DrosAfrica: Background and Workshops

Posted by Isabel M Palacios, on 24 May 2017

Introduction to the DrosAfrica project

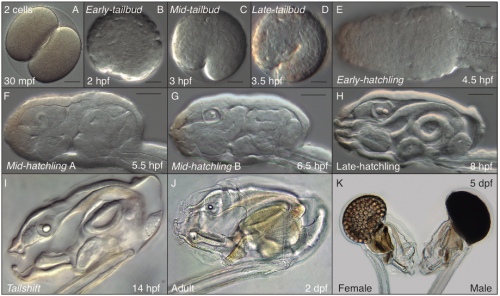

The contribution of scientific research in shaping societies is increasingly significant. However, African researchers make up only around two per cent of the world’s academic research community. One of the central problems for African science is poor quality and quantity of research-based education. We believe that basic scientific research could help developing African nations, and we also believe that Drosophila melanogaster – the fruit fly – can be used as a powerful and inexpensive model system to scale-up and improve both post-graduate education and research output in Africa.

The “DrosAfrica” project (www.drosafrica.org) has the aim of training and establishing a connected community of African researchers with the knowledge to be able to use Drosophila as a model system to study biomedical problems. Historical evidence of the power of Drosophila as a research model comes from Spain in the 80’s (see this piece by Alfonso Martinez-Arias for background) where Drosophila transformed the scientific panorama when resources were limited. With this in mind, we have decided that the first aim of DrosAfrica should be to train well-established African scientists to use Drosophila as a model system to study human diseases.

To date, DrosAfrica has trained 57 scientists from many African countries including South Sudan, Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya and Uganda. These efforts have already paid dividends, as various DrosAfrica alumni and collaborators are using the fruit fly in their own labs, such as Profs. Abolaji and Adedeji, and Drs. Vicente-Crespo, Wuyep, and Nyanhom (Box 1). Critically, these scientists are already training the next generation, with multiple PhD and MSc students in their lab leading biomedical projects using the fruit fly as a model.

We believe DrosAfrica can make a substantial contribution in developing and advancing science for sustainable prosperity in Africa. The mission of DrosAfrica is two-fold. Firstly, to help establish a highly skilled community of researchers capable of using Drosophila as a model system to study biomedical problems. Secondly, to develop Drosophila biomedical units with high-quality research facilities that allow African researchers to train and run projects that will impact the biomedical sciences.

The Workshop Approach

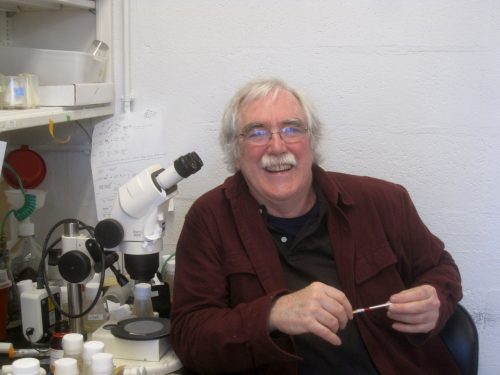

To achieve our goals, we have adopted an approach that centres on carrying out workshops with world-class researches training African scientists at host institutions. Through a collaboration with Professor Sadiq Yusuf, then at Kampala International University (KIU, Uganda), we organised the first DrosAfrica workshop in KIU for African scientists in 2013, followed by others in Uganda, Kenya and Nigeria. The aim of the workshops is to equip African scientists with all the knowledge and tools required to be able to use Drosophila to study biomedical problems. The workshops are organised to be highly practical and interactive, including hands-on laboratory experiments to compliment the lectures. The 20-25 workshop participants learn about the advantages and disadvantages of Drosophila for biomedical research, as well as how to set-up a Drosophila laboratory. Ultimately, and most importantly, the workshop helps participants to improve their critical thinking and to gain further experience using the scientific method.

Another key aspect of the workshops is to facilitate networking, especially among the African scientists that might be ready to implement in their own institutions the research approaches learnt in the workshop. The topic of the workshops is tailored to the research interest of the collaborating institution, and can range from insecticide resistance and host-pathogen interactions to cancer and neurodegeneration. To identify a host institution for a workshop we either directly contact a prospective institution that we think would benefit from our approach, or a scientist that knows about us (occasionally a previous workshop participant) invites us to organise a workshop where she/he works. After initial discussions by skype or phone, we visit the institution and make further arrangements for the workshop, topics and funding.

Our Thanks To

None of the work by DrosAfrica would be possible without the extremely generous help from various organisations and scientists. The Company of Biologists, who has funded various workshop expenses including the microscopes that are essential for Drosophila manipulation, constantly supports DrosAfrica. We would also like to thank the faculty that has helped us in our efforts over the years. The response has always been remarkable with everyone we approached agreeing to help us. We also thank KIU, The Cambridge-Africa Alborada Research Fund, the International Centre for Genetic, Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS), EMBO, and The Wellcome Trust for financial support. We are also thankful to trendinafrica.org, CamBioScience, the Department of Zoology and the University of Cambridge for support, and St John’s, Emmanuel and Pembroke Colleges (Cambridge, UK) for funds.

Anyone that reads this article is encouraged to visit our website (www.drosafrica.org), and think about ways in which they can help, from their own work and time to any advertisement and financial support.

ASANTE SANA

Box 1. Achievements by DrosAfrica alumni and collaborators

- Prof. Amos O Abolaji co-organised and participated in a five-day course at the University of Jos (Nigeria) on the use of Drosophila in Experimental Medicine (2016). In all, about 40 participants attended the event. “My first encounter with this amazing model was during a postdoctoral training at the Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil. Now in Ibadan, so far thirteen M.Sc. students have successfully used the fly for their projects. We now have a Drosophila lab that can conveniently accommodate 20 students.” Prof. Abolaji is hosting our next workshop at the University of Ibadan, July 2017 (http://ibadan2017.drosafrica.org)

- In KIU (Ishaka, Uganda), under Dr. Marta Vicente-Crespo’s supervision (now in St Augustine International University (Kampala, Uganda), two BSc Pharmacy, and two MSc have completed their thesis using Drosophila to study various subjects from toxicity studies to epilepsy and the olfactory system. In addition, she currently supervises three PhD and two MSc students using Drosophila to investigate RNA decay, epilepsy and aging.

- Dr. Ponchang Apollos Wuyep, Associate Professor of Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, Head of Department, Department of Plant Science and Biotechnology, Faculty of Natural Sciences Building, University Of Jos, Nigeria. “My focus is fungal infectious studies. More specifically, to infect Drosophila melanogaster with various virulent Aspergillus sp and then screen for plant compounds that might help the fruitfly to fight the infection…maybe venture into antifungal drug screen. I am working with three students (one MSc, one BSc and one PhD). All these projects got inspired by DrosAfrica”. Dr Wuyep will teach in our 2017 workshop at the University of Ibadan.

- Dr. Steven Nyanhom, Chairman of the Department of Biochemistry (Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology JKUAT, Nairobi) is currently using Drosophila in his research. He participated as Faculty in our last workshop in September 2016 at ICIPE, Nairobi.

- Prof. Ahmed A. Adedeji. Habib Medical School, Islamic University In Uganda (IUIU), Kampala, Uganda. Currently using Drosophila in his research. He has repeatedly participated as Faculty in our workshops, and he will teach in our next workshop at the University of Ibadan, July 2017.

- Mr. Temitope Etibor, former staff of KIU Western Campus, was accepted at the Integrated Biology and Biomedicine PhD program at the Institute Gulbenkian in Portugal. Etibor’s words show that the impact of the workshops goes way beyond the practical skills of working with flies: “The faculty of the DrosAfrica have been very good mentors and wonderful on a personal and career level. I have always been in touch with Martha Vicente-Crespo and Will Wood (members of Faculty) and they have helped me push my career forward in order to make me an excellent scientist. Through the many things I have learnt, I was able to apply for and successfully obtained an FCT PhD Scholarship in Portugal with the support of the aforementioned Faculty. I am so happy to be an Alumnus of the DrosAfrica initiative and I hope they keep receiving funds to aid the cause of research progress in Africa”.

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(16 votes)

(16 votes)