, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum, a Mexican salamander) is considered to be the champion of regeneration among vertebrates, and although the number of people working with axolotls is relatively small, they remain a species of great interest because of the potential breakthroughs that might come from them.

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway controls both patterning and proliferation during development, but how do embryonic cells distinguish between these activities? On p.

The Hedgehog (Hh) pathway controls both patterning and proliferation during development, but how do embryonic cells distinguish between these activities? On p.  Stem cells are specified and maintained by specific microenvironments called niches. In the Drosophila testis, somatic cyst stem cells (CySCs) give rise to cyst cells, which ensheath the differentiating germline stem cells (GSCs). Both stem cell pools are arranged around a group of somatic cells – the hub – that produce niche signals for both lineages. Now, Christian Bökel and co-workers report that CySC but not GSC maintenance requires Hedgehog (Hh) signalling in addition to Jak/Stat pathway activation (see p.

Stem cells are specified and maintained by specific microenvironments called niches. In the Drosophila testis, somatic cyst stem cells (CySCs) give rise to cyst cells, which ensheath the differentiating germline stem cells (GSCs). Both stem cell pools are arranged around a group of somatic cells – the hub – that produce niche signals for both lineages. Now, Christian Bökel and co-workers report that CySC but not GSC maintenance requires Hedgehog (Hh) signalling in addition to Jak/Stat pathway activation (see p.  Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) help to establish transcriptional gene silencing during development by interacting with DNA and chromatin-modifying enzymes. But do they also help to maintain gene silencing? Here (p.

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) help to establish transcriptional gene silencing during development by interacting with DNA and chromatin-modifying enzymes. But do they also help to maintain gene silencing? Here (p.  Hundreds of microRNAs (miRNAs) – short RNAs that mediate networks of post-transcriptional gene regulation – have been recorded in animals. Because cell-based assays and bioinformatics provide evidence for large numbers of functional targets for individual miRNAs, it is not obvious that manipulation of miRNAs will lead to interpretable phenotypes at the organismal level. However, on p.

Hundreds of microRNAs (miRNAs) – short RNAs that mediate networks of post-transcriptional gene regulation – have been recorded in animals. Because cell-based assays and bioinformatics provide evidence for large numbers of functional targets for individual miRNAs, it is not obvious that manipulation of miRNAs will lead to interpretable phenotypes at the organismal level. However, on p.  During the development of the vertebrate axial skeleton, Hox genes belonging to paralog group 10 play a role in blocking rib formation in the lumbar region of the vertebral column. Here (p.

During the development of the vertebrate axial skeleton, Hox genes belonging to paralog group 10 play a role in blocking rib formation in the lumbar region of the vertebral column. Here (p.  Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling regulates numerous processes throughout Drosophila development. For example, during oogenesis, an EGFR activation gradient induced by Gurken (a TGFα-like ligand secreted from the oocyte) patterns the follicular epithelium. On p.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling regulates numerous processes throughout Drosophila development. For example, during oogenesis, an EGFR activation gradient induced by Gurken (a TGFα-like ligand secreted from the oocyte) patterns the follicular epithelium. On p.  Tissue regeneration has been studied for hundreds of years, yet remains one of the less understood topics in developmental biology. The recent Keystone Symposium on Mechanisms of Whole Organ Regeneration, reviewed by Gregory Nachtrab and Kenneth Poss, brought together biologists, clinicians and bioengineers representing an impressive breadth of model systems and perspectives. See the Meeting Review on p.

Tissue regeneration has been studied for hundreds of years, yet remains one of the less understood topics in developmental biology. The recent Keystone Symposium on Mechanisms of Whole Organ Regeneration, reviewed by Gregory Nachtrab and Kenneth Poss, brought together biologists, clinicians and bioengineers representing an impressive breadth of model systems and perspectives. See the Meeting Review on p.  Annelids (the segmented worms) have a long history in studies of animal developmental biology, particularly with regards to their cleavage patterns during early development and their neurobiology. As reviewed by David Ferrier, Annelida are playing an important role in deducing the developmental biology of the last common ancestor of the protostomes and deuterostomes.

Annelids (the segmented worms) have a long history in studies of animal developmental biology, particularly with regards to their cleavage patterns during early development and their neurobiology. As reviewed by David Ferrier, Annelida are playing an important role in deducing the developmental biology of the last common ancestor of the protostomes and deuterostomes. Spiders belong to the chelicerates, which is an arthropod group that branches basally from myriapods, crustaceans and insects. Hilbrant, Damen and McGregor describe how the growing number of experimental tools and resources available to study Parasteatoda development have provided novel insights into the evolution of developmental regulation and have furthered our understanding of metazoan body plan evolution.

Spiders belong to the chelicerates, which is an arthropod group that branches basally from myriapods, crustaceans and insects. Hilbrant, Damen and McGregor describe how the growing number of experimental tools and resources available to study Parasteatoda development have provided novel insights into the evolution of developmental regulation and have furthered our understanding of metazoan body plan evolution.