Book Info: The Cell: A Very Short Introduction by Terence Allen and Graham Cowling. Oct 2011. 152 pages. ISBN: 9780199578757 (Paperback) Price: $11.95 /£7.99

Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research.

Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research.

Chapter 1 introduces cells as highly efficient factories capable of maintaining and replicating themselves as well as interacting with and responding to their surroundings. It includes a description of the unifying concepts common to all cells such as cellular components, subcellular organization, and life processes as well as the diversity of cells, their specialized functions and adaptations to various environments. Frequently, generalizations about particular types of cells (prokaryotic or eukaryotic, plant or animal) are intertwined with very specific information such as size of various cytoskeletal filaments.

The following two chapters introduce the subcellular components and describe how these work together to orchestrate the cell’s day-to-day function. The nucleus and organization of the genome as well as a brief description of gene structure are described in their own chapter.

Chapter 4 and 5 discuss various processes of a cell’s life such as division, DNA replication, movement and apoptosis (programmed cell death). Additionally there is a description of various types of specialized, differentiated cells found in multicellular organisms. The focus is primarily on animal cells, however plant cells and bacteria living in extreme environments are briefly mentioned.

Chapter 6 focuses on stem cells in living organisms, both embryonic and adult. Included is the definition of a stem cell, a brief history of the field and a discussion of cancer stem cells.

Chapter 7 discusses cell-based therapies from early attempts to modern applications such as blood transfusions as well as the possibilities that embryonic stem (ES) cell research offers. The ethical debate regarding stem cells is mentioned and there is a discussion of possible applications of stem cells in the treatment of several cellular diseases such as muscular dystrophy and diabetes.

Chapter 8 focuses on the future of cell research. It introduces fields of systems biology, synthetic biology, regenerative medicine and includes a speculative discussion about the possibility of reversing aging in the future.

A small criticism that I have is that despite the short length of the book some errors slipped through the editing process. Most notable is that the description of gene structure incorrectly names the coding sequences “introns” and the non-coding “exons”. Although the correct definition is provided in the glossary this error might confuse a novice student of biology, especially because these terms are counterintuitive.

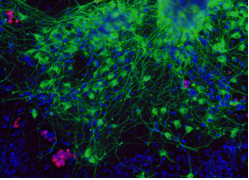

The illustrations, which, except for a few diagrams, are all black and white electron microscope (EM) images showing cell surfaces and subcellular structures. The images are relevant and interesting, but for someone not used to looking at pictures of cells or EM images these might not provide as much information or generate as much interest as the authors intended.

Overall “The Cell” makes for informative and entertaining reading. The concentrated and comprehensive information provided are a perfect refresher to any biologist who wants to be reminded of the basics of cell biology or a novice biology enthusiast who wants to delve into the microscopic world of cells without the intimidation of a textbook. Although the focus is mostly on eukaryotic animal cells, those aspects that distinguish prokaryotes and plant cells are frequently pointed out. The historical anecdotes that accompany descriptions of various discoveries as well as the thought-provoking discussions about the future prospects for the biomedical applications of cell research made this book particularly enjoyable for me. For those readers who find themselves wanting to learn more the authors provide a list of resources for further reading, both books and online resources.

(5 votes)

(5 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(2 votes)

(2 votes) Somites, confocal, epigenetics, germline, stem cell… BINGO!

Somites, confocal, epigenetics, germline, stem cell… BINGO! Stem Cell Biology

Stem Cell Biology Programme Outline

Programme Outline Why should a developmental biologist be interested in a book about the nucleus? Almost 80 years ago, Conrad Waddington put forward ideas about how gene products could regulate development. In modern parlance, much of development is the result of the differential use of the same genome in different cell types and at different developmental stages within the same organism. This originates in the nucleus, where the processes that act upon the genome – transcription, replication, repair – occur. In developmental biology papers it is not uncommon to find a final summary figure in which a signaling pathway ends up pointing into an oval-shaped nucleus, devoid of any structure or organization, save for a linear depiction of a target gene locus. However, the nucleus is not a homogenous space and neither is the genome in its natural nuclear environment arranged in a linear fashion.

Why should a developmental biologist be interested in a book about the nucleus? Almost 80 years ago, Conrad Waddington put forward ideas about how gene products could regulate development. In modern parlance, much of development is the result of the differential use of the same genome in different cell types and at different developmental stages within the same organism. This originates in the nucleus, where the processes that act upon the genome – transcription, replication, repair – occur. In developmental biology papers it is not uncommon to find a final summary figure in which a signaling pathway ends up pointing into an oval-shaped nucleus, devoid of any structure or organization, save for a linear depiction of a target gene locus. However, the nucleus is not a homogenous space and neither is the genome in its natural nuclear environment arranged in a linear fashion. Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research.

Ever since Anton van Leeuwenhoek first peered at a living cell in 1674, scientists have been driven to learn everything they can about these tiny units of life and as a result have been developing ever more advanced tools to observe, describe and manipulate them. In the book “The Cell”, a new addition to the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series, Terence Allen and Graham Cowling undertook an enormous task of distilling several hundred years of cell biology research into 145 pages including 8 chapters, a further reading section, an index, a glossary and 17 illustrations. The result is that an enormous amount of information is presented in pithy vignettes covering everything from the inner workings of the cell up to the complex interactions of cells within multicellular organisms, as well as cellular disease and directions for future research. Benchfly

Benchfly

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)