Welcome to my report from the 9th Annual ISSCR Meeting in Toronto, 2011. This is the final part, covering the events of day four of the conference (Saturday); Follow these links to read my account of day one, day two, and day three.

Day 4 – Saturday 18th June

There is a great amount of interest in therapies involving the use of stem cells, but unfortunately it would seem that the case has been overstated, as was suggested by Irving Weissman on the first day of the conference. Nevertheless, it was very great to see some fantastic talks during the ‘Therapeutic Approaches to Stem Cells’ plenary, where the research behind already promising therapies was revealed.

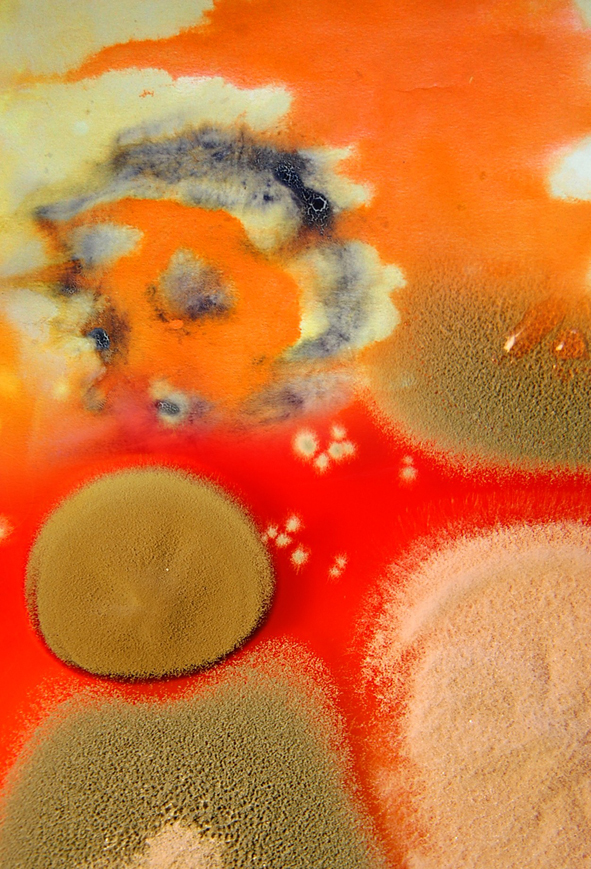

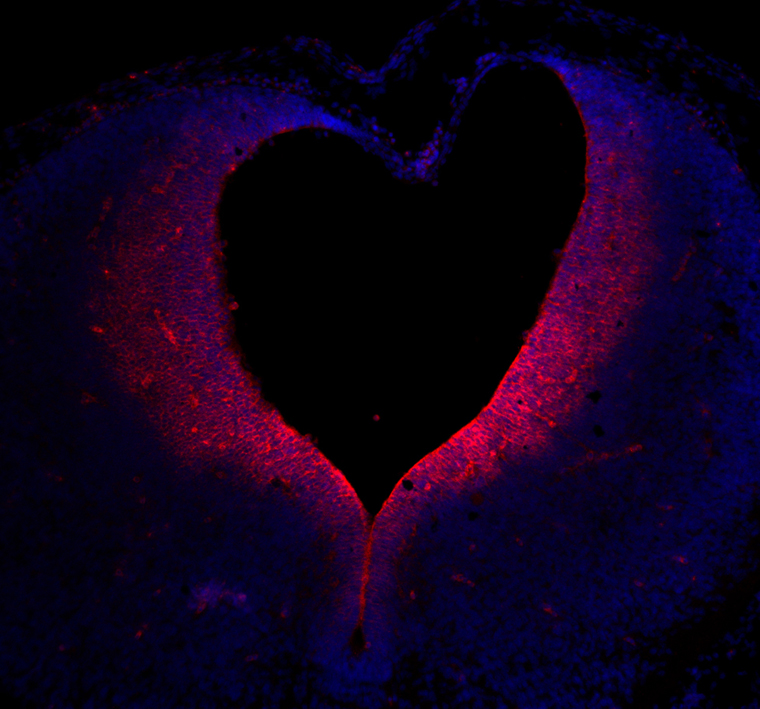

To start off, Leonard Zon (Children’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute at Harvard) presented work studying haematopoiesis in zebrafish, which are used for screening drugs to increase HSC numbers (for exmaple pGE2). Ken Chien (Massachusetts General Hospital) showed his work directing in vivo heart cell fate using modified RNAs, a treatment shown in mice to repair infarcted heart muscle and increase coronary vasculature.

Chris Breuer from Yale School of Medicine described his work with engineering vascular grafts for use in reconstructive surgery. The main problem with using non-living vasculature for repairing congenital heart defects is that once implanted shortly after birth, they don’t grow, and so need to be replaced. Chris and his colleagues have managed to engineer large blood vessel grafts that contain living endothelium (generated from bone marrow derived mononuclear cells) that integrate seamlessly into the recipient’s existing blood vessels. The most interesting part of this reconstruction is that the cells that make up the new vessel, once the biodegradable polymer scaffold has disappeared, are not those bone-marrow derived cells that were originally implanted, but cells that have migrated from the neighbouring blood vessels, akin to how skin wounds heal. One problem that they have encounted when using this in human patients has been the narrowing of the vessel. Whilst macrophage infiltration is essential for the forming of new vessel tissue (in addition to removing the scaffold), it appears that excessive infiltration is the cause of this narrowing. As such, current work which aims to design a ‘cell-free’ graft will have to take this balance into account.

Next, Michele De Luca (University of Modena and Reggio Emelia, Italy) presented amazing work repairing corneal injuries by using stem cells derived from the limbus, a region of the between the sclera and the cornea – video demonstrations of the delicate sugery already being performed on patients was not for the squeamish! Sheng Ding (Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease) gave a talk outling his work identifying small molecules that replace reprogramming factors and increase reprogramming efficiency, with a view to generating functional cardiomyocytes. Finally, renowned journalist Charles Sabine, addressing the ISSCR as a patient’s advocate of Huntington’s Disease, talked frankly about his life dealing with the consequences of his family’s history and his subsequent diagnosis of this condition – an incredibly moving speech which aimed to inspire stem cell researchers to strive for future cures.

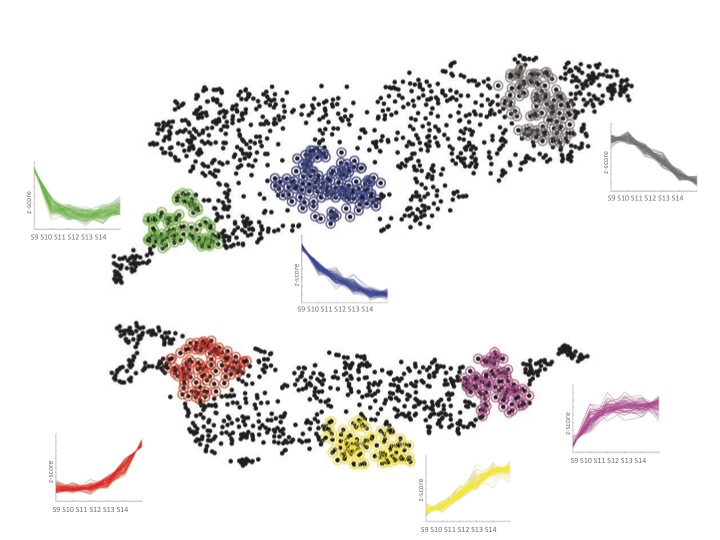

For the final concurrent sessions, I attended the ‘Epigenetic Programming of Stem Cells’ track, which Yi Zhang (University of North Carolina) opened by talking about Tet proteins and the control of DNA methylation in ESCs. Next, Andrew Xiao (Yale) discussed the role of the histone variant protein H2A.X in ESCs, and Kevin Huang (UCLA) discussed his bioinformatics-based research into the regulation of the mESC transcriptome by DNA methylation.

Alessandra Giorgetti from Centre of Regenerative Medicine in Barcelona described her work involving the transdifferentiation of cord-blood derived CD133+ cells towards the neural lineage. This transdifferentiation process, which did not go through a pluripotent stem cell state, required only one transcription factor, Sox2, could be enhanced by using cMyc. The resultant neural progenitor cells gave rise to functional mature motor neurones in vitro and in vivo. Finally, Suneet Agarwal (Boston’s Children’s Hospital) returned to Tet proteins, this time focussing on the role of Tet2 in mESCs and myeloid tumourigenesis.

The final session of the meeting began with the presenation of the first McEwan Centre Award for Innovation to Shinya Yamanaka and Kazutoshi Takahashi, for their pioneering work to generate iPS cells from somatic cells using various combinations of pluripotency related transcription factors. Upon acceptance of the award (which names both senior and junior researchers of discoveries), Shinya described himself as a less than enthuastic physician before resorting to work as a scientist, and also recounted the early days of Kazutoshi’s PhD in his lab, where he consistently made mistakes that I’m sure most members of the audience are very familiar with! Kazutoshi, for his part, self-depricatingly played down his own contribution towards the innovation – “all I did was transfection”. Shinya closed their acceptance speech by expressing gratitude for international support during the aftermath of the earthquake that hit Japan earlier in the year, and extending a warm invitation to next year’s ISSCR meeting in Yokohama.

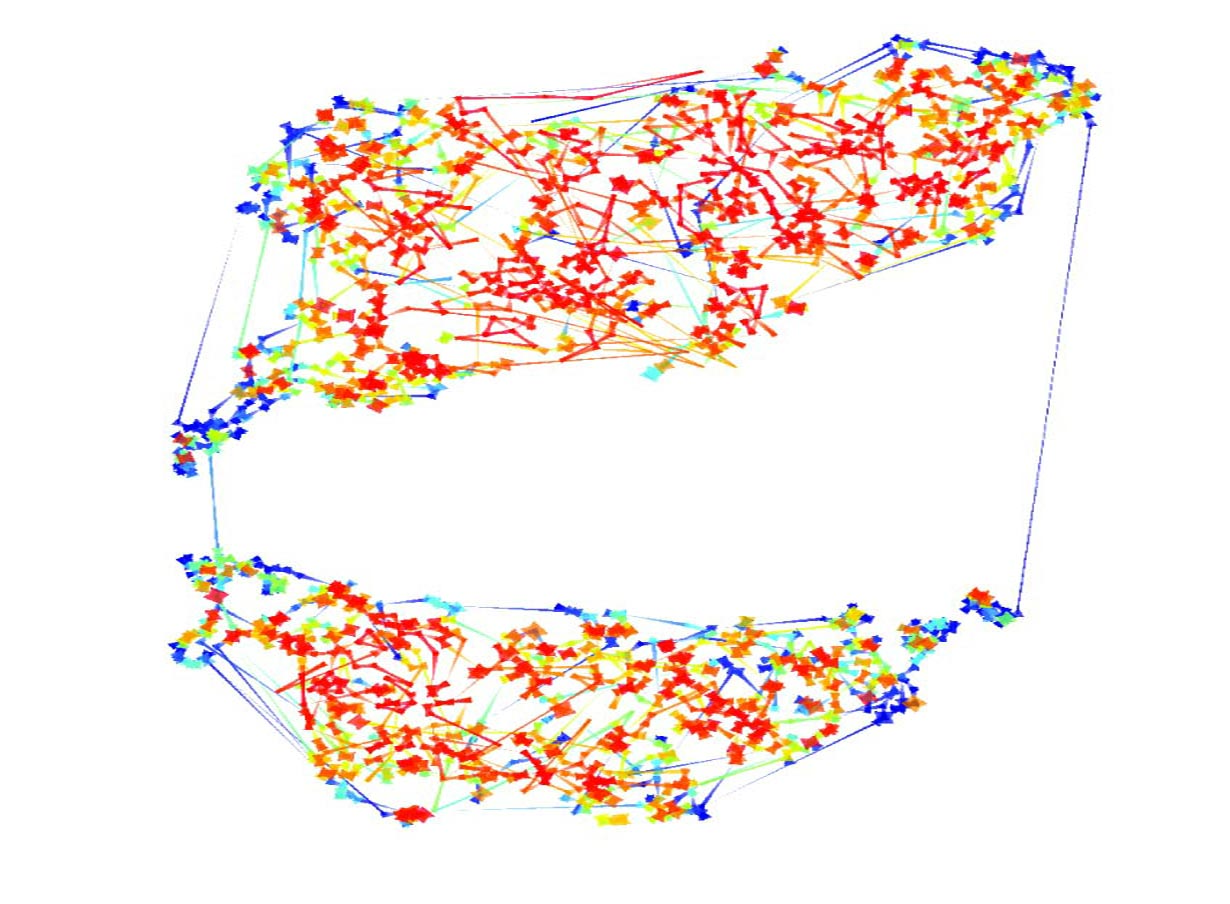

In the closing plenary, ‘Regulatory Networks of Stem Cells’, Rick Young (Whitehead Institute, MIT) presented his lab’s work on the role of Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog in the transcriptional control circuitry of ESCs. Stuart Orkin (Harvard) presented work identifying the components of the Polycomb Repressive Complex-2 (PRC2) and its role in controlling pluripotency in ESCs and cancer. Judi Lieberman (CBR Institute for Biomedical Research) described a genome-wide siRNA screen to identify selective inhibitors of triple negative breast cancer, which unexpected came up with proteosome components. Finally, in the Anne McLaren Memorial Lecture, Nicole Le Douarin (Academie Des Science, France) described her extensive research in the field of neural crest development, identifying the neural crest as a pluripotent organ which contributes cells to every tissue in the body.

And so ends four days of brilliant science. This year’s ISSCR meeting was my first, and it was a great experience, not least for the sense of community that the ISSCR has strived to create. I’d highly recommend anyone involved in stem cell research to head to Yokohama next year (or Boston the year after) for it.

~Richard Berks

PS. As a small cheeky plug, I’d like to point you towards a blog I write (on a regrettably infrequent basis), Coffee & Cake, Pizza & Beer, which has so far concerned itself with life as a PhD student in biological sciences. I hope to have an article about my experience from the ISSCR meeting up soon.

(3 votes)

(3 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(4 votes)

(4 votes) Biology Open is a new journal, launching in September 2011, from The Company of Biologists, publishers of Development, Disease Models & Mechanisms, Journal of Cell Science and The Journal of Experimental Biology.

Biology Open is a new journal, launching in September 2011, from The Company of Biologists, publishers of Development, Disease Models & Mechanisms, Journal of Cell Science and The Journal of Experimental Biology.

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)