The International course on Developmental Biology was a great experience, both instructive and mind-opening. All the students were shuttled to the remote and very small fishing village of Quintay, where the CIMARQ, the investigation centre where the course took place, is located. Originally a whaling station, this centre is dedicated to the instruction of professionals in the area of marine resources and has various branches of research mainly based in repopulation strategies of different species ranging from Sea Urchins to the delicious Conger eel or Sole fish. Their main objective is to provide small scale fish-farming to the general community. In fact, on the day of our arrival, after a Lecture on the history of and the main, original questions in Development by Dr. Roberto Mayor, we were given a short practical on Sea Urchin gamete harvesting and fertilization. This was followed by a very instructive tour of CIMARQ and its various projects, from seaweed culture (which is the main source of food for Sea Urchins) to the Conger and Cole fish tanks (see below).  This course was unique in that it covered a wide range of developmental models instead of focusing on one or two: Throughout the twelve days of the course we had two days of each: Zebrafish, Xenopus, Planarian, Drosophila and Chick (plus a symposium and a first day tour). While including such a variety of different models may seem too optimistic (especially for just two days of each!), the truth is that the course was a huge success as proved by the fact that most of the experiments were successful. Our day schedule started with lectures and lab work in the morning. Then lunch, after which we spent most of the time in the lab and, after dinner, everyone attended presentations, by students, about their research. This part (the presentations) was a very good innovation this year and, given its success, it will probably continue in future courses. The discussions were very productive, and, from a student’s point of view, it was great having peak scientists listening, criticizing and suggesting experiments for my research. It was also good to share our areas of research between students since it was very different from the casual exchange of area of research in informal gossip. So, on to the course.

This course was unique in that it covered a wide range of developmental models instead of focusing on one or two: Throughout the twelve days of the course we had two days of each: Zebrafish, Xenopus, Planarian, Drosophila and Chick (plus a symposium and a first day tour). While including such a variety of different models may seem too optimistic (especially for just two days of each!), the truth is that the course was a huge success as proved by the fact that most of the experiments were successful. Our day schedule started with lectures and lab work in the morning. Then lunch, after which we spent most of the time in the lab and, after dinner, everyone attended presentations, by students, about their research. This part (the presentations) was a very good innovation this year and, given its success, it will probably continue in future courses. The discussions were very productive, and, from a student’s point of view, it was great having peak scientists listening, criticizing and suggesting experiments for my research. It was also good to share our areas of research between students since it was very different from the casual exchange of area of research in informal gossip. So, on to the course.

Zebrafish module

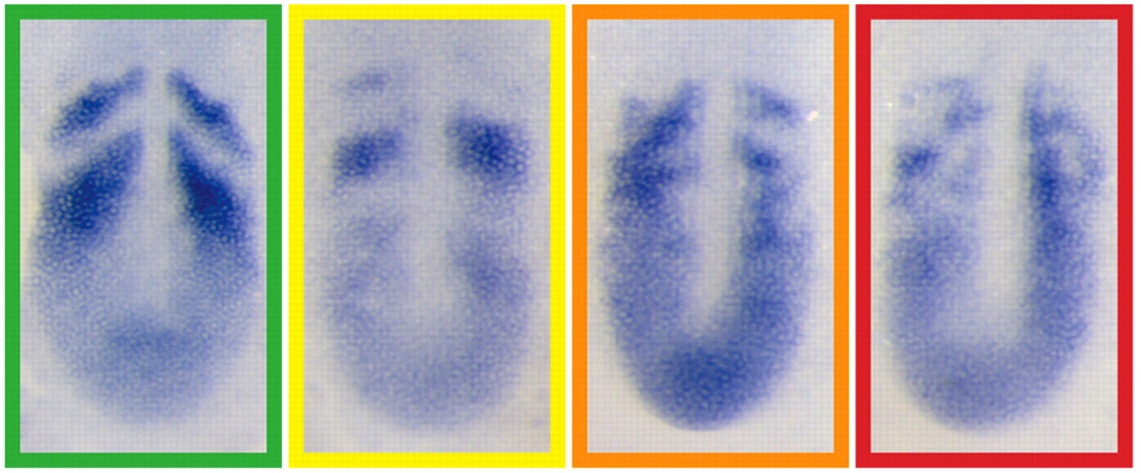

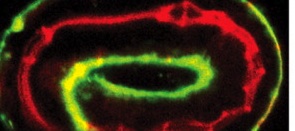

Zebrafish was coordinated by Dr. Kate Whitlock.  The first Lecture was on Zebrafish basics (rearing and genetics) and embryo morphology. We then proceeded to the lab in which work consisted of cataloging the effects of different concentrations of alcohol in zebrafish development by observation under dissecting microscope of live embryo general morphology and craniofacial development. Afterwards, we carried out an immunohistochemistry protocol for the detection of neuron and neural crest markers so as to further characterize the effects of ethanol in early development. To sum up the results, I would say that the message ¨Vertebrate development and alcohol don’t mix¨ was extremely clear: The deleterious effects on general and craniofacial development were patent even without the need for immunohistochemistry. The second lecture by Kate focused on neural crest development and how neural crest cells migrate and interact with the neural tube and placodes to give origin to the olfactory system At the lab, we studied gene expression of three main neuron and neural-crest marker genes (shh, sox10 and six4b) using in-situ hybridization. Finally, we observed fluorescent-tagged transgenic lines and we compared the results with those of immunohistochemistry and hybridization.

The first Lecture was on Zebrafish basics (rearing and genetics) and embryo morphology. We then proceeded to the lab in which work consisted of cataloging the effects of different concentrations of alcohol in zebrafish development by observation under dissecting microscope of live embryo general morphology and craniofacial development. Afterwards, we carried out an immunohistochemistry protocol for the detection of neuron and neural crest markers so as to further characterize the effects of ethanol in early development. To sum up the results, I would say that the message ¨Vertebrate development and alcohol don’t mix¨ was extremely clear: The deleterious effects on general and craniofacial development were patent even without the need for immunohistochemistry. The second lecture by Kate focused on neural crest development and how neural crest cells migrate and interact with the neural tube and placodes to give origin to the olfactory system At the lab, we studied gene expression of three main neuron and neural-crest marker genes (shh, sox10 and six4b) using in-situ hybridization. Finally, we observed fluorescent-tagged transgenic lines and we compared the results with those of immunohistochemistry and hybridization.

Xenopus module

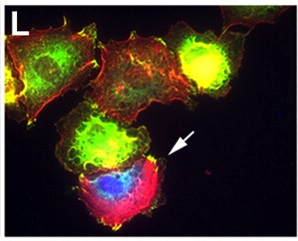

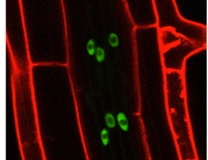

Xenopus was the next chapter in this course and, again, experiments were very successful (albeit with a lot of effort). We began with a lecture from Dr. John  Gurdon on the history of Xenopus as a Development model and classic experiments followed by a focus on the regulation of induction by molecule gradients. In the lab, we tried some of those same experiments ourselves: After a brief introduction by Roberto Mayor on egg collection and fertilization, we injected GFP mRNA into two, four and eight cell embryos. The next step was to create Nieuwkoop recombinants by separating vegetable and animal poles from different embryos and then setting them one against the other so that the vegetable pole would induce growth and mesoderm tissue in the animal pole. The following task was to graft neural crest tissue from GFP labeled

Gurdon on the history of Xenopus as a Development model and classic experiments followed by a focus on the regulation of induction by molecule gradients. In the lab, we tried some of those same experiments ourselves: After a brief introduction by Roberto Mayor on egg collection and fertilization, we injected GFP mRNA into two, four and eight cell embryos. The next step was to create Nieuwkoop recombinants by separating vegetable and animal poles from different embryos and then setting them one against the other so that the vegetable pole would induce growth and mesoderm tissue in the animal pole. The following task was to graft neural crest tissue from GFP labeled neurulas into normal ones. Although it took some practice, after a few hours we successfully observed neural crest cells migrating under the ectoderm. On the second day, Roberto took the stand for a lecture on the post-fertilization phenomena of the Xenopus embryo and on the development and function of the neural crest. The final (and most challenging) experiment was to perform a Spemann organizer graft. After about five or ten minutes of dissection, John Gurdon displayed, with a proud smile, a clean and very neat graft. Although John definitely made it look easy, I had like four or five embryos which attest to the contrary. This was the price of success

neurulas into normal ones. Although it took some practice, after a few hours we successfully observed neural crest cells migrating under the ectoderm. On the second day, Roberto took the stand for a lecture on the post-fertilization phenomena of the Xenopus embryo and on the development and function of the neural crest. The final (and most challenging) experiment was to perform a Spemann organizer graft. After about five or ten minutes of dissection, John Gurdon displayed, with a proud smile, a clean and very neat graft. Although John definitely made it look easy, I had like four or five embryos which attest to the contrary. This was the price of success  however as, although most of us agreed that it was harder than it looked, we managed to come up with several grafts which, at least, looked quite tidy. Due to a power shortage (and consequent rise in temperature of the incubator) we were unable to photograph many of those embryos, but the truth is that we were all very satisfied with our achievements.

however as, although most of us agreed that it was harder than it looked, we managed to come up with several grafts which, at least, looked quite tidy. Due to a power shortage (and consequent rise in temperature of the incubator) we were unable to photograph many of those embryos, but the truth is that we were all very satisfied with our achievements.

Planarian module

Planarian was an interesting module in that it is a relatively new model and that we didn’t focus on embryogenesis but on regeneration instead (although we did  have a very interesting lecture on planarian embryogenesis, which involves very rare and interesting processes). Planarians have unparalleled regeneration capacities and can regenerate a whole organism from a very small portion of the parent planarian. Dr. Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado was the scientist who established planarians as research models and it was great having him! Alejandro’s lecture on the establishment of planarians as regeneration research models and the similarities and differences between regeneration and embryogenesis was astounding. In the lab, we started out by cutting up worms in as many ways as we could think of. Over the following days, we got to see strange or downright weird forms of planarians as they regenerated the parts we had cut off. A second experimental part of this module consisted of dissociating cells, staining with Hoechst and observing the cellular morphology of neoblasts (stem cells) among other cell types. In the third part we observed the differences in target proteins and tissue-specific markers between worms under normal conditions and worms either treated with RNAi or cut in half. I particularly enjoyed taking photos of these last worms showing the progressive regeneration of these systems and comparing the velocity and sequence of events that lead to the new worms. This was one of my favorite modules since I didn’t practically know anything about planarians past what I studied in an early zoology course (which seemed boring at the time) and, now, I can’t read enough about them!

have a very interesting lecture on planarian embryogenesis, which involves very rare and interesting processes). Planarians have unparalleled regeneration capacities and can regenerate a whole organism from a very small portion of the parent planarian. Dr. Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado was the scientist who established planarians as research models and it was great having him! Alejandro’s lecture on the establishment of planarians as regeneration research models and the similarities and differences between regeneration and embryogenesis was astounding. In the lab, we started out by cutting up worms in as many ways as we could think of. Over the following days, we got to see strange or downright weird forms of planarians as they regenerated the parts we had cut off. A second experimental part of this module consisted of dissociating cells, staining with Hoechst and observing the cellular morphology of neoblasts (stem cells) among other cell types. In the third part we observed the differences in target proteins and tissue-specific markers between worms under normal conditions and worms either treated with RNAi or cut in half. I particularly enjoyed taking photos of these last worms showing the progressive regeneration of these systems and comparing the velocity and sequence of events that lead to the new worms. This was one of my favorite modules since I didn’t practically know anything about planarians past what I studied in an early zoology course (which seemed boring at the time) and, now, I can’t read enough about them!

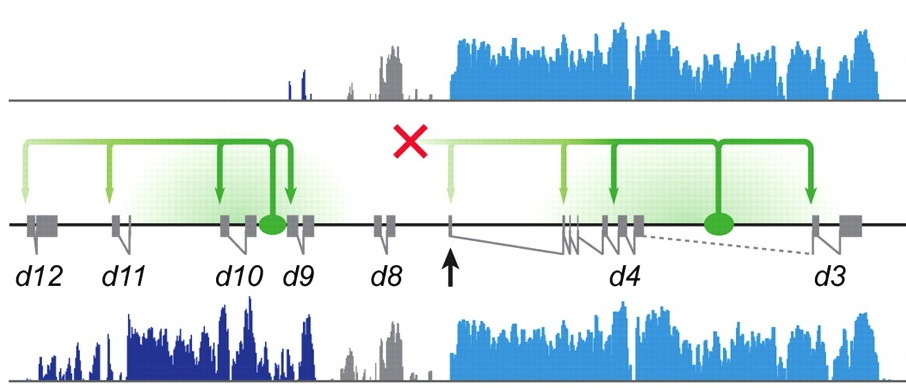

Drosophila module

This module was taught by Drs Trudi Schüpbach, Eric Wieschaus and John Ewer. The first lecture, by Eric Wieschaus, was an interactive talk about fly genetics  and fly crossing. We discussed the screen with which he identified genes that regulated embryogenesis. This was incredible and very instructive, because most of the time, we read about results without taking into account the real work that had to be done to obtain them. In the lab, we carried out several observational experiments: We were given embryos from unknown crosses and had to hypothesize what the parents´ phenotypes were by peeling embryos or bleaching them, followed by immersion in halocarbon oil or fixing in hoyers mountant. Another part of the practical consisted of analyzing mRNA expression (or localization) and observing embryo morphology and movement using transgenic lines. With the help of Trudi Schüpbach, we also dissected ovaries and looked at oogenesis in transgenic lines with either GFP-tagged histones or a membrane-bound GFP. The second day, lead mainly by John Ewer, we focused on later stages of development. John gave a lecture about larval growth, physiology and metamorphosis concentrating on the reorganizing of the neural system during the pupal stage. In the lab we learned how to locate and remove imaginal discs from 3rd instar larvae and we watched the retraction and regrowth of sensory neuron axonal arbors and dendrites during the pupal stage Worthy of mention was Eric’s incredible enthusiasm

and fly crossing. We discussed the screen with which he identified genes that regulated embryogenesis. This was incredible and very instructive, because most of the time, we read about results without taking into account the real work that had to be done to obtain them. In the lab, we carried out several observational experiments: We were given embryos from unknown crosses and had to hypothesize what the parents´ phenotypes were by peeling embryos or bleaching them, followed by immersion in halocarbon oil or fixing in hoyers mountant. Another part of the practical consisted of analyzing mRNA expression (or localization) and observing embryo morphology and movement using transgenic lines. With the help of Trudi Schüpbach, we also dissected ovaries and looked at oogenesis in transgenic lines with either GFP-tagged histones or a membrane-bound GFP. The second day, lead mainly by John Ewer, we focused on later stages of development. John gave a lecture about larval growth, physiology and metamorphosis concentrating on the reorganizing of the neural system during the pupal stage. In the lab we learned how to locate and remove imaginal discs from 3rd instar larvae and we watched the retraction and regrowth of sensory neuron axonal arbors and dendrites during the pupal stage Worthy of mention was Eric’s incredible enthusiasm  with experiments and his loud cheering when the results were revealed (captured in photo). For me, all of the faculty of the course were extremely good professors: Their lectures were very clear and they were all very open to questions or doubts and were very watchful and helpful in the lab. Eric, however, was something else. I can’t actually explain how or why, but, as an example, he took it upon himself to single handedly sharpen most of our pincers to ease embryo peeling and larval dissection!

with experiments and his loud cheering when the results were revealed (captured in photo). For me, all of the faculty of the course were extremely good professors: Their lectures were very clear and they were all very open to questions or doubts and were very watchful and helpful in the lab. Eric, however, was something else. I can’t actually explain how or why, but, as an example, he took it upon himself to single handedly sharpen most of our pincers to ease embryo peeling and larval dissection!

Chick module

The chick embryo was the last model and one of the most challenging, not only because of the complexity of dissection and grafting, but also because of how tired we were. After learning how to set up New cultures, we performed two  experiments: Node grafts and cutting embryos in half. The first experiment, which is analogous to the one done in Xenopus, was intended to demonstrate how Hensen’s Node induces other tissues. In the second experiment we separated posterior and anterior halves of the embryo and observed their development, since the cells of each half reorganized and redefined the embryo axis. As professor Claudia Linker pointed out, in both of these experiments we had an impressive success rate (>90%),

experiments: Node grafts and cutting embryos in half. The first experiment, which is analogous to the one done in Xenopus, was intended to demonstrate how Hensen’s Node induces other tissues. In the second experiment we separated posterior and anterior halves of the embryo and observed their development, since the cells of each half reorganized and redefined the embryo axis. As professor Claudia Linker pointed out, in both of these experiments we had an impressive success rate (>90%), something most of us were very proud of! Additionally, we learned two other very useful techniques which were applied on embryos that were not removed from the egg: Embryo injection with either DNA or a fluorescent label and electroporation of the DNA-injected embryos. Although the success rate was lower, we did get to see some embryos with pretty neat dye labels and even a few good electroporations. Claudio Stern gave two more lectures on the molecular regulation and timing of neural specification and induction and a very interesting and comprehensive one integrating molecular and cellular processes that control, occur during and give rise to gastrulation.

something most of us were very proud of! Additionally, we learned two other very useful techniques which were applied on embryos that were not removed from the egg: Embryo injection with either DNA or a fluorescent label and electroporation of the DNA-injected embryos. Although the success rate was lower, we did get to see some embryos with pretty neat dye labels and even a few good electroporations. Claudio Stern gave two more lectures on the molecular regulation and timing of neural specification and induction and a very interesting and comprehensive one integrating molecular and cellular processes that control, occur during and give rise to gastrulation.

Summing up…

As a student, I was extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in this course. All the faculty were extremely helpful, friendly and sympathetic. In my experience, the closest I can get to scientists of the stature as the faculty of this course is by asking questions at lectures (if I’m extremely lucky). Sharing at least two days with them was very productive and actually giving them) a short presentation was incredible! I was given very good advice on how to guide my research and I also had some very interesting questions (the sort of that great minds usually ask)! Apart from the advantages/tricks/advice I learned for the model I currently work with, this course was very mind-opening: I learned about models that I practically had never heard of before and I feel comfortable about working, for example, with Zebrafish , Xenopus or Chick, three models I never though I would do experiments with! I’m currently thinking about how I can relate my research to one of these models and, hopefully, get my hands dirty working a few months in a lab which uses such models. I would strongly recommend this course for anyone with a strong curiosity and willing to take a look ¨outside the box¨. Please contact me at gersabio@gmail.com if you have any particular doubts about the course or this article and this is the course website: http://biodesarrollo.unab.cl/I wanted to shout out a special thanks for the three organizers: Alfredo Molina, Ariel Reyes and Roberto Mayor, without whom this course would not have occurred, for their dedication and very good will.

As a student, I was extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to participate in this course. All the faculty were extremely helpful, friendly and sympathetic. In my experience, the closest I can get to scientists of the stature as the faculty of this course is by asking questions at lectures (if I’m extremely lucky). Sharing at least two days with them was very productive and actually giving them) a short presentation was incredible! I was given very good advice on how to guide my research and I also had some very interesting questions (the sort of that great minds usually ask)! Apart from the advantages/tricks/advice I learned for the model I currently work with, this course was very mind-opening: I learned about models that I practically had never heard of before and I feel comfortable about working, for example, with Zebrafish , Xenopus or Chick, three models I never though I would do experiments with! I’m currently thinking about how I can relate my research to one of these models and, hopefully, get my hands dirty working a few months in a lab which uses such models. I would strongly recommend this course for anyone with a strong curiosity and willing to take a look ¨outside the box¨. Please contact me at gersabio@gmail.com if you have any particular doubts about the course or this article and this is the course website: http://biodesarrollo.unab.cl/I wanted to shout out a special thanks for the three organizers: Alfredo Molina, Ariel Reyes and Roberto Mayor, without whom this course would not have occurred, for their dedication and very good will.

Germán Sabio

(10 votes)

(10 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

Tags: chick, Developmental Biology, Drosophila, gastrulation, gene expression, international course, neural crest, Planarian, regeneration, Xenopus, zebrafish

Categories: Education, Events, News

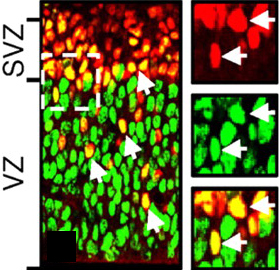

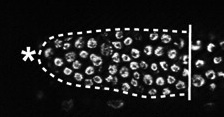

A fully differentiated cell took a fascinating journey to become its present self. For every cell, a precursor cell existed that gave rise to it. And for every precursor cell, a stem cell existed that gave rise to it. Understanding precursor cells is an important part in understanding stem cell biology. Today’s image is from a recent paper in Development that discusses how neuron precursor cell divisions affect development of the cerebral cortex.

A fully differentiated cell took a fascinating journey to become its present self. For every cell, a precursor cell existed that gave rise to it. And for every precursor cell, a stem cell existed that gave rise to it. Understanding precursor cells is an important part in understanding stem cell biology. Today’s image is from a recent paper in Development that discusses how neuron precursor cell divisions affect development of the cerebral cortex.

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Developmental Biology Bingo Game

Developmental Biology Bingo Game