Meet the Node correspondents — Alex Neaverson

Posted by the Node, on 29 February 2024

Alex Neaverson is a third-year PhD student at the University of Cambridge, studying regeneration of the Hensen’s Node in chick embryos. Alex is a keen artist and has recently got into scientific illustration while doing an internship at a research charity. As a Node correspondent, she plans to use her artistic skills to create illustrated career timelines of developmental biologists and draw graphical summaries to highlight research conducted by different teams around the world.

Congratulations on being selected as one of our new correspondents! What made you decide to apply to become a Node correspondent?

I’ve known about the Node since I started my PhD in 2021. The Node’s a great resource for bringing developmental biologists together. I really like how there’s a mixture of scientific articles and opinion pieces, and I like the ‘Lab meeting’ posts where you get to know all the different labs. I especially like the SciArt profiles. I love seeing my two big passions — biology and art — mixed together, sometimes in really unusual ways. I’ve always kept art and science separate in my life, where science has been my job and art has been my hobby. But I recently started getting into scientific illustration. I thought considering the Node publishes the SciArt profiles, you might be open to something slightly different from a Correspondent. Maybe you’d like to have someone who can create illustrations as a means of communicating science, instead of purely writing text-based articles. I deliberated over it for a while, but I spoke to my PI and he thought it was a great idea, so I took a chance and clearly it paid off!

How did you get into scientific illustration?

Scientific illustration is something that is very new to me. Art has always been a hobby. I love painting people and animal portraits. I have only started doing scientific illustration during my internship with Alzheimer’s Research UK (ARUK) last year. As part of my PhD course, I had to do a 3-month internship. There was an internship fair and while most organisations had very specific projects in mind, Jorge from ARUK’s Research team was very open to ideas and said that my project could depend on my interests.

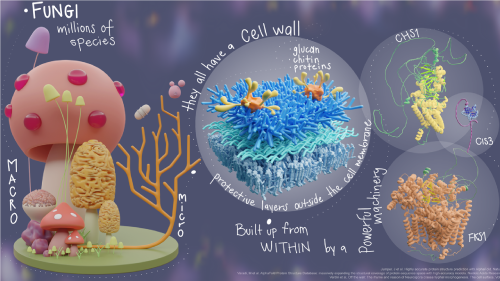

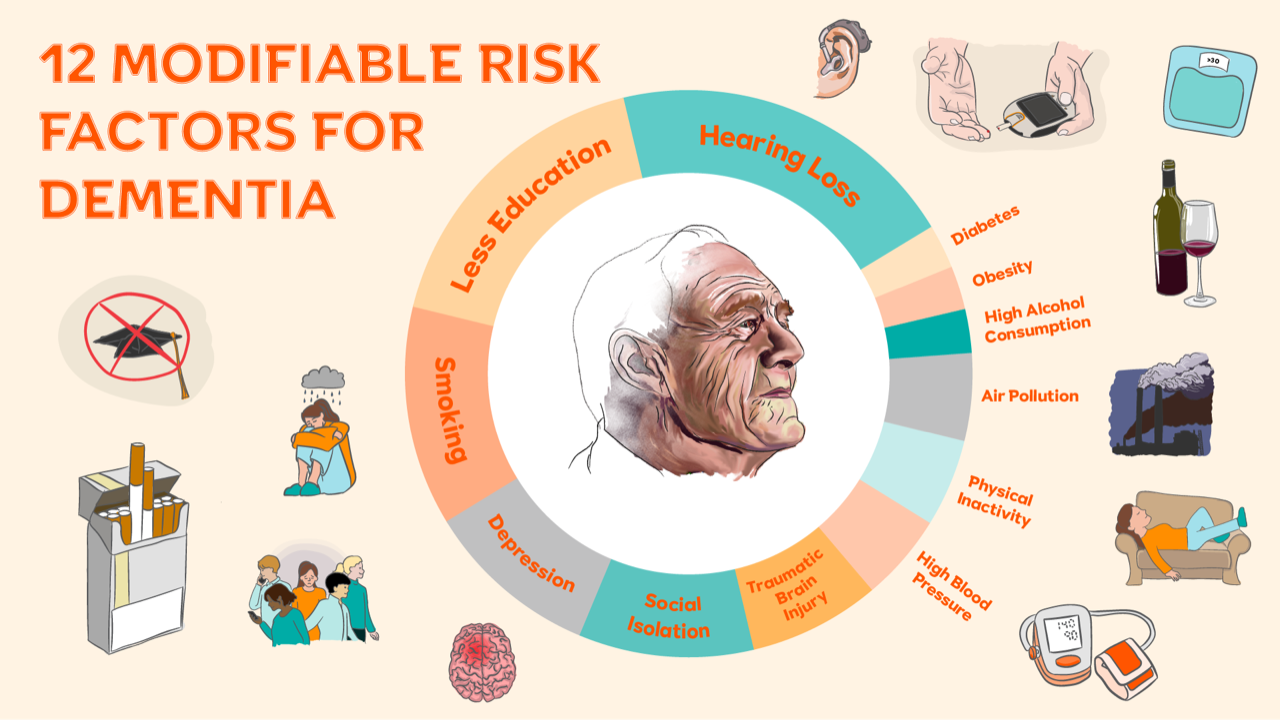

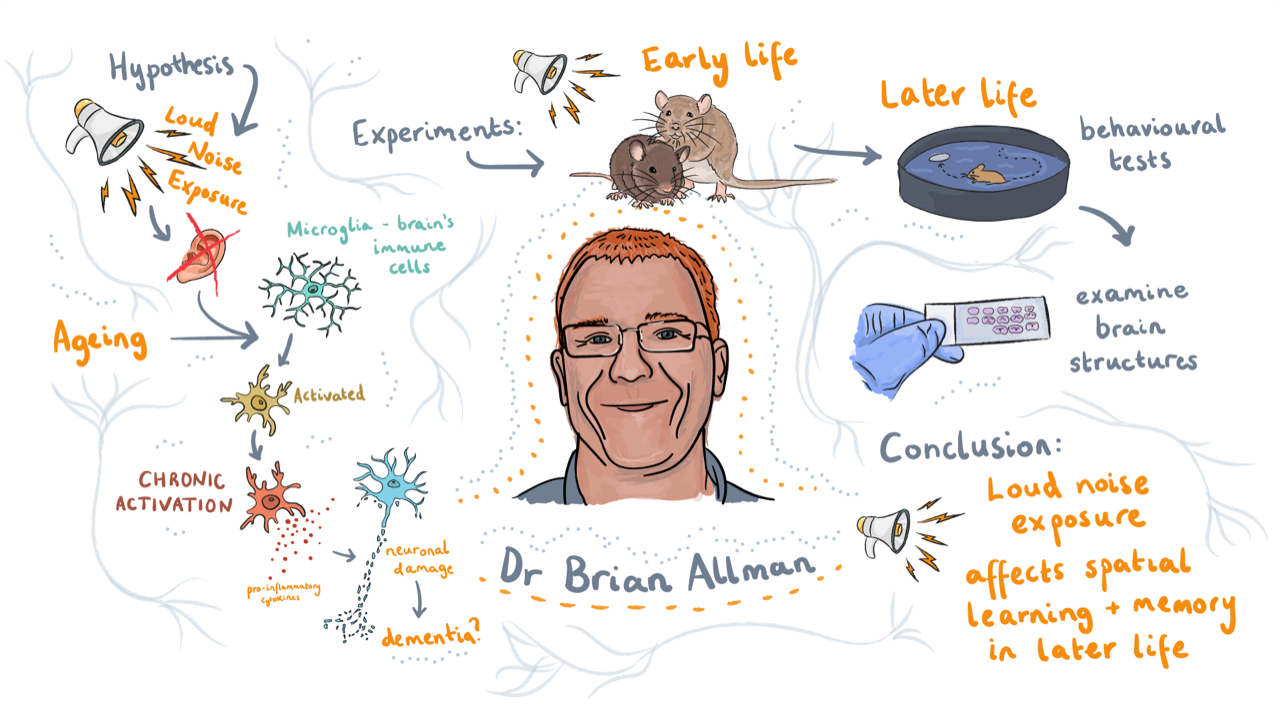

My internship ended up being about translating research on dementia prevention into infographics that could be understood by a layperson. I wanted to do this in a more creative way. ARUK was very encouraging, and I was able to get a tablet to do digital illustration and attend online courses for Adobe Illustrator. The resource that I contributed to for ARUK is called the Impact Hub, which is used by the Science communication team and other teams in the charity to communicate the impact of the research funded by the charity. The infographics I created have to clearly communicate the science in a way that can be understood by anybody. That internship was where I started to meld science and art together.

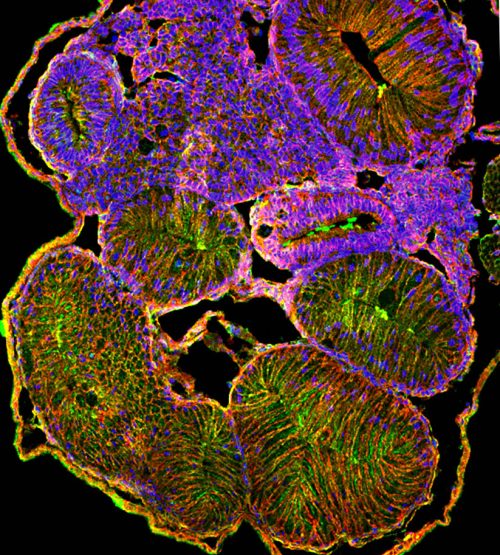

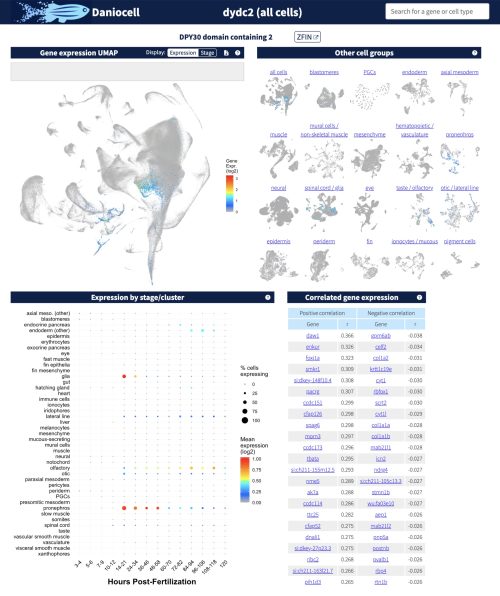

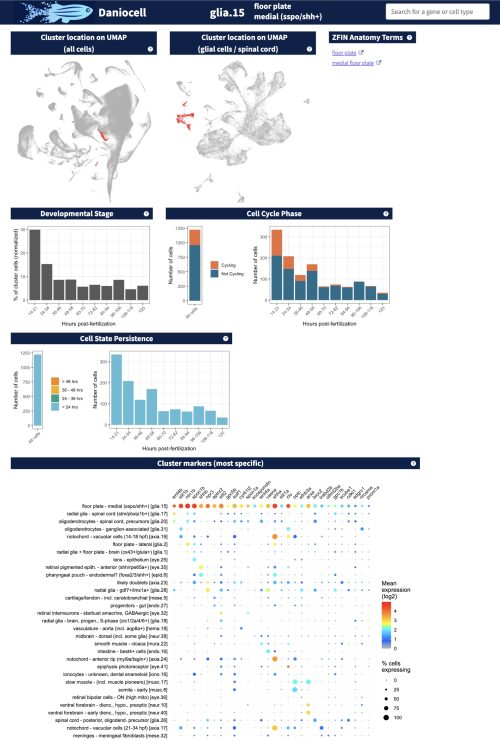

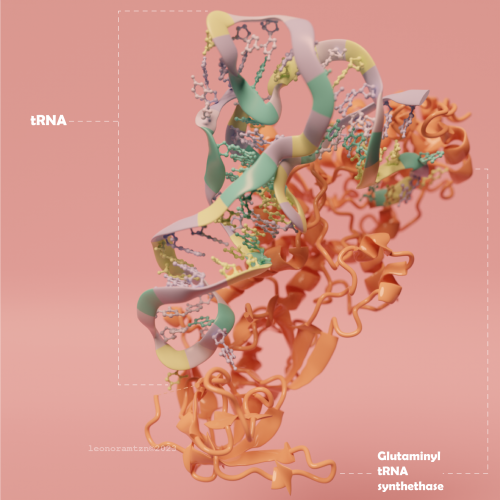

Examples of illustrations Alex did during her internship at Alzheimer’s Research UK (click to enlarge image)

Apart from scientific illustration, have you done much science communication and public outreach?

Before I started my PhD, I worked as a research assistant at the Wellcome Sanger Institute. During the COVID lockdown, I had significantly less lab work to do. I started writing a blog together with a colleague, which was quite fun to do. I also completely revamped my department’s website because it was totally out of date and very boring to look at. I’d like to think I improved it! I’ve also taken part in several outreach activities for children, such as the Big Bang Fair at Birmingham NEC, and the Cambridge Festival last year.

What is your scientific background and what is your current research focus?

I did my undergrad in biomedical sciences in York. I was initially interested in human biology and disease. But it started to change over time as I did my degree. The programme was very open, so I was able to pick a lot of different modules. It was around second or third year when I started to show an interest in developmental biology, which probably had a lot to do with my lecturers. They were very passionate about their subject, and they transferred that passion to me.

In my final year, I did a project with Xenopus embryos, which I really enjoyed. When I finished at York, I thought the one experience that I lacked was with cell culture. I started looking for jobs where I could gain those skills, and ended up joining a core facility at the Sanger Institute where I primarily did stem cell differentiation projects. I learned how to work with iPSCs and differentiate them into neural lineages. But I started to miss working model organisms and I started to realise that I wanted to pursue my own research, which I didn’t have much freedom to do as a research assistant. That was when I decided to take on a PhD at Ben Stevenson’s lab in Cambridge.

Now, I work with very early chick embryos, and I’m interested in the role of Hensen’s Node, the so-called organiser in the chick embryo, during neural development. The node is thought to be responsible for releasing signals that pattern the neural territory. If you cut the node out of the embryo it will completely regenerate itself and the embryo carries on developing. I’m studying this regenerative process and what the triggers for tissue re-specification might be and whether this has knock on effect on the development of the embryo.

You mentioned you plan to create illustrated content for the Node. Can you elaborate on your ideas?

I’d like to use my illustration skills to create new kinds of content. For example, I’d like to interview developmental biologists about their career paths and create illustrated timelines of their scientific life. I think this will be really fun to create and I think people will be interested to learn about how other people in the field got to where they are today.

I’m also thinking about doing graphical research summaries about an individual or a lab’s research, similar to a paper’s graphical abstract. I’m not sure who I’m going to interview yet, but I’ll probably start with my own lab and people that I know and then branch out.

Will you also write for the Node as well?

I’d like to gain skills in writing as well. One of the things I want to improve is how to adapt the way I write for different audiences, which I think is a really important skill as a scientist. I’d like to make content that blends both text writing and illustration.

Apart from gaining a bit more writing experience, what else do you hope to gain from being a correspondent?

I’d like to meet other people who have similar interests. I’m thinking about a potential career path into science communication after I finish my PhD. I’d like to get to know people and network and find out more about careers in this area.

Finally, what do you like to do in your spare time?

At the end of my undergraduate degree, I loved cooking and baking so much that I convinced myself that I didn’t want to do science anymore and that I actually wanted to be a recipe developer. I felt very conflicted about this because I just spent four years of my life working towards a career in science. I ended up going to my first job in science anyway at the Sanger Institute. I’m glad I did because it did revive my interest in science.

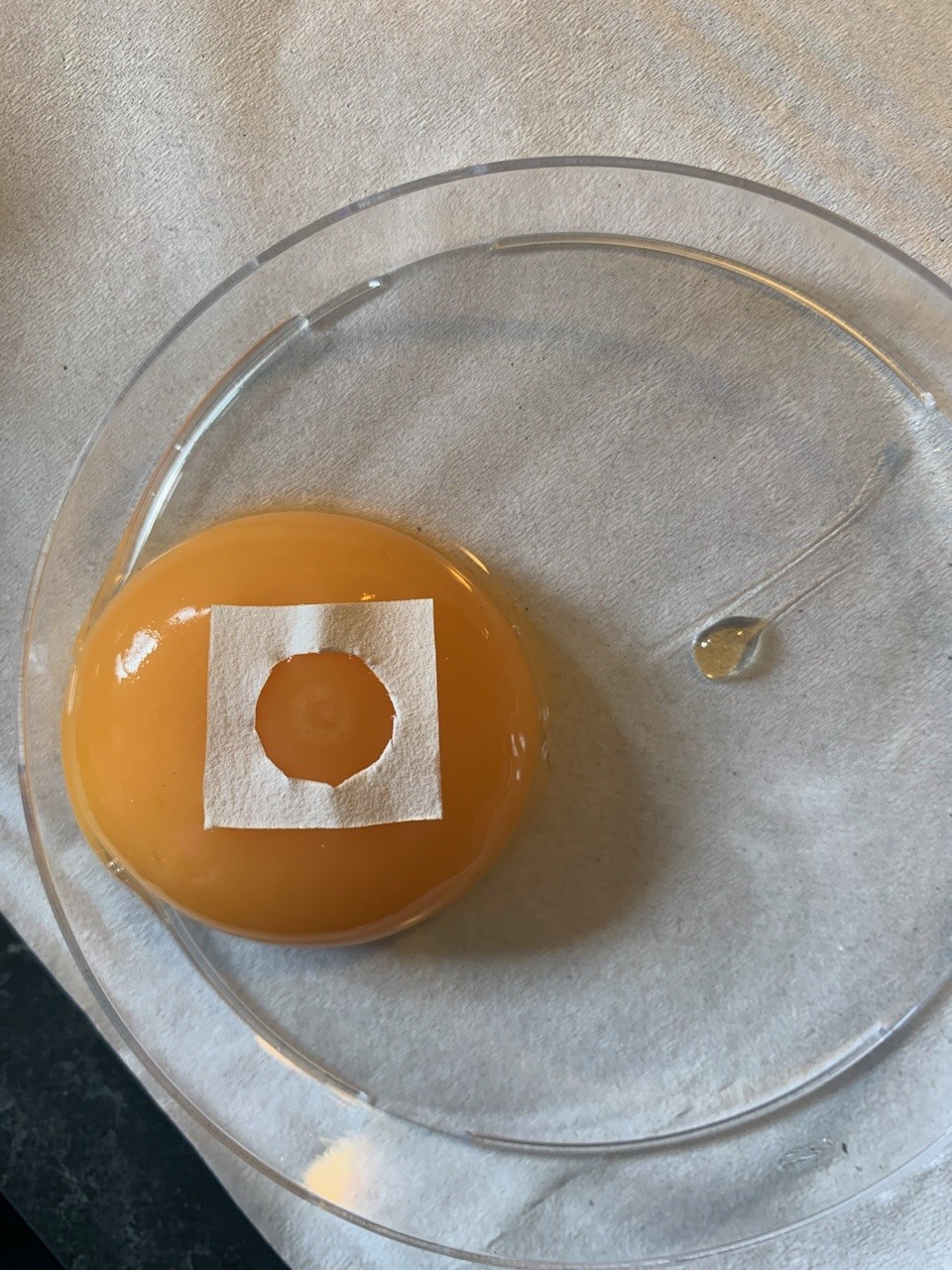

I still do a lot of baking in my spare time and my lab is more than happy to eat all of my creations. Some of my favourite bakes have been embryo themed. I’ve made some cupcakes for a friend’s viva with the stages of zebrafish development. Another friend is a fellow chick embryologist. When she finished her viva, I made some early chick culture cupcakes that were really realistic. So realistic that maybe they were slightly off putting to some people!

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(2 votes)

(2 votes)