This interview first featured in Development.

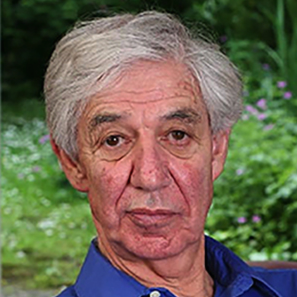

Didier Stainier is a Principal Investigator at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research in Bad Nauheim, Germany. Having spent most of his career in the USA using zebrafish to study organ development, Didier recently moved back to Europe and is now branching out to study organ development in mice. At a recent conference, we caught up with Didier and asked him about his career, his thoughts on funding, view on morpholinos and his advice for young researchers.

What first got you interested in developmental biology and was there anyone in particular who inspired you?

What first got you interested in developmental biology and was there anyone in particular who inspired you?

When I was young, my mother worked in the Zoology Department at the University of Liège, Belgium, and when she was busy at work we would often go to the department museum. So I spent a lot of time there. At that time, my dad was also working in a lab – he trained in the Pharmacy Department where his father was a professor. Most of my extended family was actually in the medical field, practicing as doctors or pharmacists, so science was a major part of my environment growing up. Then, when I was 15, I moved to the UK, actually to Wales. I studied at the United World College of the Atlantic, and there I had a very inspiring biology professor called Alan Hall. He was a somewhat quirky, Cambridge-educated fellow who was a most enthusiastic and committed teacher. I then went back to Liège for university, but essentially this was not very satisfying as the biology textbooks we were using there were older than those I had used in high school in Wales. I also wanted to start doing research during my undergraduate studies and in Belgium, at the time, this wasn’t possible until the masters level. So, I transferred to the USA. There I worked in an immunology lab at Brandeis University and took a developmental neurobiology course with Eve Marder, who was my academic advisor. From there, I moved to Harvard for my graduate studies, where Doug Melton had recently arrived. I did several lab rotations – my first was actually with Doug – and eventually joined Wally Gilbert’s lab to work in developmental neurobiology.

How, why and when did you start working with zebrafish?

When I joined his lab, Wally had just come back to Harvard from Biogen and was starting some new projects. His lab was very eclectic: there was the sequencing technology subgroup, the origin of introns subgroup and the immunology subgroup. As you might imagine, Wally was a very inspiring person – he’s probably the person who shaped me the most scientifically. One of the projects that he wanted to start was to look for cell surface molecules involved in axon guidance and target recognition in the developing mouse brain, and I thought that this would be a very interesting project to take on. A couple of years later, a psychiatry fellow came to the lab and set up the zebrafish model with the goal of developing insertional mutagenesis techniques. Although I did not work with fish in Wally’s lab, I was of course exposed to them and so they were very much on my mind when I was looking for a post-doc position in 1989. One of the people I applied to work with was Mark Fishman, who’d just received a large chunk of money to set up a cardiovascular research centre at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. We discussed the possibility of doing some zebrafish work and, shortly thereafter, he asked me to get a zebrafish heart project off the ground and then put some major resources into it. He also recruited Wolfgang Driever as a junior faculty member to the centre; Wolfgang had recently finished his PhD with Jani (Christiane) Nüsslein-Volhard, in Tübingen, Germany, and so had also been exposed to zebrafish. Wolfgang first went to Eugene, Oregon, for several months to train with Monte Westerfield, Chuck Kimmel and Judith Eisen, and during that time Mike Pack and I got started with a few tanks on a bench. Wolfgang then came back from Eugene to start his own lab, we moved to a new building and set up the first fish room, and things really took off from there.

How did the big zebrafish screen, which was published as a Special Issue of Development in 1996, come about?

Well, many of us wanted to do genetic screens; one of the reasons Mark and I wanted to work with zebrafish was to be able to carry out a screen for heart mutants, and Wolfgang, of course, also wanted to do screens. Thus, there was some prior arrangement to decide who would ultimately focus on specific developmental processes and follow up on the mutants relevant to these processes, but it really was a team effort. There were many interesting characters in the team, several of whom have become very prominent in the field. We certainly learnt a lot from each other and it was a very productive period. The large screen taking place in parallel in Jani’s lab at the time also added to the excitement, and it was Jani who suggested and coordinated the Development Zebrafish Special Issue. The Special Issue was a great opportunity to present our work, although much of the writing was done without me – at that time, communication was not as easy as it is now – as I had left to set up my own lab at UCSF in 1995. One also has to remember all the pioneering work done in Eugene, as it played a major role in attracting people into the zebrafish field. In addition, many people, including myself, spent time in Eugene learning how to work with zebrafish.

Recent advances in genome engineering have raised lots of debate about the use of morpholinos – in both zebrafish and other model organisms – with regards to how and when they should be used and whether they’re actually reliable. I know you have commented on this in a few recent publications (Schulte-Merker and Stainier, 2014; Stainier et al., 2015; Rossi et al., 2015), but what are your thoughts on this now?

My thoughts, which I believe are shared by many others in the field, are that we need to keep an open mind as key data keep being generated. Taking extreme views one way or another is not good for the field. There are of course many potential reasons why antisense technology can lead to artefacts, and people need to be careful and aware of the various caveats of the tools they’re using. I try to see opportunities when others may see downsides and, if some of the observations that we have made recently turn out to be widely applicable, they should open the door to some very compelling biology. There might indeed be some interesting and intriguing reasons for the discrepancies between mutant and morphant phenotypes as we have seen evidence of genetic compensation in mutants but not in morphants. Getting to the root of these discrepancies and understanding the mechanisms underlying compensation will not be easy, but it will certainly be a worthwhile endeavour. We will try to pursue these issues but, regardless, I think that morpholinos, much like siRNAs and other antisense tools, are reagents that can give you valuable information if used with appropriate care and scepticism. Understanding all the effects morpholinos are causing inside a cell is also an important goal that will provide further clarity on what is clearly a complex situation.

I gather that you’re now starting some mouse-based studies, again carrying out forward genetic screens to identify new players in developmental process. What was the motivation behind this?

When I was thinking about moving the lab from UCSF to Germany, we held a lab retreat and I asked the students and postdocs what projects or kind of work they would like to tackle, setting financial limitations aside. About half the scientists mentioned that they would like to do some mouse work. At the time we were mostly working on zebrafish; we had some collaborations with mouse people but we weren’t doing any mouse work ourselves. However, several scientists, some of whom had come from mouse labs, thought that they would like to complement their zebrafish studies with mouse studies, and there were others who were getting reviews of their papers with requests for mouse data. Mouse work was also something that I wanted to get back to, having been an extensive part of my PhD, and I wanted to get a deeper understanding of the work that was going on in other vertebrate development labs. There were many reasons to move from the USA to Germany, but when you move to an institution like the Max Planck, it gives you the opportunity to think about projects that you would not otherwise be able to do.

And so we thought about the various types of screens that we wanted to carry out and the phenotypes we should be looking for and, given that zebrafish don’t have lungs and that the Max Planck Institute we were moving to is a heart and lung institute, we decided to focus on the respiratory system. The goal of our screen is to look for cell differentiation phenotypes in the lung and trachea, and we are starting to see some very interesting phenotypes, including some that should represent informative disease models. Importantly, now that the activation energy to work on mouse has been lowered substantially, several people in the lab are pursuing their own projects using both fish and mice.

During that big move from the USA to Germany, did you notice any obvious differences in lab culture or in the funding situation between the two countries?

There are various ways of funding scientific research around the world. At one end of the spectrum, one goes to a university or research institute, they give you a little start-up money and then expect you to come up with grant money to fund everything else. At the other end of the spectrum would be a Max Planck Institute, where the Max Planck Society provides substantial core funding. It’s a real privilege to be working in a Max Planck Institute. I appreciate that there are advantages to writing research proposals and grants, because it forces one to think carefully through every step of the project, but after a while this mode of thinking becomes automatic before starting up any new project. In terms of lab culture, I think that we’ve been able to maintain the same kind of culture and set-up that we had in the USA: a physically wide-open lab to stimulate communication with a mostly flat hierarchy.

What is your advice to young researchers today?

I would like to tell young researchers to follow their dreams of course, but I also want to stress that they need to reach out to society and inform them about the value of basic science as well as the value of working with model systems, even very basic model systems. In the USA, and in other countries, the emphasis – and hence the funding – is increasingly being placed on translational research. This switch in focus is one of the reasons I moved from the USA to Germany: I felt that, in order to keep running a lab in the USA investigating several different topics, I would have had to move to more translational work. I had a hard time imagining myself not being able to pursue the kind of basic research required for innovative translational work. I’d like to think that the tide will turn and that there will be renewed appreciation of seeking knowledge for the sake of knowledge itself, for one never really knows when a basic science finding will transform translational research – the CRISPR/Cas9 technology is just one recent example of such a transformative finding arising from basic science. In this context, I really appreciate the value that the Max Planck Society places on basic science.

What would people be surprised to find out about you?

Well, I played quite a bit of rugby when I was young, first in Belgium, then of course in Wales, and then when I went back to Belgium. Actually, just before I moved to the USA, I played very briefly on the Belgian national junior team. I also played with the Harvard Business School team when I was a graduate student at Harvard. Moving to San Francisco to set up my lab, and starting a family at the same time, brought an end to this hobby.

References:

Rossi, A., Kontarakis, Z., Gerri, C., Nolte, H., Hölper, S., Krüger, M. and Stainier, D. Y. (2015). Genetic compensation induced by deleterious mutations but not gene knockdowns. Nature 524, 230–233.doi:10.1038/nature14580

Schulte-Merker, S. and Stainier, D. Y. R. (2014). Out with the old, in with the new: reassessing morpholino knockdowns in light of genome editing technology. Development141, 3103–3104.doi:10.1242/dev.112003

Stainier, D. Y. R., Kontarakis, Z. and Rossi, A. (2015). Making sense of anti-sense data.Dev. Cell 12, 7–8.doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2014.12.012

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(3 votes)

(3 votes)

Didier Stainier is a Principal Investigator at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research in Bad Nauheim, Germany. Having spent most of his career in the USA using zebrafish to study organ development, Didier recently moved back to Europe and is now branching out to study organ development in mice. At a recent conference, we caught up with Didier and asked him about his career, his thoughts on funding, view on morpholinos and his advice for young researchers. See the Spotlight on p.

Didier Stainier is a Principal Investigator at the Max Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research in Bad Nauheim, Germany. Having spent most of his career in the USA using zebrafish to study organ development, Didier recently moved back to Europe and is now branching out to study organ development in mice. At a recent conference, we caught up with Didier and asked him about his career, his thoughts on funding, view on morpholinos and his advice for young researchers. See the Spotlight on p.  Neuromesodermal progenitors (NMps) contribute to both the elongating spinal cord and the adjacent paraxial mesoderm. It has been assumed that these cells arise as a result of anterior neural plate patterning. However, as the molecular mechanisms that specify NMps in vivo are uncovered, and as protocols for generating these bipotent cells from mouse and human pluripotent stem cells in vitro are established, the emerging data suggest that this view needs to be revised. See the Hypothesis by Storey et al on p.

Neuromesodermal progenitors (NMps) contribute to both the elongating spinal cord and the adjacent paraxial mesoderm. It has been assumed that these cells arise as a result of anterior neural plate patterning. However, as the molecular mechanisms that specify NMps in vivo are uncovered, and as protocols for generating these bipotent cells from mouse and human pluripotent stem cells in vitro are established, the emerging data suggest that this view needs to be revised. See the Hypothesis by Storey et al on p.  Polycomb and Trithorax group chromatin proteins play important roles promoting the stable and heritable repression and activation of gene expression, respectively. Here, Geisler and Paro review recent advances that have shed light on the mechanisms by which these two classes of proteins maintain epigenetic memory and allow dynamic switches in gene expression during development. See the Review on p.

Polycomb and Trithorax group chromatin proteins play important roles promoting the stable and heritable repression and activation of gene expression, respectively. Here, Geisler and Paro review recent advances that have shed light on the mechanisms by which these two classes of proteins maintain epigenetic memory and allow dynamic switches in gene expression during development. See the Review on p.  (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

– We reposted two interviews originally published in Development:

– We reposted two interviews originally published in Development:

(45 votes)

(45 votes)