Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

Mutant Xist merely muffles X chromosome

In XX female mammals, inactivation of one X chromosome during development equalises the levels of X-linked gene products in females with those in males. Expression of the Xist gene from one of the two X chromosomes produces a non-coding RNA that coats and silences the chromosome from which it is transcribed. But how does Xist RNA induce chromosome silencing? XistIVS, an Xist mutant generated in mice by gene targeting, may help to answer this question, suggest Takashi Sado and co-workers (see p. 2649). In embryos carrying the XistIVS allele, they report, XistIVS is differentially upregulated, and its mutated transcript coats the X chromosome in cis in embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues, but X-inactivation is incomplete. This partial X-inactivation seems to be unstable, and the mutated X chromosome is reactivated in some extra-embryonic tissues and possibly in early epiblastic cells, suggesting that the RNA encoded by XistIVS is dysfunctional. Further studies of this unique mutation could thus reveal exactly how Xist RNA induces chromosome silencing.

In XX female mammals, inactivation of one X chromosome during development equalises the levels of X-linked gene products in females with those in males. Expression of the Xist gene from one of the two X chromosomes produces a non-coding RNA that coats and silences the chromosome from which it is transcribed. But how does Xist RNA induce chromosome silencing? XistIVS, an Xist mutant generated in mice by gene targeting, may help to answer this question, suggest Takashi Sado and co-workers (see p. 2649). In embryos carrying the XistIVS allele, they report, XistIVS is differentially upregulated, and its mutated transcript coats the X chromosome in cis in embryonic and extra-embryonic tissues, but X-inactivation is incomplete. This partial X-inactivation seems to be unstable, and the mutated X chromosome is reactivated in some extra-embryonic tissues and possibly in early epiblastic cells, suggesting that the RNA encoded by XistIVS is dysfunctional. Further studies of this unique mutation could thus reveal exactly how Xist RNA induces chromosome silencing.

It’s a wrap: Gpr126 and myelination

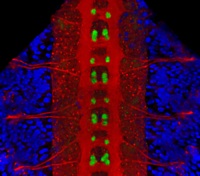

In the vertebrate peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells form the myelin sheath, the multilayered membrane that insulates axons and allows the rapid propagation of electrical signals. Now, on p. 2673, William Talbot and colleagues report that, as in zebrafish, the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr126 is essential for myelination and other aspects of peripheral nerve development in mammals. The researchers show that a mutation in Gpr126 causes a severe congenital hypomyelinating peripheral neuropathy in mice and reduces the expression of differentiated Schwann cell markers. In addition, Gpr126 mutant mice lack Remak bundles (the non-myelinating Schwann cells associated with small calibre axons), and exhibit delayed sorting of large calibre axons by Schwann cells, suggesting that the Schwann cells are arrested at the promyelinating stage. Finally, they report, Gpr126 mutant mice develop abnormalities in the perineurium (the connective tissue that surrounds each nerve fibre bundle). Given these results, the researchers suggest that Gpr126 might represent a target for the treatment of demyelinating diseases of nerves.

In the vertebrate peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells form the myelin sheath, the multilayered membrane that insulates axons and allows the rapid propagation of electrical signals. Now, on p. 2673, William Talbot and colleagues report that, as in zebrafish, the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr126 is essential for myelination and other aspects of peripheral nerve development in mammals. The researchers show that a mutation in Gpr126 causes a severe congenital hypomyelinating peripheral neuropathy in mice and reduces the expression of differentiated Schwann cell markers. In addition, Gpr126 mutant mice lack Remak bundles (the non-myelinating Schwann cells associated with small calibre axons), and exhibit delayed sorting of large calibre axons by Schwann cells, suggesting that the Schwann cells are arrested at the promyelinating stage. Finally, they report, Gpr126 mutant mice develop abnormalities in the perineurium (the connective tissue that surrounds each nerve fibre bundle). Given these results, the researchers suggest that Gpr126 might represent a target for the treatment of demyelinating diseases of nerves.

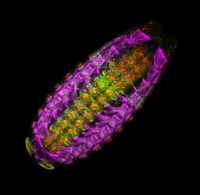

Production rates scale the Bicoid gradient

Embryonic patterning is insensitive to embryo size. Consequently, despite size variations among individuals in a population, their body parts are proportionate or ‘scaled’. But how is scaling achieved and do similar mechanisms control within-species and between-species scaling? On p. 2741, Jun Ma and colleagues use embryos from Drosophila melanogaster lines selected for large and small egg volumes to investigate the within-species scaling of the Bicoid (Bcd) morphogen gradient. They show that large embryos contain more maternal bcd mRNA than small embryos and, as a result, have higher anterior nuclear Bcd concentrations. This difference in the anterior production rate of Bcd leads to the scaling properties of the Bcd gradient. That is, in broad regions of large and small embryos, similar Bcd concentrations are found at the same relative embryonic positions. Thus, propose the researchers, unlike between-species scaling, which probably involves species-specific differences in Bcd diffusion and/or decay rates, within-species Bcd gradient scaling depends on the scaling of Bcd production rates with embryo volume.

Embryonic patterning is insensitive to embryo size. Consequently, despite size variations among individuals in a population, their body parts are proportionate or ‘scaled’. But how is scaling achieved and do similar mechanisms control within-species and between-species scaling? On p. 2741, Jun Ma and colleagues use embryos from Drosophila melanogaster lines selected for large and small egg volumes to investigate the within-species scaling of the Bicoid (Bcd) morphogen gradient. They show that large embryos contain more maternal bcd mRNA than small embryos and, as a result, have higher anterior nuclear Bcd concentrations. This difference in the anterior production rate of Bcd leads to the scaling properties of the Bcd gradient. That is, in broad regions of large and small embryos, similar Bcd concentrations are found at the same relative embryonic positions. Thus, propose the researchers, unlike between-species scaling, which probably involves species-specific differences in Bcd diffusion and/or decay rates, within-species Bcd gradient scaling depends on the scaling of Bcd production rates with embryo volume.

Plane speaking: the roles of Dachsous and Frizzled

In epithelial tissues, the polarisation of cells within the plane of the tissue helps to coordinate morphogenesis. The Dachsous (Ds) and Frizzled (Fz) signalling systems play key roles in establishing and maintaining this planar polarity but how these systems interact is unclear. Now, on p. 2751, Seth Donoughe and Stephen DiNardo report that the ds and fz genes contribute separately to planar polarity in the Drosophila ventral epidermis. The cuticle of fly larvae is covered with denticles, protrusions that help the larvae move. To investigate how this polarised pattern of denticles is established, the researchers developed a semi-automated method that measures the orientation of individual denticles in the ventral epidermis. Their analyses of various mutants show that ds and fz contribute independently to polarity, that they act over spatially distinct domains, and that the Ds but not the Fz system polarises tissue equally well across small and large field sizes. These and other results provide new insights into the planar polarity machinery.

In epithelial tissues, the polarisation of cells within the plane of the tissue helps to coordinate morphogenesis. The Dachsous (Ds) and Frizzled (Fz) signalling systems play key roles in establishing and maintaining this planar polarity but how these systems interact is unclear. Now, on p. 2751, Seth Donoughe and Stephen DiNardo report that the ds and fz genes contribute separately to planar polarity in the Drosophila ventral epidermis. The cuticle of fly larvae is covered with denticles, protrusions that help the larvae move. To investigate how this polarised pattern of denticles is established, the researchers developed a semi-automated method that measures the orientation of individual denticles in the ventral epidermis. Their analyses of various mutants show that ds and fz contribute independently to polarity, that they act over spatially distinct domains, and that the Ds but not the Fz system polarises tissue equally well across small and large field sizes. These and other results provide new insights into the planar polarity machinery.

LMO4: a co-activator of neurogenin 2 in the CNS

Numerous transcription factors regulate the generation and migration of neurons during the development of the central nervous system but the co-factors that support their activity remain unclear. Here (p. 2823), Soo-Kyung Lee and co-workers identify the LIM-only protein LMO4 as a co-activator of the proneural transcription factor neurogenin 2 (NGN2) in the developing mouse cortex. The researchers show that LMO4 and its binding partner nuclear LIM interactor (NLI) form a multi-protein transcription complex with NGN2. This complex, they report, is recruited to the E-box-containing enhancers of NGN2 target genes, which regulate various aspects of cortical development, and activates NGN2-mediated transcription. Consistent with this finding, the researchers demonstrate that neuronal differentiation is impaired in the cortex of Lmo4-null embryos, whereas expression of LMO4 facilitates NGN2-mediated migration and differentiation of neurons in the embryonic cortex. These results suggest that the LMO4:NLI module promotes the acquisition of cortical neuronal identities by forming a complex with NGN2 and subsequently activating NGN2-dependent gene expression.

Numerous transcription factors regulate the generation and migration of neurons during the development of the central nervous system but the co-factors that support their activity remain unclear. Here (p. 2823), Soo-Kyung Lee and co-workers identify the LIM-only protein LMO4 as a co-activator of the proneural transcription factor neurogenin 2 (NGN2) in the developing mouse cortex. The researchers show that LMO4 and its binding partner nuclear LIM interactor (NLI) form a multi-protein transcription complex with NGN2. This complex, they report, is recruited to the E-box-containing enhancers of NGN2 target genes, which regulate various aspects of cortical development, and activates NGN2-mediated transcription. Consistent with this finding, the researchers demonstrate that neuronal differentiation is impaired in the cortex of Lmo4-null embryos, whereas expression of LMO4 facilitates NGN2-mediated migration and differentiation of neurons in the embryonic cortex. These results suggest that the LMO4:NLI module promotes the acquisition of cortical neuronal identities by forming a complex with NGN2 and subsequently activating NGN2-dependent gene expression.

First blood: in vitro haematopoiesis

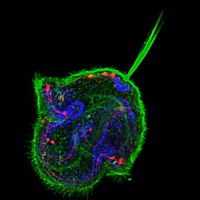

The conversion of embryonic stem (ES) cells into haematopoietic precursors in vitro could have important clinical applications, but strategies that achieve this feat usually require the use of feeder cells or serum. Now, Po-Min Chiang and Philip Wong describe a method for converting murine ES cells into endothelial cells and blood precursors at low cell densities in a serum-free defined medium (see p. 2833). The researchers identify a set of cytokines and small molecules that are necessary and sufficient to convert ES cells into definitive haematopoietic precursors within 6 days, and by tracking the fate of single progenitors with time-lapse video microscopy they follow this stepwise differentiation process. The determination of haemogenic fate, they report, occurs as early as day 4 of this differentiation protocol. Moreover, BMP4 plays essential time-sensitive roles in both angiogenesis and haemogenesis. This protocol, the researchers suggest, could thus serve as a framework for future studies of human haematopoiesis and for the development of treatments for haematopoietic disorders.

The conversion of embryonic stem (ES) cells into haematopoietic precursors in vitro could have important clinical applications, but strategies that achieve this feat usually require the use of feeder cells or serum. Now, Po-Min Chiang and Philip Wong describe a method for converting murine ES cells into endothelial cells and blood precursors at low cell densities in a serum-free defined medium (see p. 2833). The researchers identify a set of cytokines and small molecules that are necessary and sufficient to convert ES cells into definitive haematopoietic precursors within 6 days, and by tracking the fate of single progenitors with time-lapse video microscopy they follow this stepwise differentiation process. The determination of haemogenic fate, they report, occurs as early as day 4 of this differentiation protocol. Moreover, BMP4 plays essential time-sensitive roles in both angiogenesis and haemogenesis. This protocol, the researchers suggest, could thus serve as a framework for future studies of human haematopoiesis and for the development of treatments for haematopoietic disorders.

Plus…

As part of the Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology series, David McClay introduces the sea urchins and discuss how studies of sea urchins have contributed significantly to our understanding of the developmental mechanisms used to build a deuterstome organism.

See the Primer article on p. 2639

The recent Keystone Symposium on Evolutionary Developmental Biology presented an opportunity to showcase the latest research findings in this multidisciplinary field and, as reviewed by Haag and Lenski, revealed a growing relevance of this research to both basic and biomedical biology.

See the Meeting Review on p. 2633

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

Tags: Bicoid, Dachsous, echinoderm, evo devo, Frizzled, Grp126, haematopoiesis, LMO4, myelination, neurogenin 2, schwann cell, see urchin, stem cell, X inactivation, Xist

Categories: Research

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) (3 votes)

(3 votes)

In XX female mammals, inactivation of one X chromosome during development equalises the levels of X-linked gene products in females with those in males. Expression of the Xist gene from one of the two X chromosomes produces a non-coding RNA that coats and silences the chromosome from which it is transcribed. But how does Xist RNA induce chromosome silencing? XistIVS, an Xist mutant generated in mice by gene targeting, may help to answer this question, suggest Takashi Sado and co-workers (see p.

In XX female mammals, inactivation of one X chromosome during development equalises the levels of X-linked gene products in females with those in males. Expression of the Xist gene from one of the two X chromosomes produces a non-coding RNA that coats and silences the chromosome from which it is transcribed. But how does Xist RNA induce chromosome silencing? XistIVS, an Xist mutant generated in mice by gene targeting, may help to answer this question, suggest Takashi Sado and co-workers (see p.  In the vertebrate peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells form the myelin sheath, the multilayered membrane that insulates axons and allows the rapid propagation of electrical signals. Now, on p.

In the vertebrate peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells form the myelin sheath, the multilayered membrane that insulates axons and allows the rapid propagation of electrical signals. Now, on p.  Embryonic patterning is insensitive to embryo size. Consequently, despite size variations among individuals in a population, their body parts are proportionate or ‘scaled’. But how is scaling achieved and do similar mechanisms control within-species and between-species scaling? On p.

Embryonic patterning is insensitive to embryo size. Consequently, despite size variations among individuals in a population, their body parts are proportionate or ‘scaled’. But how is scaling achieved and do similar mechanisms control within-species and between-species scaling? On p.  In epithelial tissues, the polarisation of cells within the plane of the tissue helps to coordinate morphogenesis. The Dachsous (Ds) and Frizzled (Fz) signalling systems play key roles in establishing and maintaining this planar polarity but how these systems interact is unclear. Now, on p.

In epithelial tissues, the polarisation of cells within the plane of the tissue helps to coordinate morphogenesis. The Dachsous (Ds) and Frizzled (Fz) signalling systems play key roles in establishing and maintaining this planar polarity but how these systems interact is unclear. Now, on p.  Numerous transcription factors regulate the generation and migration of neurons during the development of the central nervous system but the co-factors that support their activity remain unclear. Here (p.

Numerous transcription factors regulate the generation and migration of neurons during the development of the central nervous system but the co-factors that support their activity remain unclear. Here (p.  The conversion of embryonic stem (ES) cells into haematopoietic precursors in vitro could have important clinical applications, but strategies that achieve this feat usually require the use of feeder cells or serum. Now, Po-Min Chiang and Philip Wong describe a method for converting murine ES cells into endothelial cells and blood precursors at low cell densities in a serum-free defined medium (see p.

The conversion of embryonic stem (ES) cells into haematopoietic precursors in vitro could have important clinical applications, but strategies that achieve this feat usually require the use of feeder cells or serum. Now, Po-Min Chiang and Philip Wong describe a method for converting murine ES cells into endothelial cells and blood precursors at low cell densities in a serum-free defined medium (see p.