SciCommConnect: A masterclass in how to deliver your message in the spoken or the written word

Posted by Alex Neaverson, on 30 August 2024

[This report is co-authored by Alex Neaverson, Rachel McKeown and Anna Guixeras Fontana.]

The clock struck 1PM in the UK, the Zoom room opened, and in flooded over 50 scientists. All were drawn together by a passion for effective science communication and were here to sharpen their skills. It was time for the inaugural SciCommConnect workshop, a collaboration between the three community sites of The Company of Biologists (FocalPlane, The Node and preLights).

Though hosted from the UK, this was truly science without borders. Participants tuned in from as far apart as Seattle, USA and Melbourne, Australia. The fact that some were joining as early as 5AM and as late as 10PM local time showcased just how dedicated and engaged the participants were to science communication, which only became more apparent as the event progressed.

With all participants settled and eager to dive in, our hosts welcomed us to the first SciCommConnect event. Launching straight in, we began with a few tips and tricks on the spoken and the written word from two true science communication pros.

What do your research and raw vegetables have in common?

As scientists, we understand our work is of vital importance to us and those in our community. Your immediate motivation is probably your thesis, that conference talk, that paper, or that grant proposal. But how often do you take a step back to see the bigger picture – what are we, as biologists, working towards as a sector? This is what Jamie Gallagher, award-winning freelance communicator, calls the “collective endeavour”; learning how to frame your research in a way that the general public can understand and appreciate is a skill we should all aim to harness.

But why should we care about what the public think of our research? Jamie posed this question to the audience and it produced many insightful answers, including:

- People have a right to knowledge

- To help prevent the spread of misinformation – openly sharing accurate information helps the public put their trust in scientists

- To share the information relevant to human health and medicine

- Presenting our science to wider audiences can help to de-bunk these stereotypical views about what a scientist should look like.

- The public indirectly fund a lot of our research through taxes

How do we go about turning our data into an interesting, engaging, and comprehensible presentation? Consider your research to be the equivalent of raw vegetables: healthy and good for all of us, but not everyone enjoys consuming them. One way of making people eat them is to cut them into bite-sized pieces – the same can be said for our research. Even better, is to cook the vegetables and add some herbs and spices, creating a delicious meal. In the context of a scientific presentation, the herbs and spices are the extra bits that add ‘flavour’: these include things like emotion, storytelling, pauses, analogies, questions, and varying the tone and pace of your speech. You must be careful though – just as adding too much spice can ruin a meal, adding too many of these flavour elements can ruin your presentation.

Imagine your grandma in the audience

The thought of presenting to a large audience conjures up feelings of anxiety and dread in many of us. Jamie talked us through his top tips for delivering a great scientific presentation, some of which I found quite surprising, as they challenged my preconceived ideas about what an effective presentation should include:

1. Introduce yourself the same way every time – knowing exactly what you’re going to say at the beginning will help to calm your nerves, so take the time to rehearse this part.

2. Nerves are normal, and only become a problem if others can tell that you are nervous. Some tips for dealing with nerves include speaking slower than you think; taking a sip of water to give your thoughts time to catch up; telling yourself you’re excited, not nervous; and my favourite – imagining your grandma cheering you on in the audience!

3. Eye contact is not the pièce de résistance for an engaging presentation. The model for good communication is inherently ableist, and doesn’t account for those who are neurodivergent or disabled. These tropes should be challenged, as they do not take away your ability to communicate effectively.

4. Instead of making written notes for each slide of your presentation, consider recording yourself talking, then transcribing it into text to create a more natural sounding script.

5. A general audience will not care about your data – only about what it means. Take the time to re-frame your findings in a way they will understand, and share only as much as is absolutely necessary.

Over to us – Three-minute research talks

After absorbing all of Jamie’s expert advice on presenting, the ball was then placed in our court. Twelve back-to-back research presentations, just three minutes each. In that time, we had to showcase not only what our research is about, but do so in an accessible and engaging way. Let the three-minute research competition begin!

Each participant was armed only with a single PowerPoint slide, but this by no means limited their ability to communicate. Their scientific stories were brought to life verbally in short presentations where each put into action some of the points we’d all been discussing earlier in the programme. Similes and metaphors were used to great effect, with the brain being compared to the contents of your fridge, tissue movements to toothpaste and the cellular environment to a well-known movie franchise (The Matrix). Emotive and personifying language were particularly powerful techniques to drive home the importance and significance of the projects – think of ‘healing a broken heart’ and cells having ‘social’ and ‘lonely’ personalities. Short, impactful sentences, often to summarise or conclude, left lasting memories in the audience. ‘I’m imagining a world without osteoarthritis’ – now we’re imagining it too.

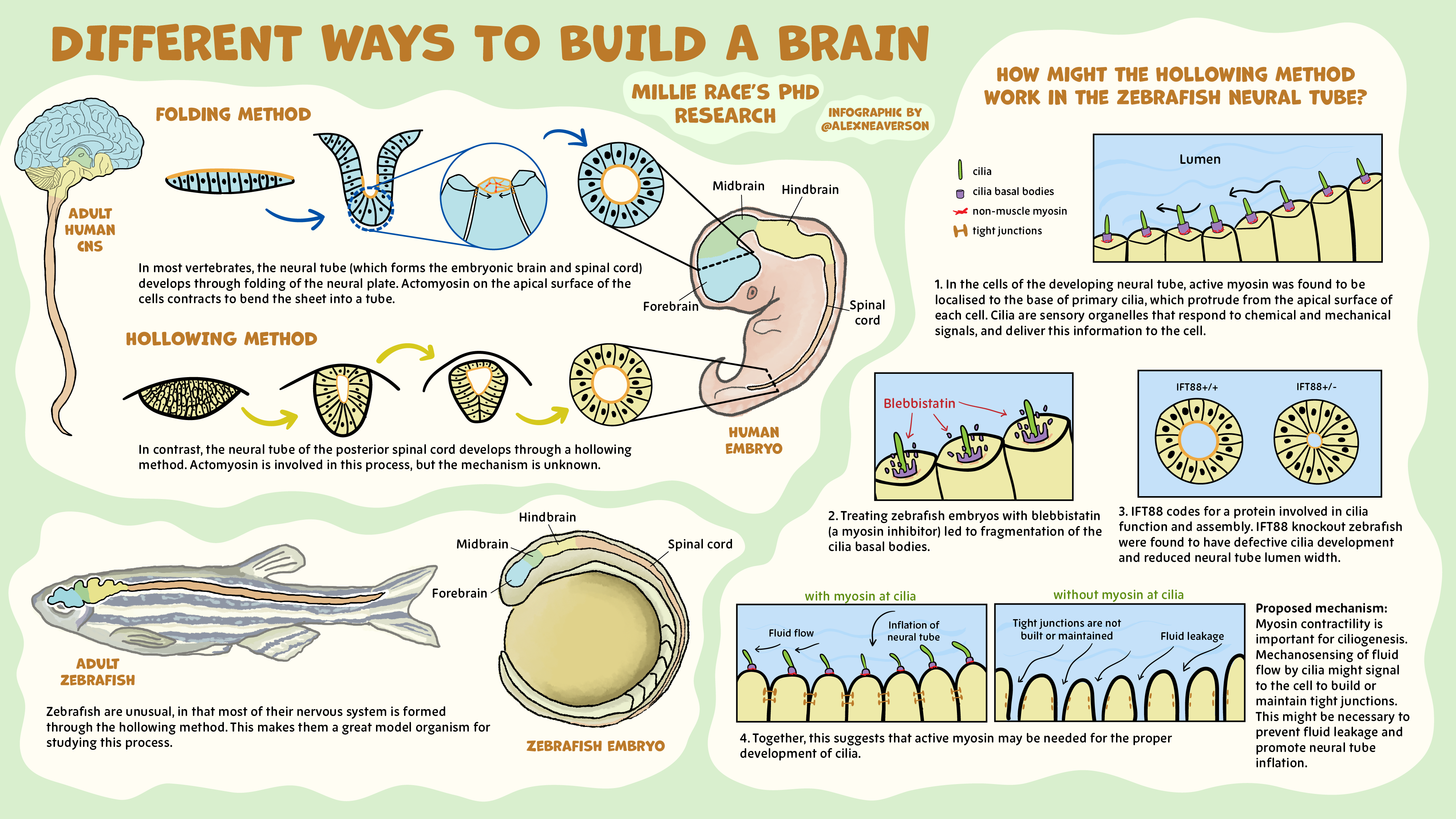

The topics covered were incredibly diverse, but it was fascinating to see common threads emerge as the competition progressed – some were united by their love of zebrafish, others by their fascination with the cytoskeleton. The presentation structures also shared some key elements – opening with an introduction to the wider field, establishing how their own research contributes to it, and rounding up with the overall significance of the work. Jamie, who moderated the competition, was so engaged by the presentations that he could not help but ask questions to each participant after their time was up. His eagerness to dive more into the story was a sure sign that the audience had effectively been captured. The enthusiasm that each participant brought to the stage was infectious, and by the time the competition drew to a close, it felt as if no time at all had passed.

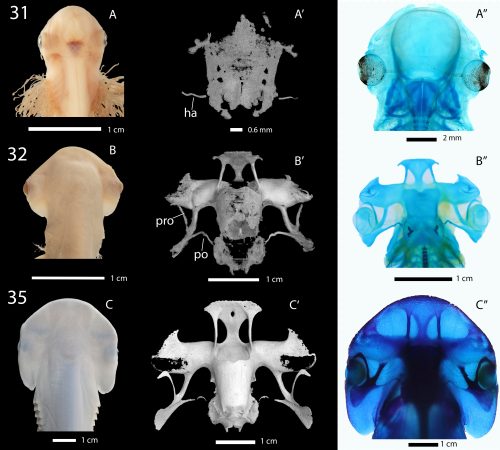

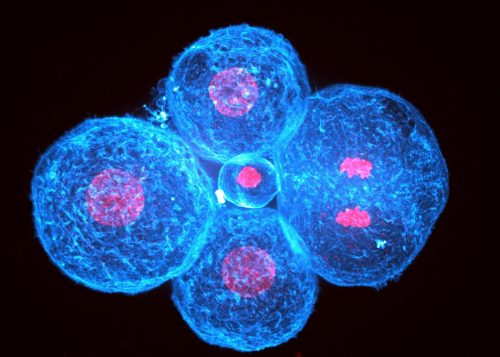

From twelve competitors, two emerged victorious, one chosen by Jamie and the other by audience vote. The worthy winners both delivered fantastic presentations, accompanied by visually striking slides (one being hand-drawn by a clearly talented digital artist, the other boasting stunning microscopy images). Despite this, all talks were highly praised not just by the event hosts, but by all of the fellow participants. The Zoom chat box was flooded with compliments and positivity, with all of us cheering each other on. As a result, by the time the competition drew to a close, we all felt like winners.

The 5 Rules of Fight ClubDevBiolWriteClub

After learning all about how to give an engaging scientific talk, the second half of the event focused on another form of science communication — writing. John Wallingford, professor at UT Austin and a regular contributor on The Node, shared some insights on how we can improve as science writers.

The first (and second) rule of DevBiolWriteClub is to Do The Work. As with any hobby or skill, you cannot expect to improve your writing without practice. This should be intentional – set aside time each day to write, either setting yourself a word limit or a timer. Surprisingly, this was a new concept to me, as someone who has only ever written with a specific goal in mind – a report, an article, a paper – and never purely for the sake of writing.

The third rule is to Revise and Edit: Again, and Again and Again. You will likely have many versions by the time you are finished writing – keep track of these carefully, and never permanently delete anything! You never know when you might want to come back to something you wrote earlier.

The fourth rule is to Read with Intent. So much of how we write is influenced by what and how we read. For this reason, plan to read every single day, and read widely – not just papers, but novels, poetry, comics, or whatever interests you. While you read, reflect on what kind of writing is most and least effective for its purpose.

The fifth rule is: You Cannot Do It Alone. Writing may seem like a lonely endeavour, but it doesn’t have to be. In fact, getting involved with writing groups or having a writing buddy can be very effective in providing accountability and feedback. Normalise sharing your rough first drafts with friends and colleagues – most people do not share their work until they think it is perfect, but by this point you will be attached to it and less receptive to feedback.

Over to us – Writing sprints

After we were all inducted into the DevBiol Write Club, it was our turn to put the writing tips from John into practice.

The collaborative writing sprint at SciCommConnect brought together diverse groups of participants, each of them focusing on eight critical topics in science communication and dissemination. The participants were split into eight breakout rooms on Zoom and over a dedicated hour, each group worked intensively to draft articles on their respective subjects. These subjects include 1/ Communication between Developmental Biologists and the Public, 2/ The Importance of Model Organism Databases, 3/ SciCommConnect Workshop Report, 4/ Sci-Comm “Behind-the-Scenes”, 5/ Science Writing & AI, 6/ Open Science & Preprints, 7/ AI in Microscopy and 8/ Frugal Microscopy.

The authors of this SciCommConnect report, that you, the reader, are reading now, formed one of the writing sprint groups. Within the hour, we drafted a report providing an overview of the SciCommConnect workshop, summarising key presentations and interactive sessions.

To find out how other writing sprints went, we reached out to the other participants after the event. The Node groups focused on producing posts about ‘Communication between Developmental Biologists and the Public’ and ‘The Importance of Model Organism Databases’. Joyce Yu, who led the first group, reflected, “The topic was very broad, and we all had many ideas, but we managed to narrow down the scope of the article and come up with the different sections of the piece.” Similarly, Beatrice and Mansi, participants from the second group, shared, “We have now drafted a piece calling for the continued support of Model Organism Databases. We’re still editing it.” We look forward to seeing their finished articles on the Node soon.

Meanwhile, one of the preLights writing groups worked together to draft a preLights post about a preprint on SciComm ‘Behind the scenes’. The moderator of this group, Martin Estermann, said, “My first attempt at moderating a preLights writing sprints exceeded my expectations; it involved engaging discussions on the status and value of science communication and produced an almost complete preLights post within an hour. This was definitely a collaborative effort.” You can now read their finished preLights article.

In a similar way, the other preLights writing groups created preLights articles on ‘Science Writing & AI’ and ‘Open Science & Preprints’ both of which are now available to read on preLights. Jennifer Ann Black, the moderator of one of these groups, reported, “Together, we enjoyed a constructive session chatting over the use of AI in science. For or against it, AI is here to stay, and we need to find ways of accommodating it.” Reinier Prosee, who led the group on Open science and preprints, added, “We exchanged some relevant personal experiences and discussed a preprint showing that Open Science practices can lead to a higher visibility of research papers. We all agreed though that the potential benefits of adopting Open Science practices go beyond citation metrics.”

Finally, the two FocalPlane writing groups explored the impact of artificial intelligence in microscopy and the concept of ‘frugal microscopy’. Helen Zenner, who led the AI in microscopy group, noted, “It is a huge topic, but we have a few ideas of how we can present our discussion on FocalPlane, so look out for our future posts!”

The collaborative writing sprint at SciCommConnect showcased the power of teamwork in science communication. By bringing together experts and enthusiasts from various fields, the sprint not only produced insightful reports but also strengthened the community’s commitment to effective and inclusive science communication. As the reports are finalised and shared on The Node, preLights, and FocalPlane platforms, they will contribute valuable perspectives and knowledge to the broader scientific community.

Final thoughts

SciCommConnect brought together a group of ~50 like-minded individuals from across the world to share their research and learn how to improve their skills in doing this. Something that was clear from the outset was just how supportive an environment can be created, even over Zoom – each 3 minute research talk was followed by dozens of messages giving praise to different aspects of each talk. It is difficult to anticipate the level of engagement that you’ll get in online workshops, but in this case it truly felt like the presenters were talking to a group of friends. Science is international, yet opportunities to network with researchers from across the world are relatively infrequent and can sometimes depend on opportunities to travel to conferences. Online events enable us to be brought together with far fewer financial and environmental caveats. While many online seminars are passive in nature, SciCommConnect shows how active engagement and audience participation can, with a little forethought and planning from a dedicated organising team, be enabled. A strong sense of community was cultivated, despite the audience stretching over almost 10,000 miles.

Interviews with 3-minute talk participants:

Published posts from writing sprints:

An analysis of the effects of sharing research data, code, and preprints on citations

Model Organism Databases are more than just repositories

More posts and interviews coming soon! Watch this space 👀

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)