In a vague sense it was a move that was planned all along. After all I did tell my friends and family when I left in 2001 for UPenn to do my PhD there that ultimately I will return. Yet when the moment and the opportunity came, suddenly the idea to move back to Budapest felt anything but a well-planned, cool-headed decision.

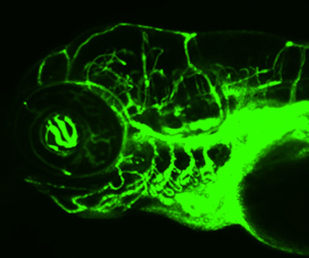

It would be nice to say that the country that gave George Streisinger (the godfather of zebrafish genetics) to the world, was rolling out the red carpet, to welcome freshly trained, young and enthusiastic zebrafish researchers, but that would not be quite an exact representation of reality.

Most Hungarians who dipped their toes into the waters of zebrafish research did so abroad, and the overwhelming majority stayed there. This, of course, means that most research centers and academic institutions do not really have the infrastructure to do zebrafish genetics (indeed, I know only of a single place in Hungary, where a world-class zebrafish facility is being in use), which makes the beginning of one’s effort to build and independent zebrafish research group an even more arduous and stressful task.

During our training time, we (aspiring scientists) all dream of the moment when we will finally become masters of our own, and can start following our own instincts. Yet, after the warm welcome and back patting, when the sense of novelty fades away and you find yourself in an essentially empty room, suddenly it becomes clear that you are in an anything but enviable situation. Yes, you are free to follow your instincts, but there are some big strings attached to this freedom: you need to find the ways and means to fund your pursuit of scientific truth. This is never easy, and trying to succeed in it while the Great Recession of our time is squeezing budgets across the globe is especially frustrating.

So, there I was in mid-2009, as a young faculty member at my former alma mater, the Genetics Department of the Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), with a firm backing from the head of Department and a small return-grant to finance my short-term work. The coming months were anything but straightforward.

If your work relies on model animals, the most important thing is to house them well. As mentioned before, zebrafish wasn’t exactly the animal model of choice for previous generations of scientists at my institute, so there was no designated facility to keep them. Therefore, my new life began with a long (and sometimes desperate) scramble to find a place for my fish lines. During this period I remembered umpteen times an anecdote that I heard at a UCL Departmental Seminar from Hitoshi Okamoto. In the early days of zebrafish research he did not have a designated fish facility so he was forced to keep his animals in tanks in the Institute’s toilet, a condition mockingly described by him as “standard lavatory conditions”.

At the beginning my own fish “facility” was not that different from Okamoto’s: half a dozen plastic tanks bought at the local pet shop, on the top of a small bench. This was a far cry from the immense and well-oiled fish facility of UCL, to which I got accustomed during my post-doc years, but I convinced myself that this was only a transitory situation. Today my group has dozens of fish lines in a separate, temperature-controlled room of our institute’s animal facility. Obviously nothing at UCL’s scale, but still, a huge change. It was a slow but steady progress to get here, all it took was patience, resolve and outside support.

But there’s the catch: as months (and ultimately years) pass by, you realize, that patience and resolve are quite subjective concepts and from a different perspective they might seem like baffling and pointless stubbornness. Things seldom work out as easily as originally imagined, and there will be times when you start to question your judgement, whether it was really a sane idea to move back and/or to start doing fish research from scratch. When all this happens to the backdrop of continuous turmoil and funding cuts in the Hungarian higher education system, one can find himself extremely nostalgic for the safety and predictibility of the post-doc years.

By my second year at ELTE, faculty meetings with the Dean and the Head of the Institute became frustratingly predictable: we were told every time that there were further cuts coming in the university budget, which was the price we had to pay in order not to lay off dozens of people, but we should have taken the opportunity and do more with less. Though there was no question that the people in higher positions (most often scientists themselves) were sincere in their belief that there were efficiency gains to be made within the school (and that was certainly true, to some extent), after a while one couldn’t help but recall David Simon’s maxim: claiming that you can do more with less is a favoured pastime of accountants, but in fact you do less with less.

While university employees were repeatedly told that the reason for the cuts is the dire situation of the budget, people started to note that funding for sports, especially football was going through the roof. This bred a lot of enmity against football, and although science funding lately stabilized somewhat even in Hungary, many people still bear a grudge against lavish stadium-building schemes.

Even without all these “vis maior” circumstances, starting a zebrafish lab at a place where people were not familiar with its advantages would have required a “build it and they will come” type of bravado. From the beginning I repeatedly told myself that there would be also advantages of being the first at something: benefits could come by collaborating with other Hungarian researchers who would like to take advantage of the zebrafish model. In the initial period this became something of an article of faith for me, and, thankfully, I was proven right. After a slow start, when I was busy building networks, the offers for collaborations did start to trickle in. So much, that in the past few months, for the first time since moving home, I started to feel that I’m reaching my limits, and taking on more tasks would be a bad idea.

Nevertheless each new collaboration took me on an exciting new scientific journey and opened up new possibilities. I learned a lot, for which I’ll be always very grateful to all the people who trusted me with their projects, and supported our common endeavours with reagents and advice. And if I’m at handing out kudos, there’s one person who should get special mention: I want to echo my former colleague, Kara, in recognising how much our former post-doc mentor, Steve Wilson supported us, even after we left his lab.

One question I (still) often get is whether I came to regret my decision to move back. This is a complicated thing, and I would have given a somewhat different answer a year ago, and most likely my answer will not be exactly the same in a year’s time. With all my current knowledge, looking back to my 2009 self, I can certainly see that I was very naive, indeed. Truth to be told, the decision to move was made primarily by non-scientific reasons, but as I explained above, there was a clear scientific silver lining as well. Nevertheless, at this particular moment, I would say that taken all together, coming back was worthy. After all Budapest is a great place to be and I’m fortunate enough to live a good life with my family in one of the best spots the city can offer. Science funding is thrifty, but, as I said above, having great collaborators and colleagues makes a huge difference (plus there’s always the hope, that the funding situation will get better, sooner or later). And the more students pass through my lab to end up working with zebrafish in other great European labs, the more I feel that I’m able to make a difference and contribute something to both science and society. Whether that is with or against the odds, will be up to others to tell.

(10 votes)

(10 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) On p.

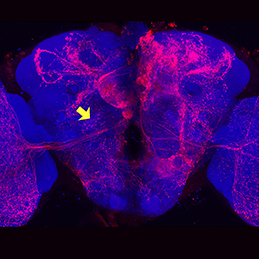

On p.  The role of Notch signalling in pericyte development is also investigated by Raphael Kopan and colleagues (p.

The role of Notch signalling in pericyte development is also investigated by Raphael Kopan and colleagues (p. Neuronal subtype specification is regulated by the coordinated action of transcription factors. Any one factor may be expressed in multiple subtypes, but specification is achieved based on the precise combination of factors and is therefore context dependent. In this issue (p.

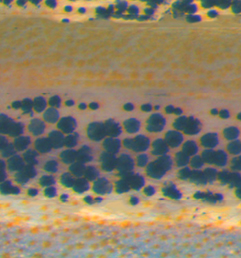

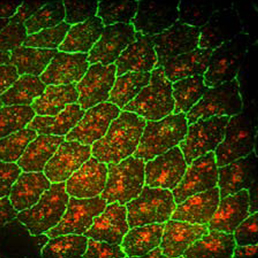

Neuronal subtype specification is regulated by the coordinated action of transcription factors. Any one factor may be expressed in multiple subtypes, but specification is achieved based on the precise combination of factors and is therefore context dependent. In this issue (p.  The striped pattern of the zebrafish skin offers an excellent model system in which to study biological pattern formation. Previous studies have shown that the interactions between melanophores and xanthophores are crucial for pattern formation, but little is known regarding the molecular mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon. Now, on p.

The striped pattern of the zebrafish skin offers an excellent model system in which to study biological pattern formation. Previous studies have shown that the interactions between melanophores and xanthophores are crucial for pattern formation, but little is known regarding the molecular mechanisms that regulate this phenomenon. Now, on p.  Neuronal diversity in Drosophila is generated by the temporal specification of type II neuroblasts (NBs) and their progeny, the intermediate neural progenitors (INPs). Multiple transcription factors are expressed in a birth order-dependent manner within each INP lineage, but whether this temporal patterning gives rise to discrete neuronal sets from each individual INP cell is unclear. Now, on p.

Neuronal diversity in Drosophila is generated by the temporal specification of type II neuroblasts (NBs) and their progeny, the intermediate neural progenitors (INPs). Multiple transcription factors are expressed in a birth order-dependent manner within each INP lineage, but whether this temporal patterning gives rise to discrete neuronal sets from each individual INP cell is unclear. Now, on p.  Dorsal closure is a morphogenic process that involves the interplay of mechanical forces as two opposing epithelial sheets come together and fuse. These forces impact cell shape and the rate of morphogenesis, but the molecular pathways that translate mechanical force into phenotype are not well understood. Now, on p.

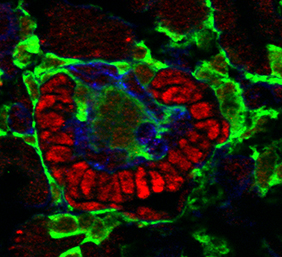

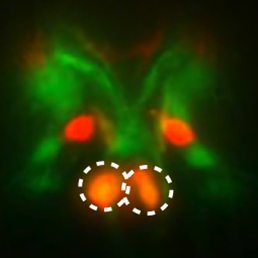

Dorsal closure is a morphogenic process that involves the interplay of mechanical forces as two opposing epithelial sheets come together and fuse. These forces impact cell shape and the rate of morphogenesis, but the molecular pathways that translate mechanical force into phenotype are not well understood. Now, on p.  Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are the precursors of sperm and eggs, which generate a new organism that is capable of creating endless new generations through germ cells. Here, Magnúsdóttir and Surani summarise the fundamental principles of PGC specification during early development and discuss how it is now possible to make mouse PGCs from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, and indeed somatic cells if they are first rendered pluripotent in culture. See the Primer on p.

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) are the precursors of sperm and eggs, which generate a new organism that is capable of creating endless new generations through germ cells. Here, Magnúsdóttir and Surani summarise the fundamental principles of PGC specification during early development and discuss how it is now possible to make mouse PGCs from pluripotent embryonic stem cells, and indeed somatic cells if they are first rendered pluripotent in culture. See the Primer on p.  In their Development at a Glance article, Centanin and Wittbrodt provide an overview of retinal neurogenesis in vertebrates and discuss implications of the developmental mechanisms involved for regenerative therapy approaches. See the poster article on p.

In their Development at a Glance article, Centanin and Wittbrodt provide an overview of retinal neurogenesis in vertebrates and discuss implications of the developmental mechanisms involved for regenerative therapy approaches. See the poster article on p.  (13 votes)

(13 votes)