I am a former diploma student in Emmanuel Farge’s team “Mechanics and genetics of embryonic and tumoral development” (Paris). Watching embryos could only convince me of Lewis Wolpert’s famous claim that “gastrulation is the most important time in your life” – but I also think we should keep in mind Theodosius Dobzhansky’s statement that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”. Hence, the evolution of gastrulation should be an especially important topic. In this post, I hope to share the excitement we got at trying to untangle some of its mysteries.

According to Plato, the universe was necessarily a sphere – as this was the most perfect of all possible shapes. When it came to creating people, Plato’s Creator was similarly well-intended, and first made us ball-shaped; but it was quickly obvious that spherical people were suboptimal, as they wouldn’t stop tumbling around. In an unusually self-critical move for a divine being, Plato’s creator added legs and arms on second thought, so that early humans would not be bound to passively follow gravity but could “get over high places and get out of deep ones”.

We share with Plato’s people the fact that we started as spheres. One of the first achievements of developmental biology was to demonstrate that all animals come from ball-shaped eggs (either spherical or, in the fanciest cases, looking like roughly rugby ball-shaped ellipsoids). The first cell divisions cleave the egg into multiple cells, but don’t alter the overall form. This ball shape is only lost when the first cell movements start deforming the embryo, and this is called gastrulation. While universally recognized as a developmental step in animal embryos, gastrulation comes in a broad diversity of shapes and flavors, and precisely defining it can be a tricky task. The simplest definition that still captures the essence of the phenomenon is probably the following: gastrulation is what happens when you stop being a ball.

Why should we gastrulate?

Gastrulation is so familiar to us that we easily forget that its very existence is mysterious. Why do cells need to move at all? Why should the making of an animal require elaborate, origami-like folding, complex migrations and relocations? Why can’t embryos directly make the cells in their final needed place? This would certainly be possible: all major independently evolved multicellular groups (plants, fungi, and brown algae) managed to reach high levels of organization only by the use of oriented cell divisions, differential growth, and a little bit of trimming by programmed cell death. No cell migration involved, no massive tissue folding needed. Yet why does the making of all animals, from jellyfish to cockroaches to zebras, require this beautifully absurd, but universal, dance?

The historically first solution to this riddle came from the man who first recognized gastrulation (and who coined the word), the German biologist Ernst Haeckel. While Haeckel’s figure recently attracted a lot of fierce (and maybe excessive) criticisms for the inaccuracies he introduced in his drawings of embryos, he also made many seminal contributions to biology – one of which was to identify, and tentatively explain, the universal occurrence of gastrulation. His hypothesis was rooted in the early idea that embryonic development recapitulates evolution: early animals, the proposal goes, were indeed shaped as balls, even as adults, but they had the possibility to form a transient cavity by folding inwards when they touched the substrate or encountered a piece of food. The simple, temporary gut thus created allowed to locally concentrate digestive enzymes, and maybe also to trap preys. This structure was later stabilized during evolution as a permanent digestive cavity. Our own cells, Haeckel further claimed, still have to move inside during embryonic development because they recapitulate this ancestral response. By analogy to the embryonic stage (gastrula), the hypothetical ancestor was called Gastraea.

The Gastrae hypothesis for early animal evolution. Here, early animals are depicted as flattened balls, that could transiently form a cavity by invagination when they were encountering food. This transient cavity would have then changed into a permanent structure, with cells on the inner and the outer side acquiring different identities (ectoderm and endoderm, respectively). A similar change of shape, with external cells having to move inside, would be recapitulated, in a modified form, during gastrulation in all animal embryos. After http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2007/02/21/basics-gastrulation-invertebra/

Still now, the Gastraea hypothesis has its supporters and its critics. Whether one loves it or hates it, it probably remains the only attempt so far at solving the riddle of gastrulation. Yet one can still wonder: even if the Gastraea hypothesis explains how gastrulation appeared, why has it been universally maintained since then? Why could animal embryos deeply modify gastrulation movements in evolution (one would hardly recognize Haeckel’s Gastraea in a human or a nematode gastrula) but never completely abolish them? Could movements perform a so far unrecognized function, one that would provide a selective pressure to maintain them?

Gastrulation movements provide ancient mechanical signals to determine cell identity

We set to investigate this question in a project carried out in Emmanuel Farge’s lab (Institut Curie, Paris). The activity of the lab has concentrated, over the past 10 years, on demonstrating that morphogenetic movements during embryonic development perform another function besides the establishment of shape: they are also signals. Cells can perceive when the movements of neighboring cells are deforming them, and react by turning on or off the expression of certain developmental genes. Thus, mechanical strains that accompany morphogenetic movements during development are not only an output of the regulatory activity of the genome, but, in turn, provide inputs that feed back on gene expression. However, examples of this phenomenon remained few (mechanical induction of the transcription factor Twist in the anterior midgut of drosophila embryos for example, or mechanical induction of joint fate at the articulation of two bones during early mouse development). Moreover, these examples were all disconnected – each case study on a model organism revealed a completely different picture from previously investigated species, providing little support for any evolutionarily ancient function for mechanotransduction in development.

We set out to test one precise hypothesis: do mechanotransduction pathways respond to gastrulation movements? Are mechanical signals necessary to induce the correct molecular cell identity at the correct position when the animal stops being a ball and first starts acquiring its shape? If the answer were yes, and if this phenomenon were of general importance in animal embryos (with the same transduction pathways responding to deformations and activating the same downstream cassette in the gastrulas of several, distantly related species), this could contribute to explain why gastrulation movements were conserved in evolution: the mechanical cues they provide are a pre-requirement for cell fate specification.

We started by comparing zebrafish and drosophila, that belong to the two main branches of the bilaterian evolutionary tree (Deuterostomia and Protostomia). In both species, we used assays that first blocked gastrulation movements, and then performed exogenous deformations to artificially rescue mechanical strains. Interestingly, in both species, we found that blocking gastrulation movements blocked the expression of certain developmental genes, and that rescuing movements reestablished it. Moreover, both the identity of the responding cells and the identity of the responding genes turned out to be similar in both species: in both cases, the responsive cells were the presumptive mesoderm, and mechanical signals activated key early transcription factors for early mesoderm specification – notail in zebrafish (a brachyury orthologue) and twist in drosophila. Finally, in both species, the mechanotransduction pathway turned out to be the same: cell deformation in the presumptive mesoderm promotes phosphorylation of β–catenin at a conserved site (tyrosine 654 in zebrafish and 667 in drosophila), which in turns promotes its translocation into the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor and turns on mesoderm genes.

Mechanical induction of mesoderm identity in flies

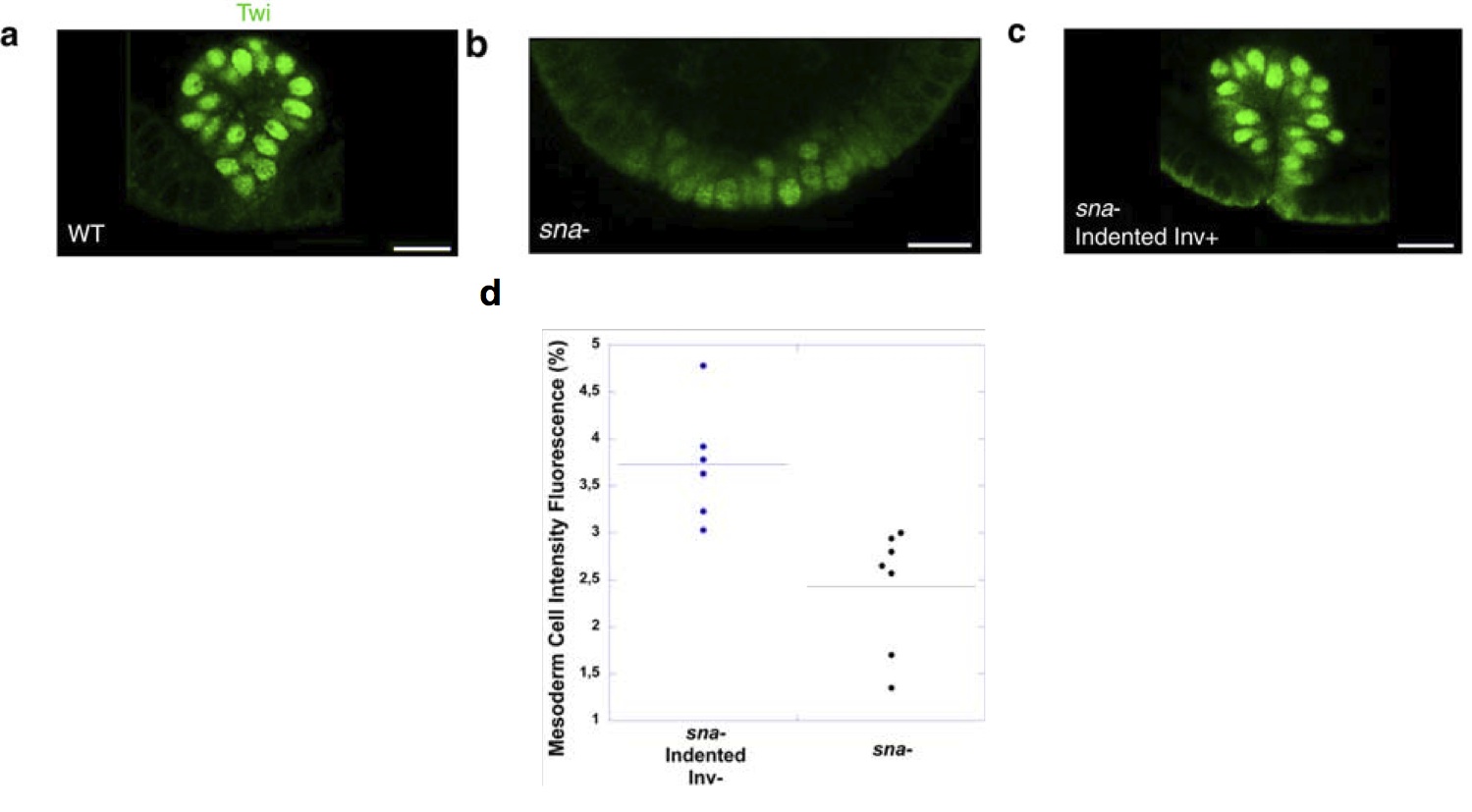

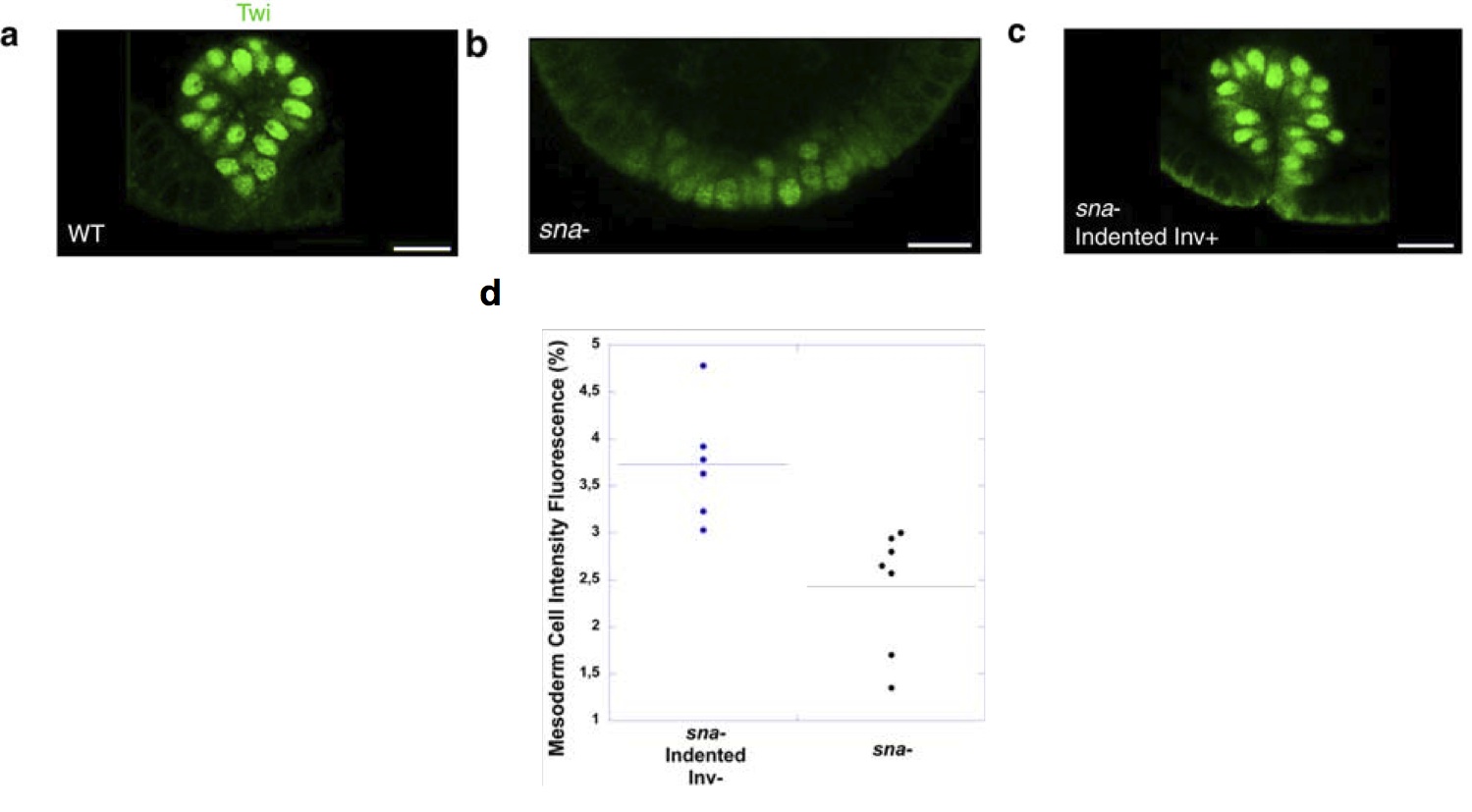

In Drosophila, the study was performed on snail-/- mutants. These mutants lack invagination of the ventral furrow, which gives rise to the bulk of the trunk mesoderm in the fly. Previous research had demonstrated that gently poking the ventral side of a drosophila snail mutant rescues invagination with 70% of success. In snail mutants lacking invagination, twist expression fades prematurely in the mesoderm (though it is correctly initiated at earlier stages). Rescuing invagination rescues a high level of twist expression in the ventral furrow. Strikingly, even in the 30% of cases when poking does not rescue invagination, a small increase of twist expression was observed in response to cell deformation. Altogether, these results indicated that the mechanical constraints linked to ventral furrow invagination maintain a high level of Twist expression in the drosophila mesoderm.

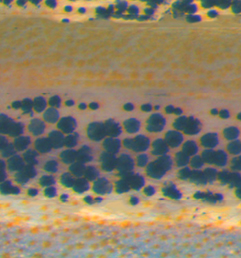

Twist immunostaining in the ventral furrow (future mesoderm) of Drosophila embryos. (a) is a wild-type individual, (b) a sna mutant with reduced Twist expression and (c) a sna mutant where invagination has been rescued by indentation. This also rescues high levels of Twist. (d) levels of Twist measured in sna mutants that were poked, but failed to respond by invaginating; the quantification shows that poking alone partially rescued Twist expression.

Mechanical induction of mesoderm identity in fish

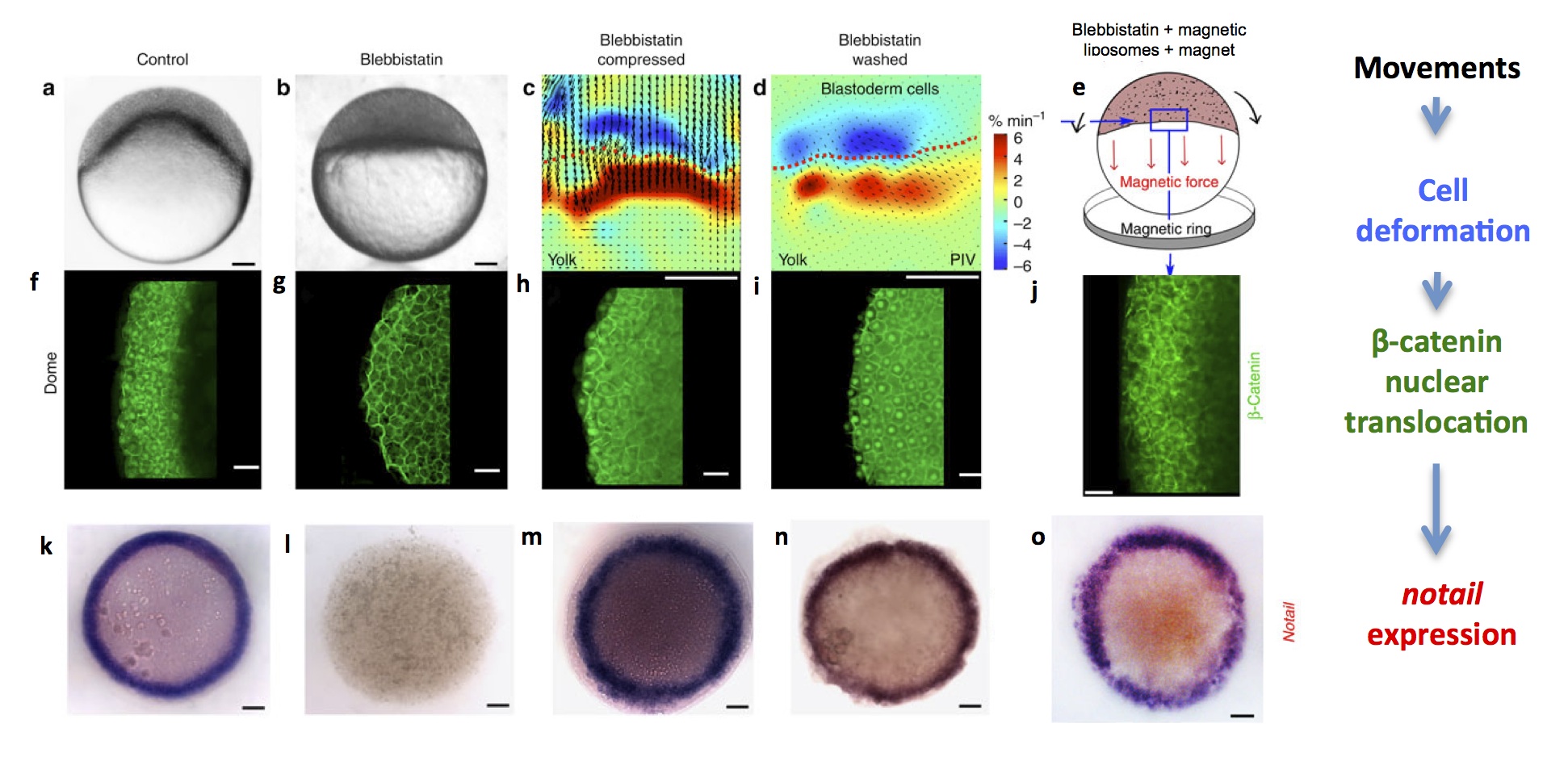

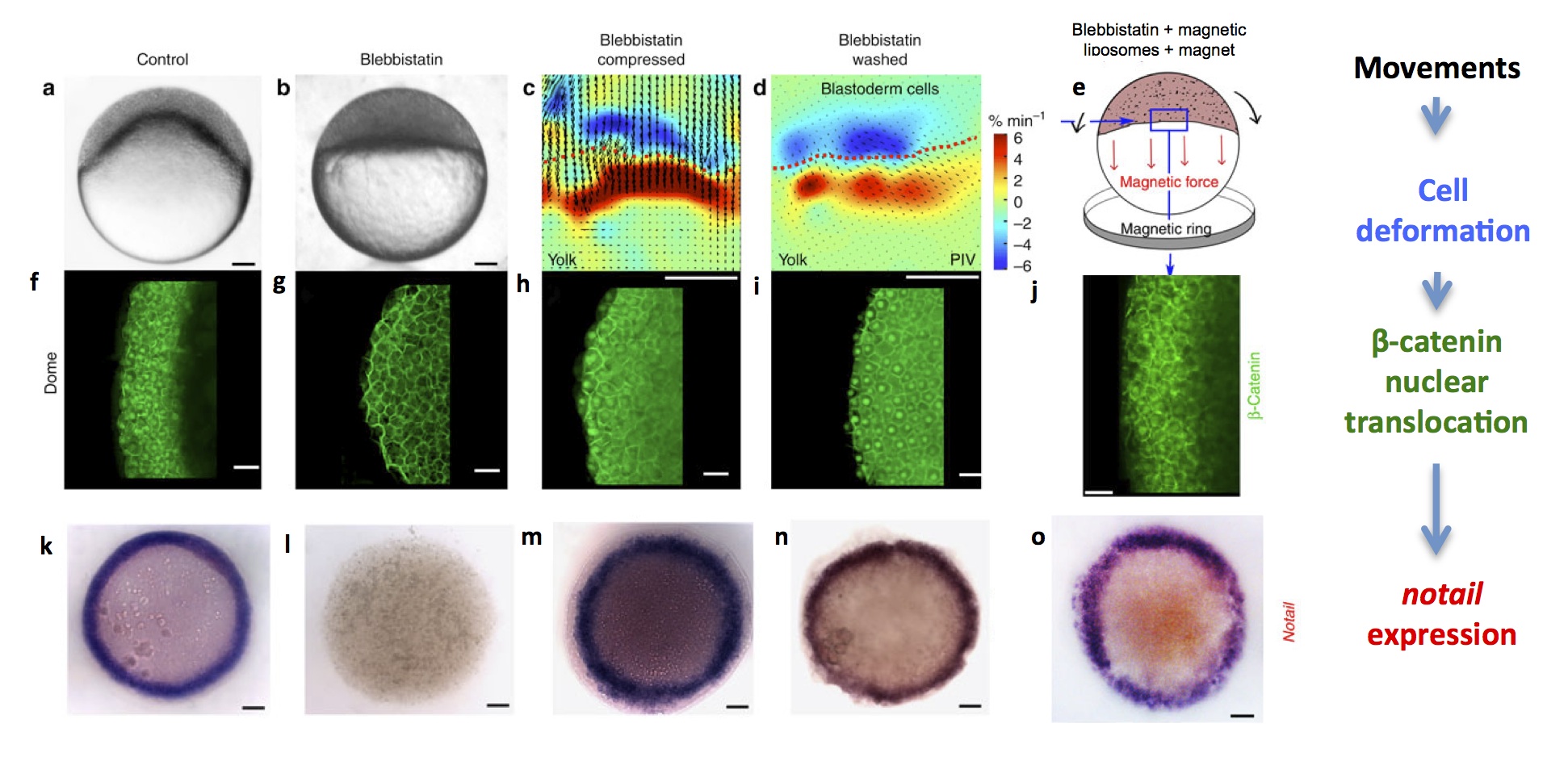

In zebrafish, the first morphogenetic movement that happens is epiboly: cleavage produces a small mass of cells on top of a ball of nutritive yolk. The first task of the cells is to enclose the yolk, and to achieve this, they start spreading over it and engulfing it. At the beginning of this spreading movement, the cells of the presumptive mesoderm – which form a marginal ring around the bottom of the mass of cells – undergo a specific deformation: they are stretched and dilated. Shortly after being deformed, these cells show nuclear translocation of β–catenin and, under the control of β–catenin transcription activity, start expressing notail, thus acquiring the first molecular signs of mesoderm identity. Could cell deformations due to the first gastrulation movements be required to induce this identity, as they are in drosophila? We demonstrated, by blocking gastrulation movements using specific inhibitors of non-muscle myosin II (blebbistatin) or microtubules (nocodazole), that deformation is indeed required for β–catenin to move into the nuclei and for notail expression to be initiated. Moreover, rescuing movements by artificial bulk compression of the embryo, by washing away blebbistatin, or by injecting magnetic particles in the embryos and using a magnetic ring to pull the marginal cells, resulted in a rescue of β–catenin nuclear translocation and notail expression.

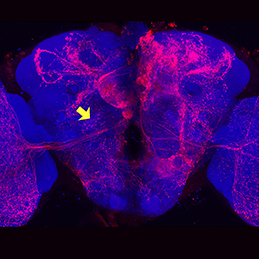

Zebrafish embryos at the dome stage (beginning of gastrulation). (a) controls, (b) embryos with movements blocked by blebbistatin treatment, (c) PIV (Particle Image Velocimetry) quantification of cell deformations at the margin of artificially compressed blebbistatin-treated embryos (blue is dilation and red is compression), (d) PIV quantification of cell deformations after washing blebbistatin, which prompts resumal of wild-type movements and (e) schematic drawing of magnetically deformed embryos. (f-j) β–catenin immunostaining of embryos in each experimental condition, showing that cell movements are necessary and sufficient for nuclear β–catenin translocation in marginal cells. (k-o) brachyury in situ hybridization of embryos in each condition, showing that cell movements are necessary and sufficient for brachyury expression around the margin (future mesoderm).

An ancient function for mechanotransduction in mesoderm induction?

The drosophila/zebrafish comparison suggested one tempting conclusion: that mesodermal identity was under the control of mechanical signals already in the last common bilaterian ancestor, more than 570 million years ago, and that mechanical signals still induce mesoderm identity in the embryos of most, and maybe even all, bilaterian animals. Indeed, one strikingly recurrent theme in bilaterian development is the expression of brachyury along the blastopore – an observation that could be elegantly explained if brachyury were under the control of conserved mechanical strains.

If so, one might need to consider a revised status for embryonic geometry in developmental biology – not only as an output of gene expression, but as an integral part of the regulatory networks that control development. By doing so, we might get insights into how the evolution of embryonic shape and the evolution of differentiated cell identity (often considered as largely independent issues) actually constrain each other. We might also come closer to understanding why, in the individual development of every single animal of our planet, the dance of gastrulation needs to reenact, in an unbroken chain since our Precambrian ancestors, the way the first animals stopped looking like balls, and paved the way for the diversity of animal shapes we see today.

References

Brunet, T., Bouclet, A., Ahmadi, P., Mitrossilis, D., Driquez, B., Brunet, A.-C., Henry, L., Serman, F., Béalle, G., Ménager, C., et al. (2013). Evolutionary conservation of early mesoderm specification by mechanotransduction in Bilateria. Nat. Commun. 4. (open access)

Piccolo, S. (2013). Developmental biology: Mechanics in the embryo. Nature 504, 223–225.

On the Gastraea theory

Wolpert, L. (1992). Gastrulation and the evolution of development. Dev. Camb. Engl. Suppl. 7–13.

On Haeckel’s drawings

the case for the fraud: Richardson, M.K., Hanken, J., Selwood, L., Wright, G.M., Richards, R.J., Pieau, C., and Raynaud, A. (1998). Haeckel, embryos, and evolution. Science 280, 983, 985–986.

the case against the fraud: Richards, R.J. (2009). Haeckel’s embryos: fraud not proven. Biol. Philos. 24, 147–154.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(1 votes)

(1 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) On p.

On p.  The role of Notch signalling in pericyte development is also investigated by Raphael Kopan and colleagues (p.

The role of Notch signalling in pericyte development is also investigated by Raphael Kopan and colleagues (p. Neuronal subtype specification is regulated by the coordinated action of transcription factors. Any one factor may be expressed in multiple subtypes, but specification is achieved based on the precise combination of factors and is therefore context dependent. In this issue (p.

Neuronal subtype specification is regulated by the coordinated action of transcription factors. Any one factor may be expressed in multiple subtypes, but specification is achieved based on the precise combination of factors and is therefore context dependent. In this issue (p.  The striped pattern of the zebrafish skin offers an excellent model system in which to study biological pattern formation. Previous studies have shown that the interactions between melanophores and xanthophores are crucial for pattern formation, but little is known regarding the molecular mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon. Now, on p.

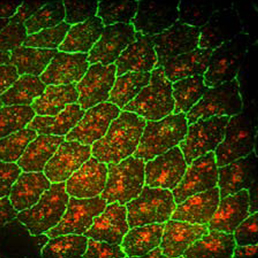

The striped pattern of the zebrafish skin offers an excellent model system in which to study biological pattern formation. Previous studies have shown that the interactions between melanophores and xanthophores are crucial for pattern formation, but little is known regarding the molecular mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon. Now, on p.  Neuronal diversity in Drosophila is generated by the temporal specification of type II neuroblasts (NBs) and their progeny, the intermediate neural progenitors (INPs). Multiple transcription factors are expressed in a birth order-dependent manner within each INP lineage, but whether this temporal patterning gives rise to discrete neuronal sets from each individual INP cell is unclear. Now, on p.

Neuronal diversity in Drosophila is generated by the temporal specification of type II neuroblasts (NBs) and their progeny, the intermediate neural progenitors (INPs). Multiple transcription factors are expressed in a birth order-dependent manner within each INP lineage, but whether this temporal patterning gives rise to discrete neuronal sets from each individual INP cell is unclear. Now, on p.  Dorsal closure is a morphogenic process that involves the interplay of mechanical forces as two opposing epithelial sheets come together and fuse. These forces impact cell shape and the rate of morphogenesis, but the molecular pathways that translate mechanical force into phenotype are not well understood. Now, on p.

Dorsal closure is a morphogenic process that involves the interplay of mechanical forces as two opposing epithelial sheets come together and fuse. These forces impact cell shape and the rate of morphogenesis, but the molecular pathways that translate mechanical force into phenotype are not well understood. Now, on p.  Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are the precursors of sperm and eggs, which generate a new organism that is capable of creating endless new generations through germ cells. Here, Magnúsdóttir and Surani summarise the fundamental principles of PGC specification during early development and discuss how it is now possible to make mouse PGCs from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, and indeed somatic cells if they are first rendered pluripotent in culture. See the Primer on p.

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are the precursors of sperm and eggs, which generate a new organism that is capable of creating endless new generations through germ cells. Here, Magnúsdóttir and Surani summarise the fundamental principles of PGC specification during early development and discuss how it is now possible to make mouse PGCs from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, and indeed somatic cells if they are first rendered pluripotent in culture. See the Primer on p.  In their Development at a Glance article, Centanin and Wittbrodt provide an overview of retinal neurogenesis in vertebrates and discuss implications of the developmental mechanisms involved for regenerative therapy approaches. See the poster article on p.

In their Development at a Glance article, Centanin and Wittbrodt provide an overview of retinal neurogenesis in vertebrates and discuss implications of the developmental mechanisms involved for regenerative therapy approaches. See the poster article on p.  (13 votes)

(13 votes)