PhD in Fetal Alcohol Syndrome starting September 2016 in University College Dublin, Ireland.

Posted by Deirdre Brennan, on 22 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Posted by Deirdre Brennan, on 22 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Posted by the Node, on 22 February 2016

Here is some developmental biology related content from other journals published by The Company of Biologists.

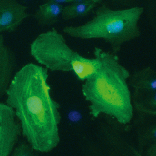

Using the developmental biology toolkit to study cancer

review the similarities between embryogenesis and cancer progression and discuss how the concepts and techniques of developmental biology are being applied to provide insight into all aspects of tumorigenesis. Read the review here [OPEN ACCESS].

review the similarities between embryogenesis and cancer progression and discuss how the concepts and techniques of developmental biology are being applied to provide insight into all aspects of tumorigenesis. Read the review here [OPEN ACCESS].

A new gestational diabetes mellitus model

He and colleagues successfully establish a new chick embryo model to study the molecular mechanism of hyperglycemia-induced eye malformation. Read the paper here [OPEN ACCESS].

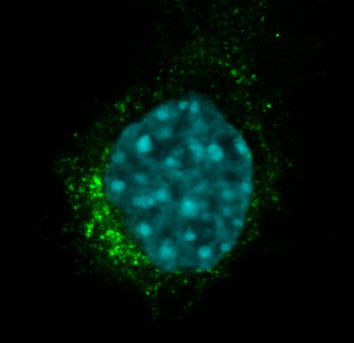

Cathepsin D sorting in neurons

Jadot and colleagues show that SEZ6L2 can serve as a receptor to mediate the sorting of cathepsin D to endosomes, and that this sorting process might contribute to neuronal development. Read the paper here.

Demethylase activity in ESC differentiation

Becker and colleagues show that KDM6-specific H3K27me3 demethylase activity is crucially involved in the DNA damage response and survival of differentiating murine ESCs. Read the paper here.

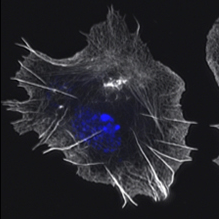

Hic-5 in angiogenesis and myofibroblast differentiation

Two studies investigate the role of focal adhesion protein Hic-5. Bayless and colleagues examine whether Hic-5 regulates endothelial sprouting in three dimensions (here), while Van De Water and co-workers report a crucial role for this protein in myofibroblast differentiation in response to TGF-β (here).

A role for miR-20a in endothelial-mesenchymal transition

Krenning and colleagues show that FGF2 induces the expression of miR-20a, a non-coding microRNA identified in a previous screen, which targets the TGFβ receptor complex and abolishes endothelial–mesenchymal transition. Read the paper here.

Krenning and colleagues show that FGF2 induces the expression of miR-20a, a non-coding microRNA identified in a previous screen, which targets the TGFβ receptor complex and abolishes endothelial–mesenchymal transition. Read the paper here.

Characterising the fourth WASP

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome proteins (WASPs) are nucleation-promoting factors that differentially control the Arp2/3 complex. Here, Bogdan and colleagues characterized WHAMY, the fourth Drosophila WASP family member, and show that it plays a role in myoblast fusion, macrophage cell motility and sensory organ development in Drosophila. Read the paper here.

Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome proteins (WASPs) are nucleation-promoting factors that differentially control the Arp2/3 complex. Here, Bogdan and colleagues characterized WHAMY, the fourth Drosophila WASP family member, and show that it plays a role in myoblast fusion, macrophage cell motility and sensory organ development in Drosophila. Read the paper here.

Loss of PPARγ leads to impaired angiogenesis

Loss of PPARγ in mice leads to osteopetrosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension in mice, and is associated with vascular disease. Alastalo and colleagues now report a novel mechanism by which PPARγ can regulate endothelial cell homeostasis and angiogenesis. Read the paper here.

The embryos of Austrofundulus limnaeus, a killifish that resides in ephemeral ponds, routinely enter diapause II, a reversible developmental arrest promoted by endogenous cues rather than environmental stress. Toni and Padilla use A. limnaeus to examine epigenetic features associated with embryonic arrest. Read the paper here.

The embryos of Austrofundulus limnaeus, a killifish that resides in ephemeral ponds, routinely enter diapause II, a reversible developmental arrest promoted by endogenous cues rather than environmental stress. Toni and Padilla use A. limnaeus to examine epigenetic features associated with embryonic arrest. Read the paper here.

Posted by stemcellsjobs, on 22 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Department/Location: Wellcome Trust – Medical Research Council Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, University of Cambridge

Salary: £28,982-£29,847

Reference: PS08402

Closing date: 20 March 2016

Fixed-term: The funds for this post are available for 2 years in the first instance.

The Wellcome Trust – Medical Research Council Stem Cell Institute at the University of Cambridge provides outstanding scientists with the opportunity and resources to undertake ground-breaking research into the fundamental properties of mammalian stem cells (http://www.stemcells.cam.ac.uk/).

Transcriptional control of lineage decisions in embryonic stem cells.

Applications are invited for a postdoctoral position to investigate the molecular control of embryonic stem cell lineage commitment and differentiation. The successful applicant will be part of an interdisciplinary collaboration between The Cambridge Stem Cell Institute and Microsoft Research to understand how information is processed by individual stem cells to bring about cell fate decisions.

For this position demonstrated experience in the analysis of transcriptional mechanisms will be required. The candidate is expected to have considerable expertise in molecular biological and biochemical techniques, basic mammalian cell culture, and to be familiar with basic programming and computational methods. Previous experience in higher-level programming, mammalian stem cell biology, and/or chromatin biochemistry is highly desired. The position will be based in the Hendrich laboratory and is available immediately.

You should have been awarded a PhD degree or equivalent and have several years laboratory experience.

To apply online for this vacancy and to view further information about the role, please visit: http://www.jobs.cam.ac.uk/job/9561. This will take you to the role on the University’s Job Opportunities pages. There you will need to click on the ‘Apply online’ button and register an account with the University’s Web Recruitment System (if you have not already) and log in before completing the online application form.

The closing date for all applications is the Sunday 20 March 2016.

Please upload your Curriculum Vitae (CV) and a covering letter in the Upload section of the online application to supplement your application. If you upload any additional documents which have not been requested, we will not be able to consider these as part of your application.

Informal enquiries are also welcome via email to: Dr Brian Hendrich Brian.Hendrich@cscr.cam.ac.uk, Dr Sara-Jane Dunn Sara-Jane.Dunn@microsoft.com or to jobs@stemcells.cam.ac.uk.

Interviews will be held on Monday 04 April 2016. If you have not been invited for interview by 01 April 2016, you have not been successful on this occasion.

Please quote reference PS08402 on your application and in any correspondence about this vacancy.

The University values diversity and is committed to equality of opportunity.

The University has a responsibility to ensure that all employees are eligible to live and work in the UK.

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 18 February 2016

Cat Vicente, who many of you will know as the Node’s Community Manager, is moving on to exciting new ventures. We’re really sorry to see her go – I’m sure you’ll agree that Cat has done a fantastic job running the Node over the past few years and she’ll be sorely missed, but we wish her all the best for the future.

And this means that her job is up for grabs – would you like to be the next Community Manager of the Node?

You can find full details of the position here, including more information on what the job actually entails, what kind of person we’re looking for, and the timeline for application.

Informal queries can be directed to our HR department, or feel free to drop me an email if you want to know more.

Posted by Katherine Brown, on 18 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

The Company of Biologists and its journal Development are seeking to appoint a new Community Manager to run its successful community website the Node and the journal’s social media activities.

Launched in 2010, the Node is the place for the developmental biology community to share news, discuss issues relevant to the field and read about the latest research and events. We are now looking for an enthusiastic and motivated person to develop and maintain the site.

Core responsibilities of the position include:

Applicants should have research experience in a relevant scientific field, ideally a PhD in developmental or stem cell biology. The successful candidate will have proven blogging and social media skills (ideally including experience with WordPress) and a clear understanding of the online environment as it applies to scientists. Applicants should have excellent writing and communication skills, and strong interpersonal and networking abilities – both online and in person. Experience with additional media, such as video or podcasting, would be an advantage. We are looking for an individual with fresh ideas, a willingness to learn new skills and to contribute broadly to the Company’s activities.

This is an exciting opportunity to develop an already successful and well-known site, engaging with the academic, publishing and online communities. The Community Manager will work alongside an experienced in-house team, including Development’s Executive Editor, as well as with the journal’s international team of academic editors. Additional responsibilities may be provided for the right candidate. The position is based in the Company of Biologists’ attractive modern offices on the outskirts of Cambridge, UK.

The Company of Biologists exists to support biologists and inspire advances in biology. At the heart of what we do are our five specialist journals – Development, Journal of Cell Science, Journal of Experimental Biology, Disease Models & Mechanisms and Biology Open – two of them fully open access. All are edited by expert researchers in the field, and all articles are subjected to rigorous peer review. We take great pride in the experience of our editorial team and the quality of the work we publish. We believe that the profits from publishing the hard work of biologists should support scientific discovery and help develop future scientists. Our grants help support societies, meetings and individuals. Our workshops and meetings give the opportunity to network and collaborate.

Applicants should send a CV along with a covering letter that summarises their relevant experience (including, if possible, links to online activities and/or samples of science writing), salary expectations, and why they are enthusiastic about this opportunity.

Applications and informal queries should be sent by email no later than March 14th to our HR department.

We anticipate conducting interviews in the week commencing April 4th, and may request written tests in advance of any interview.

Applicants should be eligible to work in the UK.

Posted by Benjamin Prud'homme, on 18 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

Evolution of the gene regulatory network controlling wing pigmentation patterns in Drosophila

We are looking for a PhD student to study the evolution of the gene regulatory network controlling the formation of a wing pigmentation pattern in Drosophila species. This wing spot has emerged from a spot-less ancestor, around 15 millions years ago, and then diversified in shape, color and intensity between species.

The goal of the project is to peer into the genomic changes responsible for these different evolutionary transitions. The student will use comparative functional genomics across species to identify candidate genes and cis-regulatory sequences associated with these transitions. These candidates will be further validated in vivo by functional manipulations using genome editing approaches.

Ultimately, these results will help to better understand how a gene regulatory network emerge during evolution and give rise to a novel morphological trait, and how alterations of this network underlie morphological diversification of a morphological trait.

Candidates (from any nationality, with no requirement to understand French) are expected to have a background in developmental biology, genetics, and a strong interest in evolution.

Please send a CV, a motivation letter, a description of research experience and interests and e-mail contact for 2-3 references to benjamin.prudhomme@univ-amu.fr

The position is funded for 3 years by an ERC grant and must start before July 1st 2016.

Our lab is part of the Institute of Developmental Biology of Marseille (IBDM), an interdisciplinary research center studying developmental biology and neurobiology. More information about the lab and the institute can be found here: www.prudhommelab.com & www.ibdm.univ-mrs.fr

Posted by Daniel_Leite, on 17 February 2016

We (Anna Schönauer, Daniel Leite and Christian Bonatto) are PhD students in Alistair McGregor’s group (http://mcgregor-evo-devo-lab.net) at Oxford Brookes University, and it is a pleasure to briefly present our research on spiders. The university is located up on Headington Hill, from where we can look out across the beautiful spires of the great academic city of Oxford. Our research focuses on animal development and evolution using the common house spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum (previously known as Achaearanea tepidariorum). Currently, the topics we are interested in include the regulation of segmentation of the opisthosoma (the posterior region of the spider body) and the evolution and function of microRNAs. Parasteatoda is now emerging as an excellent model to study these biological mechanisms and evolutionary processes.

The Parasteatoda Culture

Our spider culture was originally founded from individuals collected from a basement in Göttingen, Germany. We keep the bulk of our culture in a 25°C room with a multitude of other arthropods and even the departments pet corn snake (Figure 1). To maximise their health and productivity, we feed the spiders twice a week, on Monday and Friday, and the mated female spiders get an extra feed on Wednesday. Depending on their size, both the mated and unmated adult females are fed with crickets, while males and juvenile spiders are given flies.

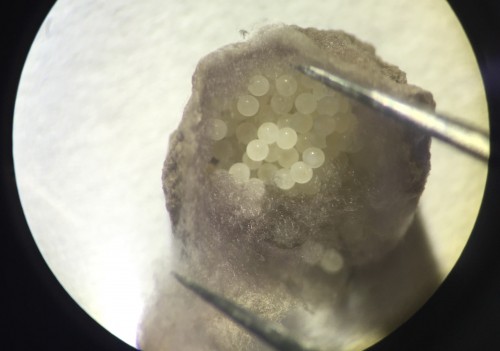

Handling the spiders is safe and easy because they don’t bite humans and in any case their chelicerae can’t penetrate our skin. Adults are small in size (~2 cm leg span) so they can be kept individually in small vials (otherwise they tend to eat each other!). While the females are fairly sedentary, the males are more active as they search for females or subsequently try to escape from them. Once males and females (Figure 2) have reached their final moults they are brought together to mate (Video). From then on we generally keep the male in the same vial as the female, to ensure successful mating but also for the females to have a little snack if she runs out of crickets! We always maintain around 50 mated females to provide enough embryos for experiments and ensure enough cocoons are available to sustain the culture.

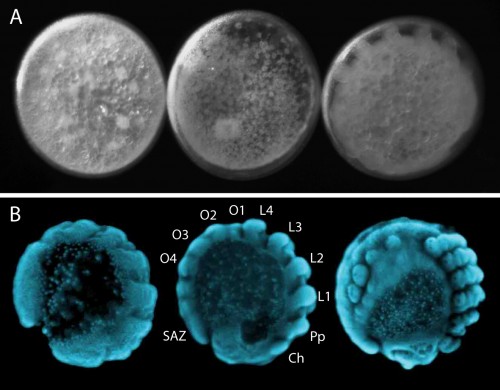

Our regular day starts with collecting cocoons from females, which they produce approximately every four days. There are usually hundreds of embryos per cocoon, all at similar developmental stages (Figure 3). Developing embryos can be kept in halocarbon oil, which makes the otherwise opaque chorion transparent and allows us to observe the developmental stages (Figure 4A). This helps us identify the exact stage of embryogenesis, which is key for the different approaches that we use to study their development. It takes approximately 10 days for the embryos to develop into translucent, hairless, immotile hatchling spiders (Figure 5). Once the juveniles have progressed through several molts and eaten some flies (as well as a few of their brothers and sisters), they are separated into individual vials. In total, after hatching, it takes about another month for Parasteatoda to reach reproductive maturity.

EvoDevo in the spider

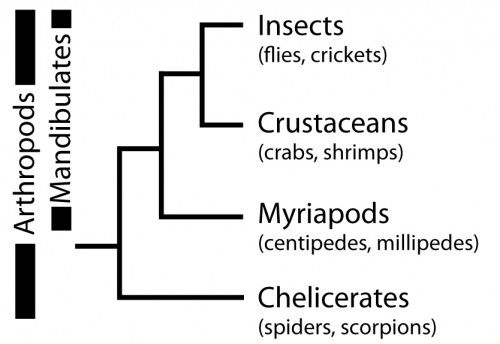

So, why are we using Parasteatoda to ask both developmental and evolutionary questions? Spiders, along with scorpions, mites, ticks and others, belong to the Chelicerata subphylum, which branches at the base of the Arthropoda (Figure 6). Arthropods are a hugely successful and diverse group of animals, however, many evolutionary and developmental studies have focused on insects such as Drosophila (flies), Tribolium (beetles) and Apis (bees). Therefore, investigating chelicerates species like Parasteatoda offers an important perspective to arthropod evolution and development, and to metazoans more broadly.

With the establishment of experimental tools, mainly thanks to pioneering work by Hiroki Oda and Yasuko Akiyama-Oda, Parasteatoda has become a powerful model chelicerate species for EvoDevo research. We can study gene expression in the developing spider with in situ hybridisation (ISH) and can knockdown expression with both parental and embryonic RNA interference (RNAi). A detailed description of embryonic development helps those who work with this spider to make standardised comparisons of developmental time points to interpret expression patterns and RNAi phenotypes.

In addition to the tools used to study gene expression and function during development in Parasteatoda, genomic resources have been developed, including a comprehensive embryonic transcriptome and genome (through the i5k initiative (http://www.arthropodgenomes.org/wiki/i5K). These are indispensable resources for quickly designing probes and RNAi constructs for our research on segmentation, and for mapping RNA sequence data for microRNA discovery.

Segmentation in Parasteatoda

The segmented body plan of arthropods is an important feature that has likely contributed to their evolutionary success and morphological diversity. However, despite conservation of segmentation genes, different mechanisms of segmentation are used among arthropods. In contrast to the somewhat simultaneous development of all segments in Drosophila, Parasteatoda employs a short germ mode of development, which means that some anterior segments are specified first and subsequently the posterior segments are sequentially added from the growth zone or segment addition zone (SAZ) (Figure 4B). In the spider, aspects of vertebrate somitogenesis (Delta/Notch, Wnt signaling), as well as components of the well-studied Drosophila segmentation gene cascade have been found to play a crucial role in posterior segmentation.

In order to functionally test interactions between those components in Parasteatoda, we utilise embryonic RNAi, where dsRNA is injected into a single blastomeres using a protocol developed in the Oda lab. For the injections, embryos have to be lined up one by one on double-sided sticky tape, which can be fairly fiddly and tricky. We use a fluorescent dye in the injection mix so that we can mark the clone of cells that is affected by the RNAi knockdown. After injections we have a peek down the microscope to see where the population of affected cells is located within the developing embryo, but we can also visualize the clone in fixed tissue by staining for Biotin.

In spiders, RNAi knockdown embryos can also be generated by injecting adult females with dsRNA, whereby the knockdown effect is transmitted to their offspring. The injection requires careful positioning of the needle to avoid damaging the heart or other vital organs. One injected female will produce a series of cocoons, with each cocoon exhibiting a different phenotypic severity. The fact that each cocoon consists of many embryos, all at roughly similar stages of development, is really useful for trying to capture this dynamic process of segment addition. When we knock down genes with parental or embryonic RNAi, the results show a disruption of the gene expression in the posterior and the truncation of embryonic tissue and help to decipher the role of particular genes during posterior development.

MicroRNAs in Parasteatoda

MicroRNAs have been shown to be important fine tuners of gene expression and are involved in many developmental process. Much of what we understand about them within invertebrates comes from studies in insects. These studies have found interesting patterns of microRNA evolution within particular lineages such as Drosophila. However, there is a lack of a broader understanding of microRNA evolution and function in development across arthropod species.

To date, the characterisation of microRNA repertoires in chelicerates has been limited to just mites and ticks. Our ongoing research aims to characterise the microRNAs present in Parasteatoda to provide new comparative insights into the evolution of these genes among chelicerate orders and other metazoans. This will allow us to then identify their functions and further investigate their involvement in the evolution of morphological diversity.

The rest of the Lab

Parasteatoda is not the only model organism being studied in the McGregor lab. Our colleagues are investigating the genetic and developmental bases of differences in morphology within and between Drosophila species. This includes studying the evolution and development of compound eyes, which vary in the number and size of ommatidia, and differ in the distribution of rhodopsin proteins. Members of our group also investigate the rapid evolution of male Drosophila genitalia, which always kindles some interesting conversations.

Our lab is very international and it is excellent to have a mixture of people and projects running so that we can learn about experimental approaches and biological processes in different organisms. While spiders and flies may not get along, the humans in the lab often end the evening altogether in one of the amazing pubs in Oxford, over a refreshing pint! If you want to know more about our projects, feel free to visit our website (http://mcgregor-evo-devo-lab.net) and if you have any questions, please email us!

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on a day in the life of developmental biology labs working on different model organisms. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

Posted by the Node, on 16 February 2016

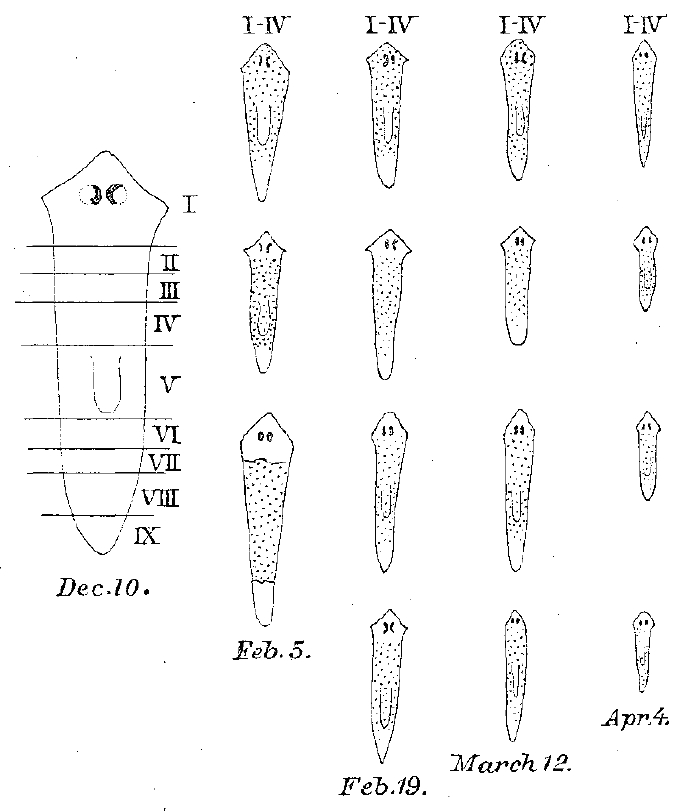

Morgan, T.H. (1898) Experimental studies of the regeneration of Planaria maculata. Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen 7, 364-397

Recommended by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado (Stowers Institute)

Some classic papers are only cited a few times, and the work therein has been largely forgotten. But that does not mean these works are not worth revisiting. Maybe the paper will have a new impact if interpreted in the context of current science. Maybe it provides insights into the mind of the researcher who wrote it- or the early days of now flourishing fields. This 1898 paper by T.H. Morgan, recommended by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, is a great example. Given the author’s name, one could have assumed that it was about Drosophila genetics, but it actually concerns planarian regeneration. As Alejandro tells us “Before fruitflies, genetic maps and a Nobel prize, T. H. Morgan spent a significant amount of his budding career studying the problem of regeneration, and favoured as a model the freshwater planarian. For too long were these formative and influential years forgotten or glossed over by most of Morgan’s biographers. Morgan published at least 11 papers on planarian regeneration, and a book on the topic of regeneration (1901).”

The amazing regenerative abilities of flatworms have been the subject of scientific interest since the end of the 18th century, but much of the observational work done in the early days of the field was forgotten. That is, until more recent times. In the last few decades several planarian regeneration labs have been established and are using modern molecular tools to examine this topic. This 1898 paper is a great example of the observational studies done at the time by scientists interested in regeneration. It is a new field, and no molecular tools are available, so where do you start? At the beginning, of course, which in this case means cutting a lot of planarians and seeing what happens. The paper is written in a wonderfully logical way, and one can follow step by step the thinking process of Morgan. He starts by dividing planarians into several cross sections and examining their regenerative potential. The results observed lead him to address several questions: Is there a limit for how small a fragment can be and still regenerate? Does the shape of the cut play a role? Is remodelling of the old tissues important to ensure that the relative proportions of the regenerated worm are maintained? And are regeneration rates different at the posterior and anterior ends? Morgan does not loose sight of the wider implications of the work and its parallels with normal development. As he states at the end of the paper “The way in which the old tissue transforms itself into a new worm […] show[s] that the material of the body is almost as plastic as that of an undivided or dividing egg”.

Budding regeneration biologists will enjoy following Morgan’s experiments and applying a modern understanding of regeneration to his observations. However, reading this paper will be a delightful exercise even for those outside this field. Modern publishing constraints did not apply in those days, so the work is written almost as a letter to a colleague. It provides a surprisingly candid view of how the experiments were conducted. At one point Morgan writes “About this time I left Woods Holl and carried with me the regenerating pieces, but many of them died as a result, no doubt, of the poor conditions under which they were kept”. This feeling of proximity with the writer and the experiments is accentuated by the figures, which were hand-drawn by Morgan himself. The writing style provides a unique look at the scientist, and this is indeed the reason why Alejandro suggested this paper “I like this particular paper, because it allows us to experience the thought process and experimental reasoning of a brilliant young mind thinking deeply about a complex problem, unaware than in just a few years he would be considered by many the father of modern genetics. The manuscript is an exemplar of clear thinking, elegant and intelligent experimental design”.

Further thoughts from the field

Modern science at times feels too formalized. This paper’s conversational style takes you back to an era of playful, curiosity-driven experimentation and observation. The work was important in cleanly describing important foundational properties of planarian regeneration that we are still struggling to explain to this day.

Peter Reddien, MIT (USA)

As a young graduate student working on Drosophila germ cell development, I became interested in planarian regeneration and started working my way through the classic literature on this topic. Finding Morgan’s early work on planarians was eye opening because it showed how this brilliant scientist approached this problem with the limited tools available to him. Many fundamental discoveries are reported in this paper. For example, he showed that the region in front of the photoreceptors and the pharynx are incapable of regenerating a complete organism. We now know that these regions lack the stem cells that drive planarian regeneration. He also described the amazing remodeling of tissues that restores proper form and proportion to amputated fragments.

Given that we still do not have a satisfactory mechanistic explanation for how these fragments “know” what shape they are supposed to be, it is easy to understand how Morgan made the decision to abandon his work on regeneration in order to study a question that would be more tractable with the tools available to him. In fact, he told a young N. J. Berriill, after hearing that Berrill was working on regeneration in marine worms and ascidian development: “You are being very foolish. I am doing that sort of thing now, as I did when I was very much younger. I can afford to do so now because I am established as the father of genetics in this country and can do what I like. At your age you cannot waste your time. We will never understand the phenomena of development and regeneration.” (Can J. Zool. 61: 947-951, 1983).

Phil Newmark, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (USA)

Springer has kindly provided free access to this paper until the 31st of March 2016!

—————————————–

by Cat Vicente

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

This post is part of a series on forgotten classics of developmental biology. You can read the introduction to the series here and read other posts in this series here.

Posted by Seema Grewal, on 16 February 2016

Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

Endocannabinoids (ECs) are signalling molecules that regulate appetite, mood and pain, and they are studied mostly for their effects on the nervous system. Now, on p. 609, Wolfram Goessling and colleagues uncover a role for EC signalling during liver development and function in zebrafish. Using a chemical screen to identify novel regulators of liver development, the researchers reveal that EC agonists cause an increase in liver size. In line with this, they show that the EC receptors Cnr1 and Cnr2 are expressed in the liver and hepatic region of developing embryos. The TALEN-mediated knockout of these receptors disrupts the differentiation and proliferation, but not the specification, of hepatocytes, giving rise to livers that exhibit architectural and metabolic defects. These defects have a negative long-term impact, causing susceptibility to metabolic insult and disruptions to global lipid metabolism in adult fish. Finally, the authors reveal that the effects of EC signalling are mediated by methionine and by sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factors (Srebfs); methionine supplementation or the overexpression of Srebfs can rescue the liver defects of Cnr mutants. Together, these findings define exciting and novel links between EC signalling, methionine metabolism and liver development.

The Six family transcription factors Six1 and Six2 play non-overlapping roles during kidney development in mice: Six1 controls the initial formation of nephron progenitors, which give rise to nephrons (the functional units of the kidney), whereas Six2 controls progenitor self-renewal. How these factors function during kidney development in humans, however, is less clear. Now, Lori O’Brien, Anton Valouev, Andrew McMahon and co-workers reveal that mouse and human nephron progenitors are differentially regulated by Six family factors (p. 595). Using ChIP-seq analyses, they show that, although mouse Six2 and human SIX2 share many common targets, the SIX1 gene is a unique SIX2 target in humans. In line with this, they demonstrate that Six1 expression is transient and independent of Six2 in the mouse embryonic kidney, whereas SIX1 expression persists in human fetal nephron progenitors and is regulated by SIX2. The researchers also show that SIX1 and SIX2 exhibit overlapping activities in human fetal nephron progenitors, binding to similar sets of targets and showing evidence of cross-regulatory activity. These findings highlight a divergence in Six family function that may underlie species-specific differences in kidney development, such as the extended period of nephrogenesis seen in humans.

Tumour suppressors and proto-oncogenes play fundamental roles in controlling tissue size, shape and organization. It is generally thought that their deleterious effects on tissue development and homeostasis are associated with defects in cell division, but now (p. 623) Yohanns Bellaïche and colleagues reveal mechanical roles for these genes in Drosophila epithelia. They use time-lapse imaging to follow cell behaviour and dynamics in clones of cells that are mutant for the tumour suppressor Fat (Ft). This analysis reveals that Ft mutant clones round up and reduce their cell-cell contacts with surrounding wild-type tissue in the absence of concomitant cell division and over-proliferation. The authors further show that the loss of Ft activity leads to increased levels of the myosin Dachs within clones and the accumulation of Dachs at clone boundaries. Using laser ablation approaches to probe junctional tension, the authors reveal that this polarized distribution of Dachs at clone boundaries increases junctional tension, whereas Dachs accumulation within the clone body decreases tension; these two activities cooperate to promote clone rounding. These findings, together with the analyses of other proto-oncogenes such as Yorkie, Myc and Ras, point to a novel and key function of tumour suppressors and proto-oncogenes.

During cell division, orientation of the mitotic spindle can influence cell fate by controlling the segregation of cell fate determinants. Here, by inactivating the spindle orientation complex protein LGN, Michel Cayouette and co-workers investigate how spindle orientation influences cell fate in two contexts: the mouse retina and the mouse neocortex (p. 575). Their analysis of Lgn-knockout mice reveals that LGN inactivation causes a decrease in the number of vertical divisions (i.e. those occurring with the spindle perpendicular to the neuroepithelium) carried out by retinal progenitor cells (RPCs). By contrast, when looking at the neocortex, they report that LGN increases the incidence of vertical divisions in cortical progenitors. The researchers further show that LGN and hence vertical spindle division in the retina is required for the terminal asymmetric division of RPCs, whereas LGN in the neocortex acts to maintain planar divisions and the self-renewal of cortical progenitors. In summary, these findings demonstrate that LGN inactivation disrupts spindle orientation in both contexts but leads to very different outcomes with regards to cell fate.

The Notch IX meeting, which was held in Athens, Greece in October 2015, brought together scientists working on different model systems and studying Notch signaling in various contexts. Here, we provide a summary of the key points that were presented at the meeting. Although we focus on the molecular mechanisms that determine Notch signaling and its role in development, we also cover talks describing roles for Notch in adulthood. See the Meeting Review on p. 547

The Notch IX meeting, which was held in Athens, Greece in October 2015, brought together scientists working on different model systems and studying Notch signaling in various contexts. Here, we provide a summary of the key points that were presented at the meeting. Although we focus on the molecular mechanisms that determine Notch signaling and its role in development, we also cover talks describing roles for Notch in adulthood. See the Meeting Review on p. 547

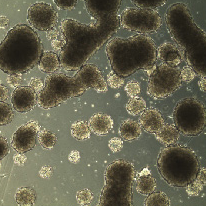

The stomach, an organ derived from foregut endoderm, secretes acid and enzymes and plays a key role in digestion. In their Review, and highlight the molecular mechanisms of stomach development and discuss recent findings regarding stomach stem cells and organoid cultures, and their roles in investigating disease mechanisms. See the Review on p.554

The stomach, an organ derived from foregut endoderm, secretes acid and enzymes and plays a key role in digestion. In their Review, and highlight the molecular mechanisms of stomach development and discuss recent findings regarding stomach stem cells and organoid cultures, and their roles in investigating disease mechanisms. See the Review on p.554

Posted by m.akam, on 16 February 2016

Closing Date: 15 March 2021

The Charles Darwin Professorship of Animal Embryology is endowed by the Bles Fund, which states rather splendidly that it is for “ the promotion and furtherance of biology as a pure science”. Notwithstanding this, holders of this prestigious chair have done work of fundamental significance in embryology and developmental biology, that has subsequently found widespread application. The most recent holder of the chair was Professor Ron Laskey.

The prime criterion for selection will be “an outstanding research record of international stature in some aspect of animal embryology. The chair may be held in any Department or Institute of the School of Biology in Cambridge.

The advertisement is online on the Cambridge University website http://www.jobs.cam.ac.uk/job/9519/, and will shortly appear in Nature and Science. The link for the further particulars is http://www.admin.cam.ac.uk/offices/academic/secretary/professorships/index.html.

The deadline for applications is March 17th.