Here are the research highlights from the current issue of Development:

Fishing out adult neural stem cells

Adult neural stem cells (NSCs) hold great potential for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and nervous system injuries. To date, adult neurogenesis has been mainly studied in rodents but, on p. 1459, Laure Bally-Cuif and co-workers use GFP-encoding viruses and clonal analyses to characterise NSCs in the adult zebrafish brain. Zebrafish grow throughout life and maintain germinal centres in the brain that continually add new cells to the nervous system. The telencephalic germinal zone contains quiescent radial glial progenitors and actively dividing neuroblasts and the researchers now show that these progenitors have different division modes and fates. Thus, neuroblasts primarily undergo a limited amplification phase followed by symmetric neurogenic divisions, whereas radial glia self-renew and generate different cell types, a result that identifies them as bona fide NSCs. Importantly, the researchers also show that most radial glia divide symmetrically, which amplifies and maintains the NSC pool. These and other results establish zebrafish as an important model system for studying adult neurogenesis.

All change: stepwise in vivo transdifferentiation

Many differentiated cells can be reprogrammed to adopt new identities; reprogramming can occur through an embryonic stem cell-like state or by direct conversion to another cell type (transdifferentiation). The latter route is poorly understood but, here, Sophie Jarriault and colleagues provide detailed analyses of a natural direct reprogramming event – the in vivo transdifferentiation of a C. elegans rectal cell into a motoneuron (see p. 1483). The researchers show that when the rectal cell undergoes transdifferentiation, it adopts a temporary state that lacks the characteristics of both the initial and final cellular identities before undergoing stepwise redifferentiation into a motoneuron. Dedifferentiation, they report, can occur without cell division, and redifferentiation requires the conserved transcription factor UNC-3. Importantly, the intermediate dedifferentiated stage has restricted plasticity. Together, these results suggest that direct in vivo reprogramming in C. elegans (and possibly other species) involves transition through discrete stages and that tight control mechanisms restrict cell potential at each stage, a conclusion with important implications for regenerative medicine.

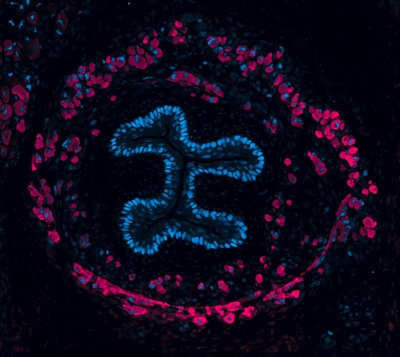

Apoptosis sets the speed of morphogenesis

During development, dynamic cell behaviours are carefully orchestrated to ensure that morphogenesis is completed within the correct developmental time frame, but how is this achieved? Erina Kuranaga and colleagues (p. 1493) have been examining genital morphogenesis in Drosophila and report that apoptosis controls the speed of looping morphogenesis in the fly’s male terminalia. The terminalia is an asymmetric looping organ in which the internal genitalia (spermiduct) loops around the hindgut. During maturation of the internal genitalia, the male terminalia rotates 360° clockwise. Previous work has shown that the adult male terminalia is incorrectly orientated in mutants for apoptotic signalling. Now, using time-lapse imaging, the researchers show that, in normal flies, genitalia rotation accelerates as development proceeds but that this acceleration is impaired when the activity of apoptotic signalling components is reduced. The researchers propose that apoptosis drives the movement of cell sheets during the morphogenesis of male terminalia, thereby ensuring that morphogenesis is completed within a limited developmental time frame.

Xist marks the spot

In XX female mammals, the inactivation of one X chromosome during development equalises the levels of X-linked gene products in females with levels in males. The Xist locus regulates X inactivation by producing Xist, a non-coding RNA that coats and silences the chromosome from which it is transcribed. Now, on p. 1541, Neil Brockdorff and co-workers analyse X inactivation in XistINV mice, which carry a mutation in which a conserved region of Xist exon 1 is inverted. Inheritance of XistINV on the maternal X chromosome in female embryos results in secondary non-random X inactivation, they report, which indicates that the inversion affects Xist-mediated silencing but not Xist gene regulation. Moreover, XistINV inheritance on the paternal X chromosome leads to embryonic lethality because of failed imprinted X inactivation in extra-embryonic tissues. Other analyses show that XistINV RNA localises in cis to the X chromosome but with reduced efficiency. Thus, the researchers conclude, conserved Xist exon 1 sequences are important for Xist RNA localisation and, consequently, X-linked gene silencing.

Muscle building: actin polymerisation drives myoblast fusion

Myoblast fusion, which is essential for skeletal muscle development, involves cell recognition and adhesion, followed by cell membrane breakdown and multinucleate syncitia formation. Here, Susan Abmayr and colleagues clarify the molecular mechanism of myoblast fusion in Drosophila embryos (see p. 1551). In Drosophila, the initial myoblast fusion event occurs asymmetrically between a founder cell (which patterns the musculature) and a fusion-competent myoblast (FCM). The researchers report that the non-conventional guanine nucleotide exchange factor Myoblast city (Mbc) is required in the FCMs but not in the founder cells for myoblast fusion, and that Mbc activates the small GTPase Rac1 in the FCMs. Notably, Mbc, active Rac1 and F-actin foci are concentrated in the FCMs at their site of contact with founder cells, and Mbc is essential for the formation and organisation of F-actin foci and the cytoskeleton in the FCMs. The researchers suggest, therefore, that Mbc-dependent actin polymerisation in FCMs may be one of the driving forces behind Drosophila myoblast fusion.

Arteriovenous malformations go with the flow

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are direct connections between arteries and veins that arise during active angiogenesis. Most AVMs are sporadic but some are associated with mutations in genes involved in TGFβ signalling. For example, mutations in activin receptor-like kinase 1 (ALK1, a TGFβ receptor) are implicated in the vascular disorder hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia 2 (HHT2). But what are the molecular and cellular errors that lead to AVM formation? On p. 1573 Beth Roman and colleagues address this question by analysing AVM development in alk1 mutant zebrafish embryos. They report that blood flow triggers alk1 expression in nascent arteries exposed to high haemodynamic forces and that Alk1 normally limits vessel calibre. In alk1 mutants, however, Alk1-dependent arteries are enlarged, and the downstream vessels adapt to the consequent increases in blood flow by retaining normally transient arteriovenous drainage connections, which subsequently enlarge to form AVMs. This two-step model for AVM formation suggests that HHT2 treatments might focus on preventing arterial enlargement and/or abrogating flow-induced AVM development.

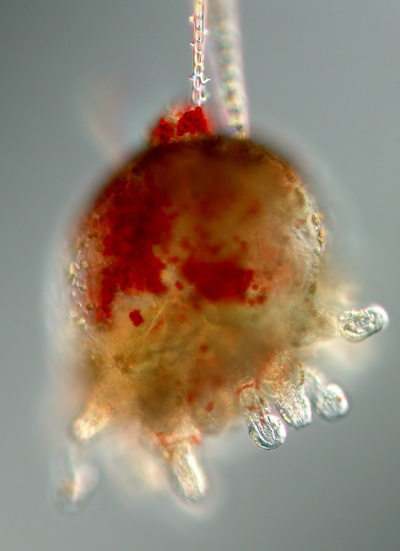

Plus…

As part of the Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology series, Technau and Steele introduce Cnidaria and discuss how studies of this diverse phylum, which includes corals, sea anemones, jellyfish and hydroids, have informed our understanding of bilaterian evolution and development.

See the Primer article on p. 1447

Also have a look at the other articles in the Featured Topic on Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Loading...

Loading...

Tags: ALK1, apoptosis, arteriovenous malformations, morphogenesis, myoblast fusion, neural stem cells, neuroblasts, terminalia, transdifferentiation, UNC-3, Xist

Categories: Research

![]() You’ve seen the news: ES cells generate a 3D retinal structure. But what does this tell us about eye development?

You’ve seen the news: ES cells generate a 3D retinal structure. But what does this tell us about eye development?

(6 votes)

(6 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(5 votes)

(5 votes)