Cellular Reincarnation

Posted by Ewart Kuijk, on 1 October 2013

Stuck! Here I was trapped in this valley with no way out. And it was crowded here, with all of my fibers I sensed numerous peers condemned to a similar fate. The wonderful scenes that could be reached from the top of Mt. Waddington had been illusionary. Was this my reward: being trapped in Fibrocity, the slum of existence? Ignorant of the adventure yet to come, I cursed my fate.

It all got started when “Zygote Enterprises” organized this foolish competition, a race that can be best compared with an obstacle course in the swamp. The countless contestants, including me, were lured by the “Carte Blanche” awaiting the winner. Before the start, we were boasting like little Titans, judging each other’s fitness and calculating our odds. Suddenly, we were launched and hyperactively we raced towards our goal. I realized that my chances to win were next to zero. Then we arrived at a junction and in a lucky burst of inspiration, I directed my nearest competitors to go left, after which most of them unsuspectingly raced off in the wrong direction and I reached the target before the others could. Immediately after I crawled through the opening located in the curved transparent wall it closed, shutting my rivals outside. Unable to avert my eyes, I could see through the wall how the losers perished out there in the damp and hot wilderness, some of them fruitlessly banging the wall with their extremities. Despite the horrific sight, victory tasted good.

Exhausted, but filled with anticipation, I was taken to the top of Mt. Waddington where my triumph would be celebrated and the prize awarded. An employee of “Zygote Enterprises” who introduced herself as OCT4 told me that I would get the blank check in due time, but that she would first show me the view from the top. “It’s marvelous”, she said, “You’ll love it”. She guided me to the edge of Mt. Waddington’s summit, and indeed the view was awesome. “It feels as if I am on top of the world looking down on creation” I told her in a mellow voice.

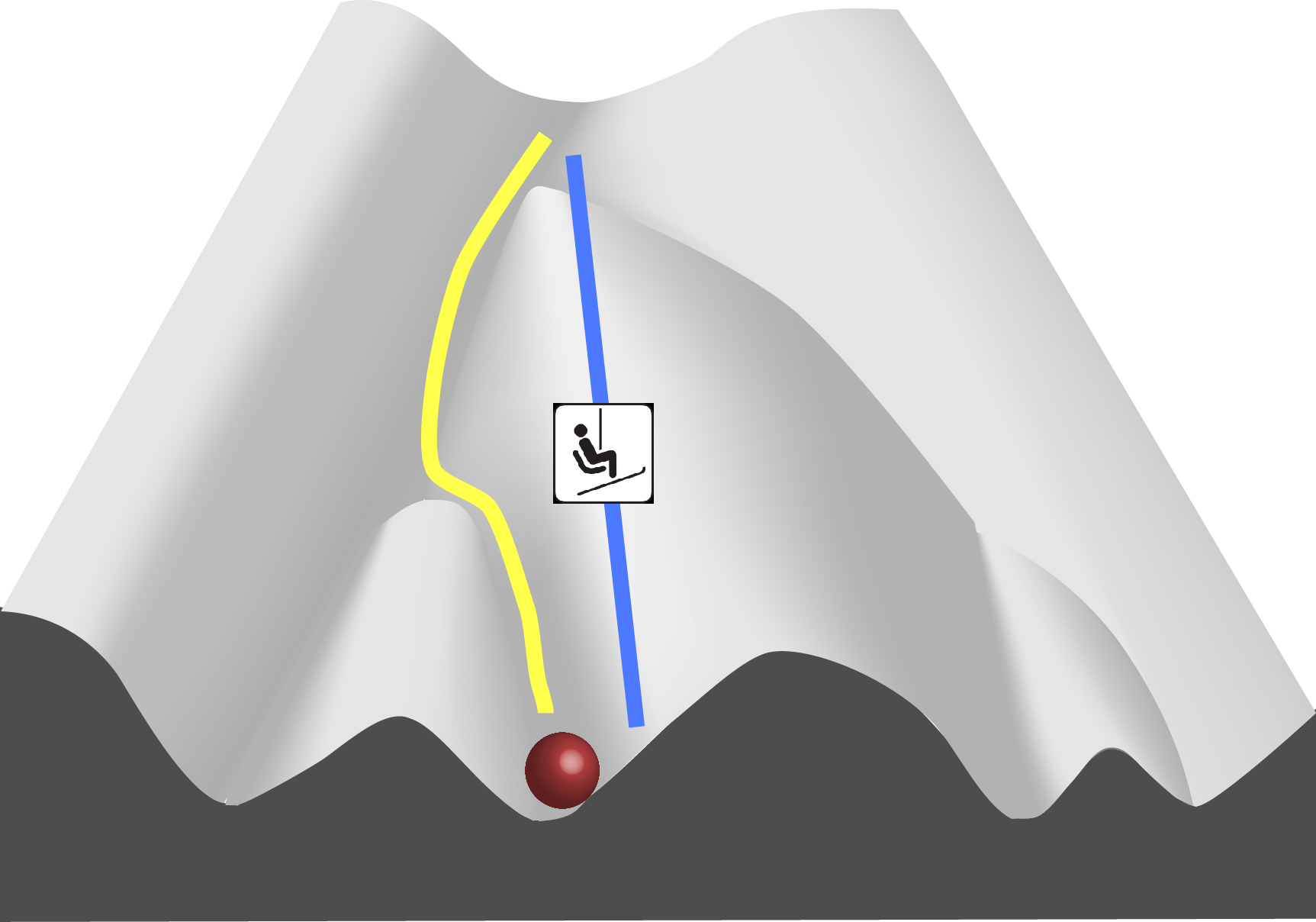

“From here you have a panoramic view into “Les Trois Vallées’” OCT4 told me. “The three large valleys you can see from here are named “Outer Valley”, “Middle Valley”, and “Most Proximal Valley”. OCT4 continued. “If you look carefully, you can see all wonderful places that you can reach from each of these valleys. At the edge of Outer valley you can see Neuronburg and Schwann Lake. Deep down there at the bottom of Middle Valley are Kidney Harbor and Leydig. And there, at the far end of Most Proximal Valley lies Hepatocity with Salivaryg Land’s river glistening beyond”. Dizzied by the dazzling view of unlimited possibilities I grabbed hold of OCT4, afraid I would fall down into the deep. I had hardly steadied myself when OCT4 pushed me hard over the edge. As a marble I started rolling downhill, oblivious of my fate. Had I known where I wanted to go I might have been able to steer myself in the right direction. Faltering, I passed the bifurcation and while contemplating my passivity I entirely missed the second, resulting in the wrong choices at the third and the fourth. In the meantime I had gained so much momentum that all further decisions were pure random. My roller coaster ride came to a sudden halt when I bumped into this non-descript individual. “Welcome to Fibrocity, for those who like to connect”, he said unconvincingly.

It took me a long time to accept my fate in Fibrocity. Finally, I adopted a zen-like state that may be best described as total apathy to cope with my situation, unresponsive to my immediate surroundings. I have no idea for how long I had been in this impassive condition, but I know that it was long enough that I initially failed to notice things were slowly changing around me. Gradually it dawned on me that some of my neighbors had disappeared and I was able to move more freely, a feeling I had not had in ages. Slowly I recovered from the passive state I had been. One by one, all the connections I had with my neighbors were lost. A character that was vaguely familiar to me approached me from a distance. “Hello”, she said “we have met before, remember”. “OCT4” I muttered, while I indeed remembered how she pushed me from the mountain. “Please” she continued, “don’t be angry with me, my intentions are good. Follow me and I will have a surprise for you”. Reluctantly I followed her, cautious for any foul new tricks she would play on me. When I saw where we were heading I was astonished. To my disbelief we drew near a seemingly endless gondola lift going up on the slopes of Mt. Waddington. The lift was brand new, built in Kyoto Japan and signs on the posts read “Takahashi Yamanaka Unlimited”. OCT4 guided me to the small station where the rail cars that come down are sent up again. Just as we entered, a rail car opened its doors. OCT4 stepped inside and intrigued I followed her. She took a seat and pulled me next to her. Immediately the doors closed and the rail car jumped into motion. It was a long journey during which I felt increasingly better at ease. Finally we reached the top of Mt Waddington and the doors swung open. “Go on”, OCT4 said, “It is time for you to collect your prize”. Speechless, I carefully stepped outside. At the exit station a sign read “Welcome to Tir nan-Og, The Land of the Ever Young”. Reborn, I walked to the edge of the mountain top unafraid that OCT4 would push me over again, grateful for the lesson she taught me. In the future, I would carefully choose my next destination, but for the time being I enjoyed the scenery.

(18 votes)

(18 votes)

I think you do challenge people, partially because you present many different views, not just your own.

I think you do challenge people, partially because you present many different views, not just your own.

Correct trophoblast development is essential for placenta function and embryogenesis. In humans, the early stages of this process can only be modelled in vitro using embryonic stem cells (ESCs); however, owing to the failure to identify the stepwise progression that occurs during differentiation, the identity of the resulting cells is not clear. Now, on

Correct trophoblast development is essential for placenta function and embryogenesis. In humans, the early stages of this process can only be modelled in vitro using embryonic stem cells (ESCs); however, owing to the failure to identify the stepwise progression that occurs during differentiation, the identity of the resulting cells is not clear. Now, on  Unlike animals, plants do not set aside germ cells during embryogenesis. Instead, the precursors of these cells, called spore mother cells (SMCs), are generated via a somatic-to-reproductive transition that occurs later in life. Although epigenetic remodelling has been largely studied in the post-meiotic phase of germline development, it is unknown whether pre-meiotic events contribute to cellular reprogramming in the reproductive lineage. Now, on

Unlike animals, plants do not set aside germ cells during embryogenesis. Instead, the precursors of these cells, called spore mother cells (SMCs), are generated via a somatic-to-reproductive transition that occurs later in life. Although epigenetic remodelling has been largely studied in the post-meiotic phase of germline development, it is unknown whether pre-meiotic events contribute to cellular reprogramming in the reproductive lineage. Now, on  Mechanical forces such as blood flow play a key role in regulating vascular remodelling and angiogenesis. Vessel diameter must be tightly controlled to establish correct hierarchical vascular architecture, but how this is achieved is unclear. Now, on

Mechanical forces such as blood flow play a key role in regulating vascular remodelling and angiogenesis. Vessel diameter must be tightly controlled to establish correct hierarchical vascular architecture, but how this is achieved is unclear. Now, on  On

On  The role of mechanical stress in regulating cell shape and tissue morphogenesis is further examined by Shuji Ishihara and Kaoru Sugimura (

The role of mechanical stress in regulating cell shape and tissue morphogenesis is further examined by Shuji Ishihara and Kaoru Sugimura ( The emergence of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the aorta-gonad-mesenephros (AGM) region requires the coordinated activity of multiple transcriptional networks. The transcription factor stem cell leukemia (SCL) is necessary for this process; however, multiple scl isoforms exist and the exact stage at which each is required is unknown. In this issue (

The emergence of haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) from the aorta-gonad-mesenephros (AGM) region requires the coordinated activity of multiple transcriptional networks. The transcription factor stem cell leukemia (SCL) is necessary for this process; however, multiple scl isoforms exist and the exact stage at which each is required is unknown. In this issue ( The formation and maintenance of adipose tissue is essential to many biological processes and when perturbed leads to significant diseases. Here, Jon Graff and colleagues highlight recent efforts to unveil adipose developmental cues, adipose stem cell biology and the regulators of adipose tissue homeostasis and dynamism. See the

The formation and maintenance of adipose tissue is essential to many biological processes and when perturbed leads to significant diseases. Here, Jon Graff and colleagues highlight recent efforts to unveil adipose developmental cues, adipose stem cell biology and the regulators of adipose tissue homeostasis and dynamism. See the  Hox genes encode a family of transcriptional regulators that elicit distinct developmental programmes along the head-to-tail axis of animals. Here, Mallo and Alonso examine the spectrum of molecular mechanisms that control Hox gene expression in model vertebrates and invertebrates. See the

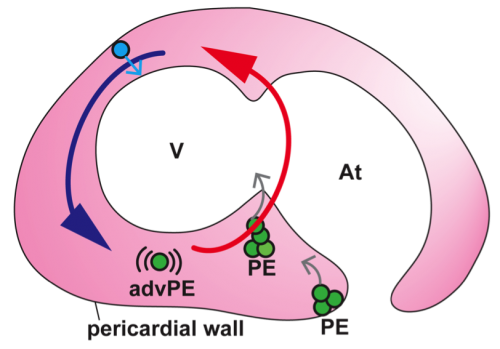

Hox genes encode a family of transcriptional regulators that elicit distinct developmental programmes along the head-to-tail axis of animals. Here, Mallo and Alonso examine the spectrum of molecular mechanisms that control Hox gene expression in model vertebrates and invertebrates. See the  The recent EMBO/EMBL-sponsored symposium ‘Cardiac Biology: From Development to Regeneration’ gathered cardiovascular scientists from across the globe to discuss the latest advances in our understanding of the development and growth of the heart, and application of these advances to improving the limited innate regenerative capacity of the mammalian heart. Christoffels and Pu summarize some of the exciting results and themes that emerged from the meeting. See the

The recent EMBO/EMBL-sponsored symposium ‘Cardiac Biology: From Development to Regeneration’ gathered cardiovascular scientists from across the globe to discuss the latest advances in our understanding of the development and growth of the heart, and application of these advances to improving the limited innate regenerative capacity of the mammalian heart. Christoffels and Pu summarize some of the exciting results and themes that emerged from the meeting. See the  (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)