A regeneration retrospective: time heals all wounds

Posted by Alex Eve, on 5 September 2023

This post is part of the regeneration retrospective series.

Wound healing is a crucial process in both regenerating and non-regenerating tissues. In addition to restoring the biological function of a tissue by removing damaged cells and reconstituting a continuous epithelium, the response to a wound can determine whether a pro-regenerative environment is provided (e.g. a blastema) or, alternatively, induce the formation of a fibrotic (and sometimes pathogenic) scar through the deposition of extracellular matrix (Wong and Whited, 2020). In this third episode, I discuss the highlights from the following two articles:

Wound Contraction in Relation to Collagen Formation in Scorbutic Guinea-pigs

M. Abercrombie, M. H. Flint and D. W. James

https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.4.2.167

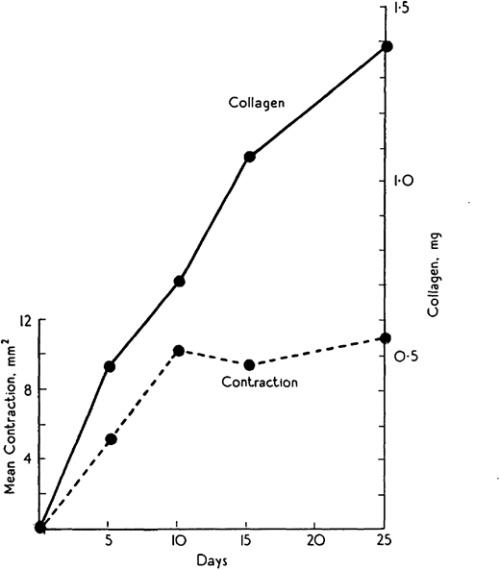

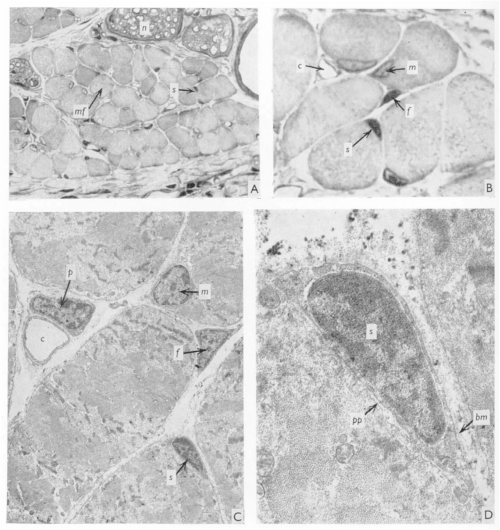

Michael Abercrombie was a prominent English cell biologist who’s credited with early science public engagement by writing biology books for The People with popular publisher, Penguin. Michael’s co-authors for this paper are somewhat more elusive, but together, Abercrombie, Flint and James seemed to have a penchant for tattooing rodents. Their 1956 JEEM/Development publication follows an earlier paper from the same authors, published in the same journal, describing the purse string-like contraction of rat skin following wounding and the increase of extracellular matrix protein, collagen, in scabs during the healing process (Fig. 1; Abercrombie et al., 1954). In their follow-up piece, at a time when one could publish a paper containing no figures or tables whatsoever(!), Abercrombie and colleagues turn their tattoo needles towards male guinea pigs (although I’m unsure why rats were abandoned) to further characterise the role of collagen. Abercrombie, Flint and James set up an experiment in which their guinea pigs were fed a vitamin C-deficient diet, based on the knowledge that vitamin C is needed for collagen synthesis (Wolbach and Bessey, 1942), with a control group provided with a vitamin C supplement. After injuring the skin of the guineas and using tattoos to trace skin deformation as it healed, they showed that, while wound contraction was unaffected, vitamin C-deficient animals had smaller, fragile scabs that contained less collagen as determined by measuring hydroxyproline as a proxy (Abercrombie et al., 1956). These results were able to uncouple the possible roles of collagen in wound closure versus scarring, and led the way for future research to focus on a cell-based – rather than matrix-based – mechanism of epidermal contraction.

Almost 70 years later, collagen is still an important focus in the regeneration community. The wound-healing process of many other organs, in addition to the skin, has been studied. The number of experiments using guinea pigs dropped considerably, but are starting to reemerge, particularly in the field of endometrium regeneration. Instead, the lab staples, mice and Drosophila, are a common mammalian model for, well, just about everything and the relatively young lab species, the zebrafish, has gained prominence, due to its ability to regenerate the heart (Simões and Riley, 2022) and spinal cord (Becker and Becker, 2022). Focus has turned less towards the exact role of collagen and more towards the cells that secrete it and, importantly, whether this secretion can be regulated in a way that promotes regeneration and prevents scarring with important therapeutic implications. Among these recent studies, the process of inflammation and the role of immune cells during wound healing and regeneration has gained attention (Ginhoux and Martin, 2022). However, tattooing, it seems, has been lost from many a materials and methods section.

Macrophages directly contribute collagen to scar formation during zebrafish heart regeneration and mouse heart repair

Filipa C. Simões, Thomas J. Cahill, Amy Kenyon, Daria Gavriouchkina, Joaquim M. Vieira, Xin Sun, Daniela Pezzolla, Christophe Ravaud, Eva Masmanian, Michael Weinberger, Sarah Mayes, Madeleine E. Lemieux, Damien N. Barnette, Mala Gunadasa-Rohling, Ruth M. Williams, David R. Greaves, Le A. Trinh, Scott E. Fraser, Sarah L. Dallas, Robin P. Choudhury, Tatjana Sauka-Spengler and Paul R. Riley

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14263-2

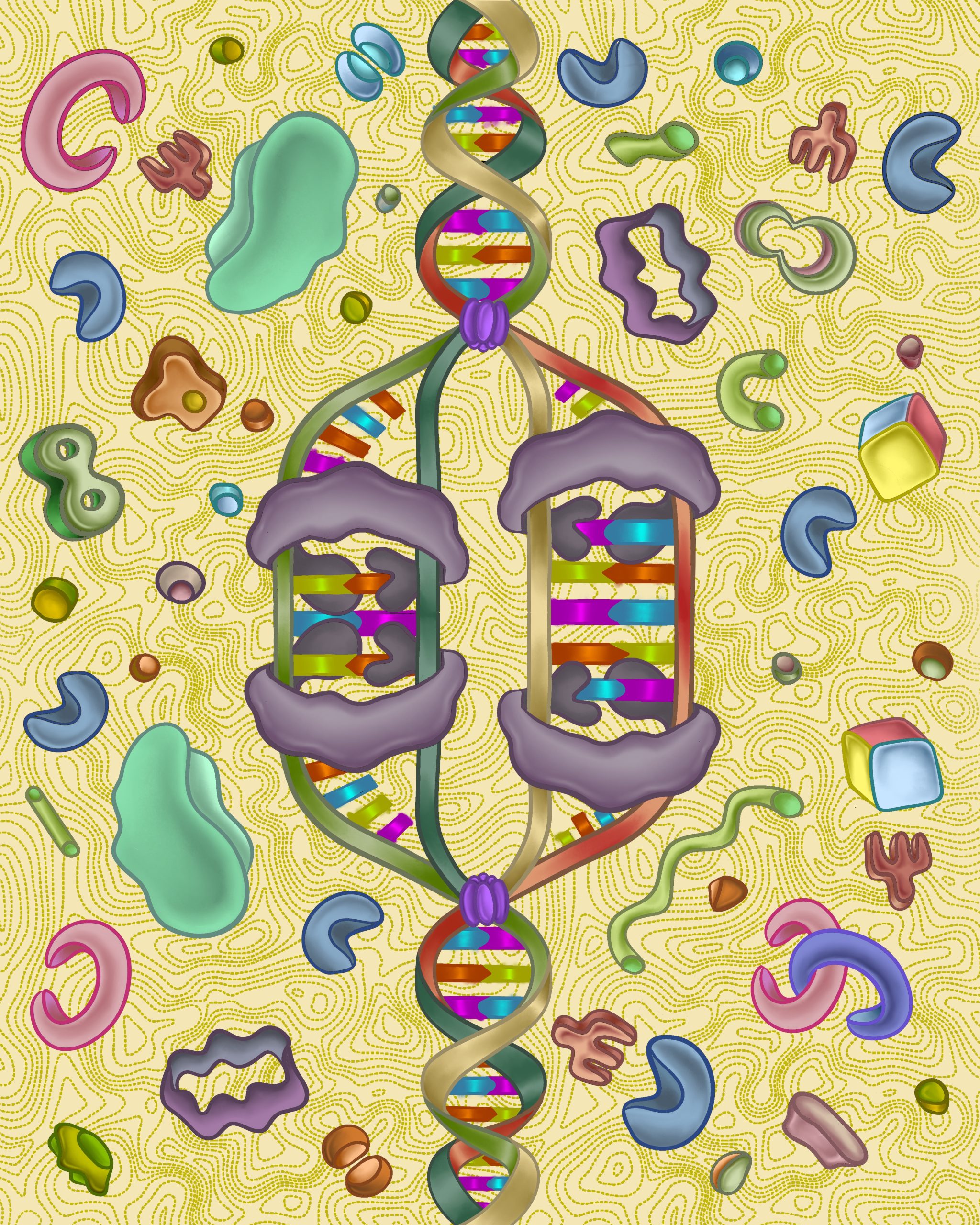

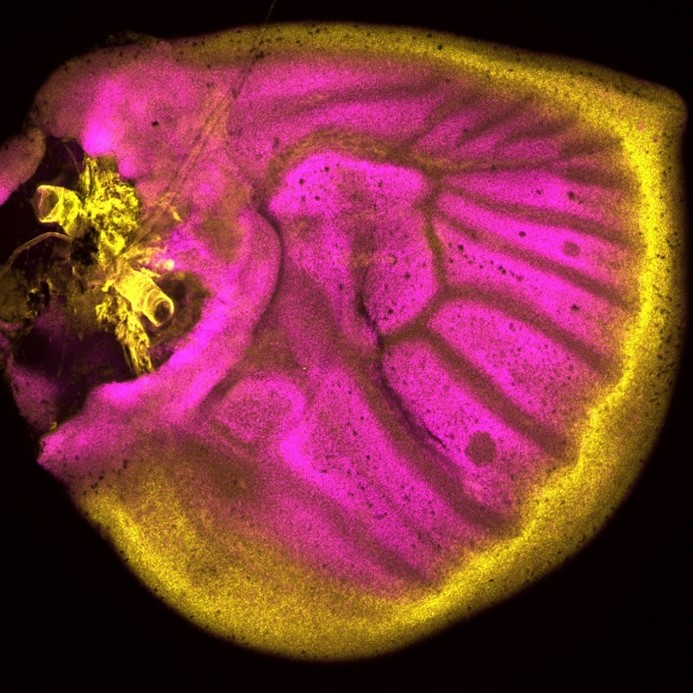

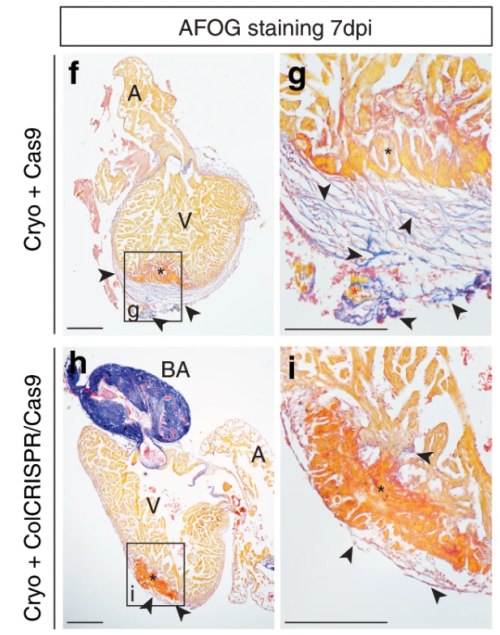

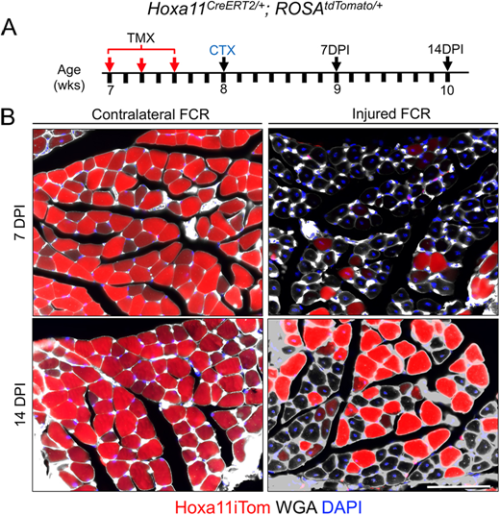

Simões (University of Oxford) and colleagues’ paper, published in Nature Communications in 2020, challenges previous assumptions in the field that immune cells only stimulate fibroblasts to deposit collagen during cardiac wound healing. It’s chock-full of figures and data – in stark contrast to Abercrombie and pals – and they use a vast array of sophisticated genetic techniques, including transgenic transplants and cell-specific knockouts in both neonatal (regenerative) and adult mice, as well as zebrafish, along with imaging and next-generation sequencing (Simões et al., 2020). The authors perform transcriptome analyses of macrophages to show that they have distinct responses to wounds depending on the type (e.g. resection vs. cryoinjury in zebrafish) and the age of the animal (e.g. neonate vs. adult mice). In addition, in the unregenerative adult mouse and zebrafish cryoinjury conditions, macrophages express collagen. Using fluorescently tagged collagen constructs, the authors show that adult macrophages directly contribute collagen to the scar. Supporting this, the transplant of adult macrophages into neonates induces ectopic scarring during cardiac healing. Importantly, the genetic knockdown of collagen genes in zebrafish macrophages is sufficient to significantly reduce scar formation in the heart following cryoinjury, potentially providing a permissive environment for cardiac regeneration (Fig. 2). This work from Simões and colleagues posit macrophages as a direct source of collagen during scarring and provides a future avenue for therapeutic treatment of heart damage.

Both these papers are interested in understanding collagen during wound healing. Abercrombie, Flint and James, determine that collagen is dispensable for skin wound contraction, but not for scab formation, while Simões and colleagues reveal macrophages as an unlikely source for collagen deposition in the mammalian heart. Tomorrow, we turn our heads (or tails) towards an excellent demonstration of epimorphic regeneration.

References

M. Abercrombie, M. H. Flint, D. W. James; Collagen Formation and Wound Contraction during Repair of Small Excised Wounds in the Skin of Rats. Development 1 September 1954; 2 (3): 264–274. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.2.3.264

Thomas Becker, Catherina G. Becker; Regenerative neurogenesis: the integration of developmental, physiological and immune signals. Development 15 April 2022; 149 (8): dev199907. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.199907

Florent Ginhoux, Paul Martin; Insights into the role of immune cells in development and regeneration. Development 15 April 2022; 149 (8): dev200829. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.200829

Filipa C. Simões, T. J. Cahill, A. Kenyon et al. Macrophages directly contribute collagen to scar formation during zebrafish heart regeneration and mouse heart repair. Nat Commun 2020; 11, 600. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14263-2

Filipa C. Simões, Paul R. Riley; Immune cells in cardiac repair and regeneration. Development 15 April 2022; 149 (8): dev199906. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.199906

S. B. Wolbach, O.A. Bessey. Tissue changes in vitamin deficiencies. Physiol. Rev. 22, 1942; 233–89. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1942.22.3.233

Alan Y. Wong, Jessica L. Whited; Parallels between wound healing, epimorphic regeneration and solid tumors. Development 1 January 2020; 147 (1): dev181636. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.181636

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(2 votes)

(2 votes)