Here are the highlights from the current issue of Development:

Human embryos make an early transcriptional start

Human preimplantation development is a highly dynamic process that lasts about 6 days. During this time, the embryo must complete a complex program that includes activation of embryonic genome transcription and initiation of the pluripotency program. Here, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte and co-workers use pico-profiling (an accurate transcriptome amplification method) to reveal the timing of sequential waves of transcriptional activation in single human oocytes and embryos (see p. 3699). The researchers (who have developed HumER, a free, searchable database of their gene expression data) report that initiation of transcriptional activity in human embryos starts at the 2-cell stage rather than at the 4- to 8-cell stage as previously reported. They also identify distinct patterns of activation of pluripotency-associated genes and show that many of these genes are expressed around the time of embryonic genome activation. These results link human embryonic genome activation with the initiation of the pluripotency program and pave the way for the identification of factors to improve epigenetic somatic cell reprogramming.

See the post written by the first author of this paper for more information

Worming into organ regeneration

Planarian flatworms have amazing regenerative abilities. Tissue fragments from almost anywhere in their anatomically complex bodies can regenerate into complete, perfectly proportioned animals, a feat that makes planarians ideal for the study of regenerative organogenesis. Now, on p. 3769, Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado and colleagues provide the first detailed description of the excretory system of Schmidtea mediterranea, which consists of internal protonephridial tubules composed of specialised epithelial cells. Using α-tubulin antibodies to stain cilia in the planarian’s excretory system and screens of gene expression patterns in whole mounts, the researchers show that protonephridial tubules form a complex branching structure that has a stereotyped succession of cell types along its length. Organ regeneration originates from a precursor structure that undergoes extensive branching morphogenesis, they report. Moreover, in an RNAi screen of signalling molecules, they identify EGF signalling as a crucial regulator of branching morphogenesis. Overall, these results establish the planarian protonephridia as a model system in which to study the regeneration and evolution of epithelial organs.

Axons lead, lymphatics follow

Given the similar anatomies of vertebrate nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics, it is not surprising that guidance cues such as the netrins, which were discovered as molecules involved in axon pathfinding, also guide vessels. But do nerves and vessels share patterning mechanisms or do axons provide guidance for vessels? The laboratories of Dean Li, Chi-Bin Chien and Brant Weinstein now report that zebrafish motoneurons are essential for vascular pathfinding (see p. 3847). Netrin 1a is required for the development of the parachordal chain (PAC), a string of endothelial cells that are precursors of the main zebrafish lymphatic vessel. Here, the researchers identify muscle pioneers at the horizontal myoseptum (HMS) as the source of Netrin 1a for PAC formation. netrin 1a and dcc (which encodes the Netrin receptor) are required for the sprouting of the rostral primary axons and neighbouring axons along the HMS, they report, and genetic removal or laser ablation of these motoneurons prevents PAC formation. Together, these results reveal a direct requirement for axons in vascular guidance.

Satellite cells: stem cells for regenerating muscle?

Adult vertebrate skeletal muscle has a remarkable capacity for regeneration after injury and for hypertrophy and regrowth after atrophy. In 1961, Alexander Mauro suggested that satellite cells, which lie between the sarcolemma and basement membrane of myofibres, could be adult skeletal muscle stem cells. Subsequent cell transplantation and lineage-tracing studies have shown that satellite cells, which express the Pax7 transcription factor, can repair damaged muscle tissue, but are these cells essential for muscle regeneration and other aspects of muscle adaptability? In this issue, four papers investigate this long-standing question.

On p. 3639, Chen-Ming Fan and colleagues report that genetic ablation of Pax7+ cells in mice completely blocks regenerative myogenesis after cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury and after transplantation of ablated muscle into a normal muscle bed. Because Pax7 is specifically expressed in satellite cells, the researchers conclude that satellite cells are essential for acute injury-induced muscle regeneration but note that other stem cells might be involved in muscle regeneration in other pathological conditions.

Anne Galy, Shahragim Tajbakhsh and colleagues reach a similar conclusion on p. 3647. They report that local depletion of satellite cells in a different mouse model leads to marked loss of muscle tissue and failure to regenerate skeletal muscle after myotoxin- or exercise-induced muscle injury. Other endogenous cell types do not compensate for the loss of Pax7+ cells, they report, but muscle regeneration can be rescued by transplantation of adult Pax7+ satellite cells alone, which suggests that Pax7+ cells are the only endogenous adult muscle stem cells that act autonomously.

On p. 3625, Gabrielle Kardon and colleagues confirm the essential role of satellite cells in muscle regeneration in yet another mouse model. They show that satellite cell ablation results in complete loss of regenerated muscle, misregulation of fibroblasts and a large increase in connective tissue after injury. In addition, they report that ablation of muscle connective tissue (MCT) fibroblasts leads to premature satellite cell differentiation, satellite cell depletion and smaller regenerated myofibres after injury. Thus, they conclude, MCT fibroblasts are a vital component of the satellite cell niche.

Finally, on p. 3657, Charlotte Peterson and colleagues investigate satellite cell involvement in muscle hypertrophy. By removing the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles in the lower limb of mice, the researchers expose the plantaris muscle to mechanical overload, which induces muscle hypertrophy. After two weeks of overload, muscles genetically depleted of satellite cells show the same increase in muscle mass and similar hypertrophic fibre cross-sectional areas as non-depleted muscles but reduced new fibre formation and fibre regeneration. Thus, muscle fibres can mount a robust hypertrophic response to mechanical overload that is not dependent on satellite cells.

Together, these studies suggest that satellite cells could be a source of stem cells for the treatment of muscular dystrophies but also highlight the potential importance of fibroblasts in such therapies. Importantly, the finding that muscle regeneration and hypertrophy are distinct processes suggests that muscle growth-promoting exercise regimens should aim to minimise muscle damage and maximise intracellular anabolic processes, particularly in populations such as the elderly where satellite activity is compromised.

Plus…

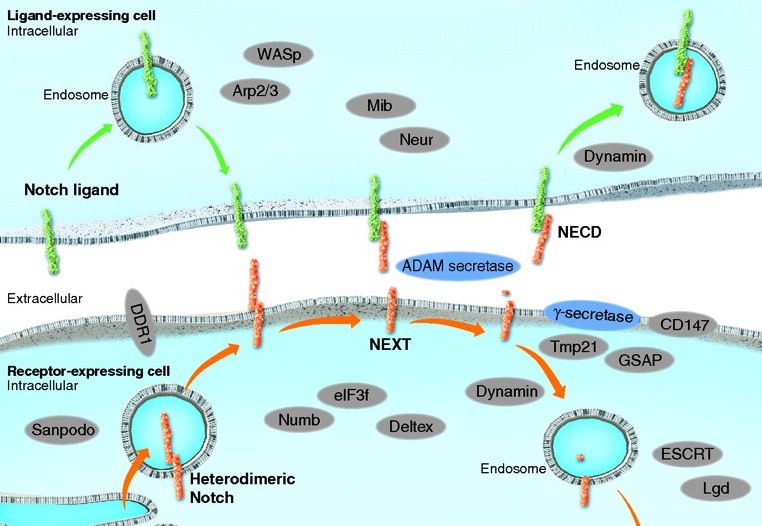

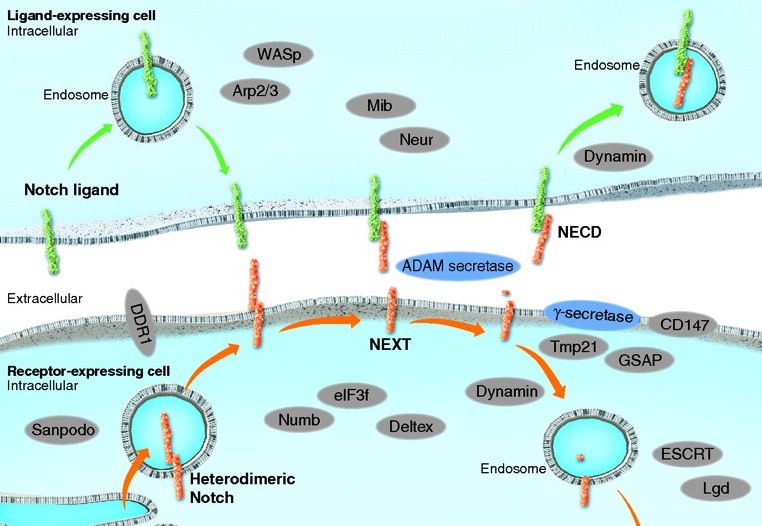

Notch signaling: simplicity in design, versatility in function.

The evolutionarily conserved Notch signalling pathway operates in numerous cell types and at various developmental stages. Here, Andersson, Sandberg and Lendhal review recent insights into how versatility in Notch signalling output is generated and modulated.

See the Review article on p.3593

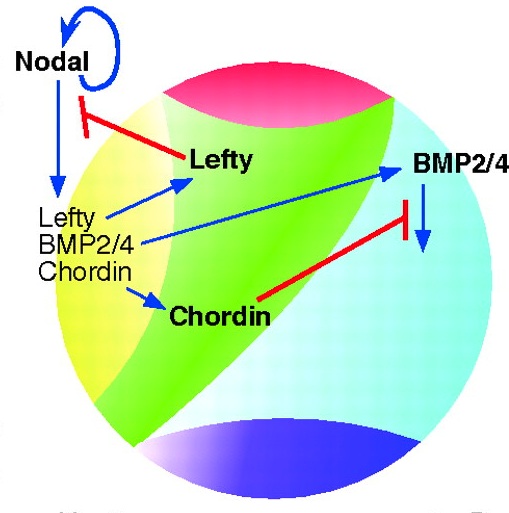

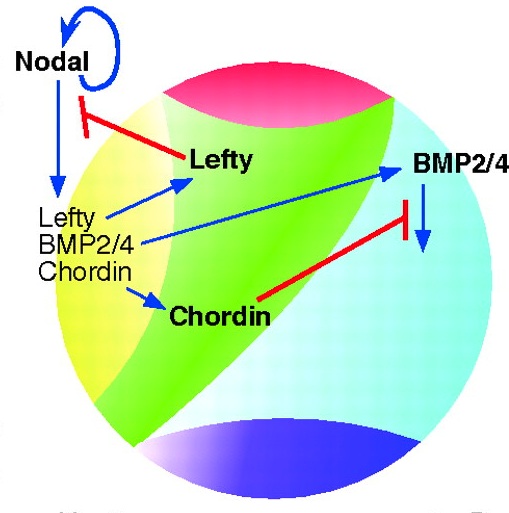

Evolution of nervous system patterning: insights from sea urchin development

Recent studies have elucidated the mechanisms that pattern the nervous system of sea urchin embryos. Angerer and colleagues review these conserved nervous system patterning signals and consider how the relationships between them might have changed during evolution.

See the Review article on p. 3613

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Loading...

Loading...

![]() Vassena, R., Boue, S., Gonzalez-Roca, E., Aran, B., Auer, H., Veiga, A., & Belmonte, J. (2011). Waves of early transcriptional activation and pluripotency program initiation during human preimplantation development Development, 138 (17), 3699-3709 DOI: 10.1242/dev.064741

Vassena, R., Boue, S., Gonzalez-Roca, E., Aran, B., Auer, H., Veiga, A., & Belmonte, J. (2011). Waves of early transcriptional activation and pluripotency program initiation during human preimplantation development Development, 138 (17), 3699-3709 DOI: 10.1242/dev.064741

(9 votes)

(9 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(5 votes)

(5 votes)