Post-Doc position in models of pattern formation and morphogenesis

Posted by gneifd, on 11 November 2014

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Post-Doc position in models of pattern formation and morphogenesis

1.Job/ project description:

The main objective is to:

a) Develop mathematical models of organ development (starting with but no restricted to teeth, hair and wings). The mathematical models include intracellular gene networks, cell signalling and extra-cellular signal diffusion, bio-mechanical interactions between large

collectives of cells (all in 3D) (see above publications for orientative examples)

b) Develop models about the evolution of gene networks and embryonic development.

Our aims and research is devoted to understand how animal structure and morphology arises during the process of develpment by interactions between genes, cells and tissues. This is certainly a very complex process that involves many different kinds of interactions happening in complex spatio-temporal settings. Mathematical models are a good way to integrate this complexity to try to understand the biological logic of how animals transform from simple oocytes to animals that are functional and architecturally complex.

Our models take as inputs known or estimated gene networks and the initial distribution of cells in space (in a given stage in development) and provide as a result the final organ morphology and patterns of gene expression in a given organ (in a given, latter, stage of development). Each model is simply a mathematical implementation of a hypothesis about how an organ develops. We construct these hypotheses, based on experimental work from collaborating groups, and implement them in a computational model. The advantage of computational models in respect to merely verbal arguments is that the models provide precise quantitative predictions that are more easily to unambigously compare with experimental results (from new experiments aimed at testing the hypothesis). Merely verbal arguments are more difficult to be proven wrong or right and get even difficult to express when the process under study involves a large number of cells in complex movement and communication between them (as it is often the case in development). These easily lead to largely unintuitive dynamics that are hard to analyze without quantitative models.

In addition, computational models allow to explore not only the wild-type but also, by variaton in the underlying gene network, the range of possible morphological variants (and how they change through development). The capacity to play with the parameters of the model allows us to actually understand its dynamics.

Ultimately, a model is simply a summary of what we think we understand about a system but that allows us to see if the underlying hypothesis could work. That the model works does not imply that the hypothesis is right, further experiments are required, but if the model can not produce the right wild-type it means that the underlying hypothesis is wrong or incomplete. In other words, what we thought we understood, we did not actually understand.

The biotechnology institute includes a range of experimental biologitst working on several systems. The supervisor will be Dr. Salazar-Ciudad but the PhD would include close collaboration with Jukka Jernvall group and would include collaboration with other developmental biologists in the center. In addition, Jernvall’s group includes bioinformaticians, morphometricians, paleontologists and other evolutionary and

systems biologists (in addition to developmental biologists). The work may also include, optionally, collaboration, and spending some time, in Barcelona.

The modeling can focus on gene network regulation, cell-cell communication, cell mechanical interactions and developmental

mechanisms in general and, optionally, artifical in silico evolution.

2. Requirements:

The applicant should be a biologists, or similar, preferably with a strong background in either evolutionary biology, developmental biology or

theoretical biology. Some knowledge of ecology, zoology, cell and molecular biology are also desirable.

Bioinformaticians, systems biologists or computer biologists that do not have a degree in biology or similar similar would not be considered

(this excludes computer scientists, physicists and engineers).

Programming skills or a willingness to acquire them is required.

The most important requirement is a strong interest and motivation on science, gene networks and evolution. A capacity for creative and

critical thinking is also desirable.

3. Description of the position:

The fellowship will be for a period of 2 years (100% research work: no teaching involved) extendable to 2 more years.

Salary according to Finnish post-doc salaries.

4. The application must include:

-Application letter including a statement of interests

-CV (summarizing degrees obtained, subjects included in degree and

grades, average grade)

-Application should be send to Isaac Salazar-Ciudad by email:

isaac.salazar@helsinki.fi

Foreign applicants are advised to attach an explanation of their University’s grading system. Please remember that all documents should

be in English (no official translation is required)

5. Examples of recent publications by Isaac Salazar-Ciudad group.

-Salazar-Ciudad I1, Marín-Riera M. Adaptive dynamics under

development-based genotype-phenotype maps.

Nature. 2013 May 16;497(7449):361-4.

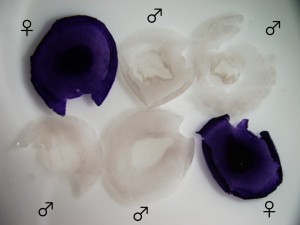

-Salazar-Ciudad I, Jernvall J. A computational model of teeth and

the developmental origins of morphological variation. Nature. 2010

Mar 25;464(7288):583-6.

6. Interested candidates should check our group webpage:

http://www.biocenter.helsinki.fi/salazar/index.html

The deadline is 15 of August (although candidates may be selected before).

Isaac Salazar-Ciudad: isaac.salazar@helsinki.fi

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

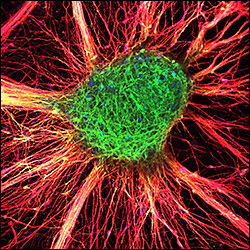

Malin Parmar heads a research group focused on developmental and regenerative neurobiology at Lund University in Sweden. The ultimate goal of her research is to develop cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease.

Malin Parmar heads a research group focused on developmental and regenerative neurobiology at Lund University in Sweden. The ultimate goal of her research is to develop cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease.

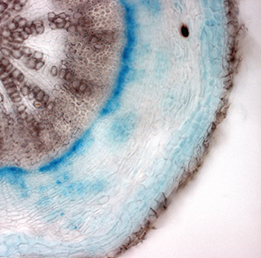

Class I KNOX transcription factors, such as SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM) and KNAT1, are known to play a role in the plant shoot apical meristem (SAM), where they are thought to prevent differentiation and hence promote stem cell maintenance. Now, on p.

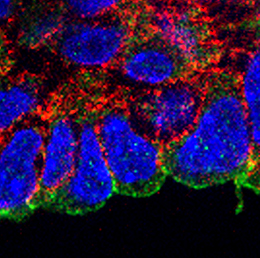

Class I KNOX transcription factors, such as SHOOT MERISTEMLESS (STM) and KNAT1, are known to play a role in the plant shoot apical meristem (SAM), where they are thought to prevent differentiation and hence promote stem cell maintenance. Now, on p.  During its development, the heart tube undergoes rapid elongation, fuelled by the addition of cardiac progenitors from the second heart field (SHF). The gene regulatory networks governing SHF formation have been studied extensively, but little is known about the basic cellular features of SHF cells. Now, Robert Kelly and co-workers show that the transcription factor TBX1, which is implicated in both normal SHF development and congenital heart defects, regulates the epithelial properties of mouse SHF cells (p.

During its development, the heart tube undergoes rapid elongation, fuelled by the addition of cardiac progenitors from the second heart field (SHF). The gene regulatory networks governing SHF formation have been studied extensively, but little is known about the basic cellular features of SHF cells. Now, Robert Kelly and co-workers show that the transcription factor TBX1, which is implicated in both normal SHF development and congenital heart defects, regulates the epithelial properties of mouse SHF cells (p.  During development, neuromesodermal (NM) stem cells give rise to both neural cells and paraxial presomitic mesoderm (PSM) cells, but what dictates PSM fate? Here, Terry Yamaguchi and colleagues show that a single transcription factor – mesogenin 1 (Msgn1) – acts as a master regulator of PSM development (p.

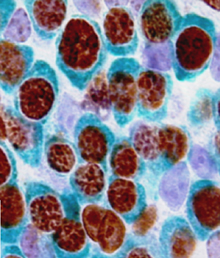

During development, neuromesodermal (NM) stem cells give rise to both neural cells and paraxial presomitic mesoderm (PSM) cells, but what dictates PSM fate? Here, Terry Yamaguchi and colleagues show that a single transcription factor – mesogenin 1 (Msgn1) – acts as a master regulator of PSM development (p.  Embryonic germ cells display strikingly different fates with regard to mitosis and meiosis, depending on their sex. In female mice, germ cells switch from mitosis to meiosis shortly after reaching the foetal gonad where they generate the lifelong pool of oocytes. However, in males, meiosis and mitosis are actively repressed, and germ cells remain quiescent in the gonad until birth, when they resume mitosis and start generating spermatocytes. Here (p.

Embryonic germ cells display strikingly different fates with regard to mitosis and meiosis, depending on their sex. In female mice, germ cells switch from mitosis to meiosis shortly after reaching the foetal gonad where they generate the lifelong pool of oocytes. However, in males, meiosis and mitosis are actively repressed, and germ cells remain quiescent in the gonad until birth, when they resume mitosis and start generating spermatocytes. Here (p.  One of the first patterning events of embryogenesis occurs during gastrulation: three-dimensional (3D) cell movements reorganise the embryo, a mass of morphologically similar cells, into an axially organised structure with three germinal layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm). To date, two-dimensional (2D) culture models have failed to recapitulate such complex cell behaviours linking cell movement to cell fate. Here (p.

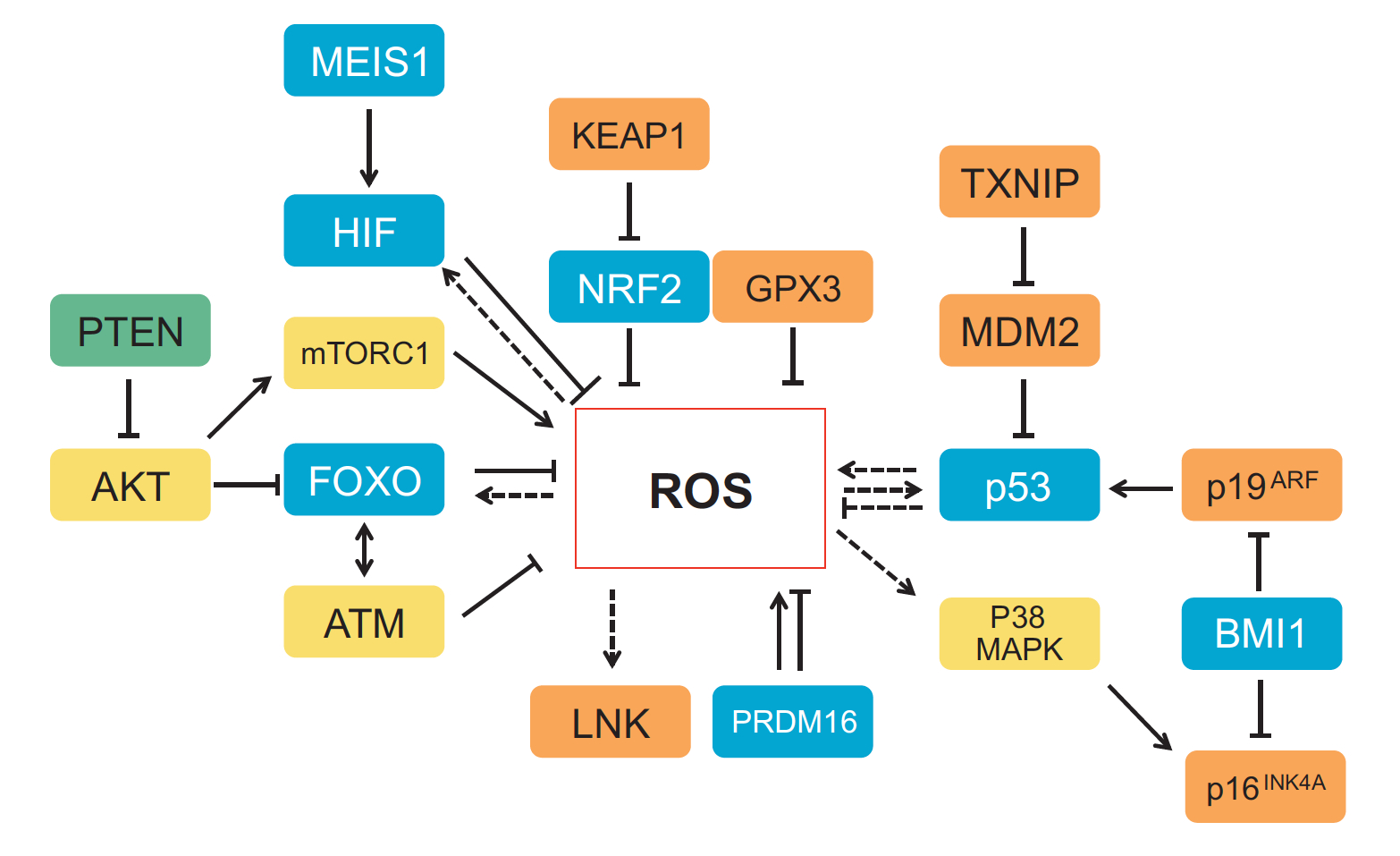

One of the first patterning events of embryogenesis occurs during gastrulation: three-dimensional (3D) cell movements reorganise the embryo, a mass of morphologically similar cells, into an axially organised structure with three germinal layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm). To date, two-dimensional (2D) culture models have failed to recapitulate such complex cell behaviours linking cell movement to cell fate. Here (p.  Recent work suggests that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can influence stem cell homeostasis and lineage commitment. In this Primer, Ghaffari and colleagues provide an overview of ROS signalling and its impact on stem cells, reprogramming and ageing. See the Primer on p.

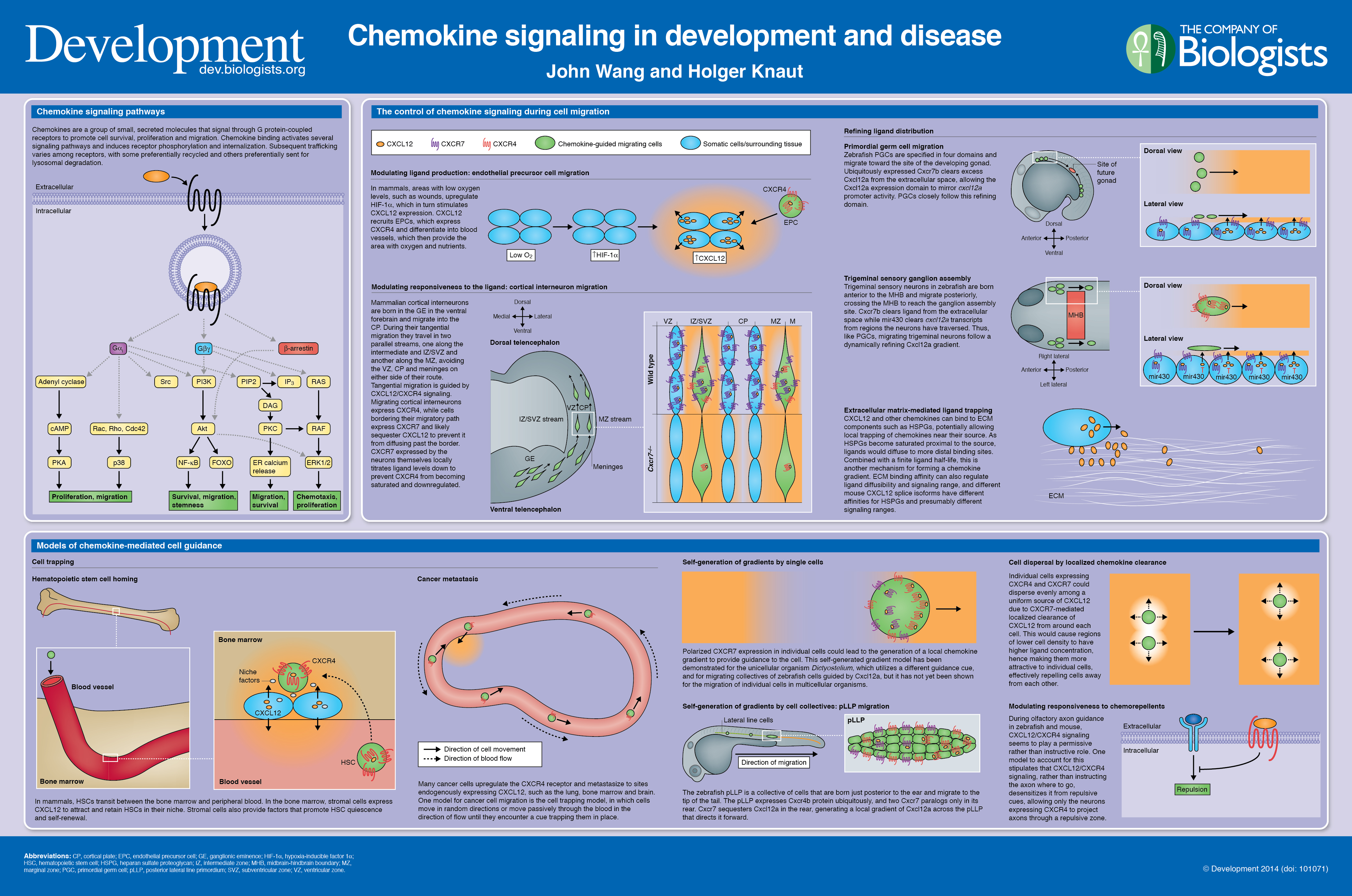

Recent work suggests that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can influence stem cell homeostasis and lineage commitment. In this Primer, Ghaffari and colleagues provide an overview of ROS signalling and its impact on stem cells, reprogramming and ageing. See the Primer on p.  In our latest poster and companion article, Wang and Knaut provide an overview of chemokine signalling and some the chemokine-dependent strategies used to guide migrating cells. See the poster on p.

In our latest poster and companion article, Wang and Knaut provide an overview of chemokine signalling and some the chemokine-dependent strategies used to guide migrating cells. See the poster on p.  The development of plant leaves follows a common basic program, which can be modulated to generate a diverse range of leaf forms. Bar and Ori review recent work examining how plant hormones, transcription factors and tissue mechanics influence leaf development. See the Review on p.

The development of plant leaves follows a common basic program, which can be modulated to generate a diverse range of leaf forms. Bar and Ori review recent work examining how plant hormones, transcription factors and tissue mechanics influence leaf development. See the Review on p.