Four Year International PhD Programme in Stem Cell Biology at the University of Cambridge

Posted by stemcellsjobs, on 5 January 2012

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Studentships starting October 2012

Application deadline 13 January 2012

Interviews to be held 30-31 January 2012

![]()

Stem Cell Biology

Stem Cell Biology

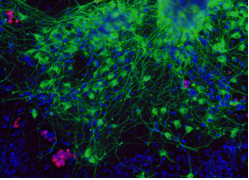

Stem cells are defined by the dual capacity to self-renew and to differentiate. These properties sustain homeostatic cell turnover in adult tissues and enable repair and regeneration throughout the lifetime of the organism. In contrast, pluripotent stem cells are generated in the laboratory from early embryos or by molecular reprogramming. They have the capacity to make any somatic cell type, including tissue stem cells.

Stem cell biology aims to identify and characterise which cells are true stem cells, and to elucidate the physiological, cellular and molecular mechanisms that govern self-renewal, fate specification and differentiation. This research should provide new foundations for biomedical discovery, biotechnological and biopharmaceutical exploitation, and clinical applications in regenerative medicine.

Cambridge Stem Cell Community

The University of Cambridge is exceptional in the depth and diversity of its research in Stem Cell Biology, and has a dynamic and interactive research community that is ranked amongst the foremost in the world. By bringing together members of both the Schools of Biology and Medicine, this four year PhD programme will enable you to take advantage of the strength and breadth of stem cell research available in Cambridge. Choose from over 30 participating host laboratories using a range of experimental approaches and organisms.

Programme Outline

Programme Outline

During the first year students will:

• perform laboratory rotations in three different participating groups working on both basic and translational stem cell biology;

• study fundamental aspects of Stem Cell Biology through a series of teaching modules led by leaders in the field;

• learn a variety of techniques, such as advanced imaging, flow cytometry, and management of complex data sets.

Students are expected to choose a laboratory for their thesis research by June 2013, and will then write a research proposal which will be assessed for the MRes Degree in Stem Cell Biology. Students will then normally commence a three year PhD.

Visit http://www.stemcells.cam.ac.uk/careers-study/studentships/ for full details.

(1 votes)

(1 votes) Why should a developmental biologist be interested in a book about the nucleus? Almost 80 years ago, Conrad Waddington put forward ideas about how gene products could regulate development. In modern parlance, much of development is the result of the differential use of the same genome in different cell types and at different developmental stages within the same organism. This originates in the nucleus, where the processes that act upon the genome – transcription, replication, repair – occur. In developmental biology papers it is not uncommon to find a final summary figure in which a signaling pathway ends up pointing into an oval-shaped nucleus, devoid of any structure or organization, save for a linear depiction of a target gene locus. However, the nucleus is not a homogenous space and neither is the genome in its natural nuclear environment arranged in a linear fashion.

Why should a developmental biologist be interested in a book about the nucleus? Almost 80 years ago, Conrad Waddington put forward ideas about how gene products could regulate development. In modern parlance, much of development is the result of the differential use of the same genome in different cell types and at different developmental stages within the same organism. This originates in the nucleus, where the processes that act upon the genome – transcription, replication, repair – occur. In developmental biology papers it is not uncommon to find a final summary figure in which a signaling pathway ends up pointing into an oval-shaped nucleus, devoid of any structure or organization, save for a linear depiction of a target gene locus. However, the nucleus is not a homogenous space and neither is the genome in its natural nuclear environment arranged in a linear fashion. Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research.

Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research. Benchfly

Benchfly

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Do we need another book on human stem cell biology? The field is fairly long in the tooth now, thirteen years after Thomson first derived human embryonic stem (ES) cells (Thomson et al., 1998). There are many books that cover the theoretical aspects of the discipline (Oderico et al., 2004) and others that attempt to collate protocols useful to human stem cell biologists (Sullivan et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the new book Human Stem Cell Technology and Biology succeeds in combining both of these characteristics, providing not only a clear account of the scientific discoveries underpinning human stem cell biology, but also a useful range of laboratory protocols. The end product may be less comprehensive than Lanza’s classic text (Lanza et al., 2009), but it is perhaps more manageable and appropriate for a newcomer to the field or for an early career scientist working with human pluripotent cell lines for the first time.

Do we need another book on human stem cell biology? The field is fairly long in the tooth now, thirteen years after Thomson first derived human embryonic stem (ES) cells (Thomson et al., 1998). There are many books that cover the theoretical aspects of the discipline (Oderico et al., 2004) and others that attempt to collate protocols useful to human stem cell biologists (Sullivan et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the new book Human Stem Cell Technology and Biology succeeds in combining both of these characteristics, providing not only a clear account of the scientific discoveries underpinning human stem cell biology, but also a useful range of laboratory protocols. The end product may be less comprehensive than Lanza’s classic text (Lanza et al., 2009), but it is perhaps more manageable and appropriate for a newcomer to the field or for an early career scientist working with human pluripotent cell lines for the first time.