Here are the research highlights from the current issue of Development:

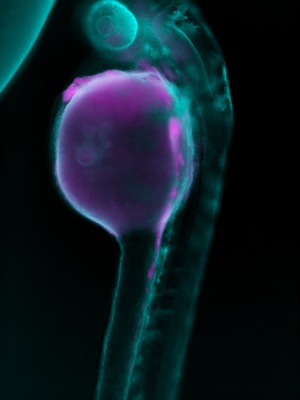

Arteriovenous-specific regulation of angiogenesis

Endothelial cells (ECs) assume arterial- or venous-specific molecular characteristics at early stages of development. These lineage-specific molecular programmes subsequently instruct the development of the distinct vascular architectures of arteries and veins. Now, on p. 1173, Jau-Nian Chen and co-workers investigate the role that these early molecular programmes play in angiogenesis. Using the zebrafish caudal vein plexus as a model for venous-specific angiogenesis, they identify a new compound, aplexone, as an inhibitor of venous, but not arterial, angiogenesis. They show that aplexone targets the HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) pathway and that injection of mevalonate, a metabolic product of HMGCR, into zebrafish embryos reverses the effect of aplexone on venous angiogenesis. They also show that the inhibitory effect of aplexone on venous angiogenesis in zebrafish and human ECs is mediated by HMGCR-regulated membrane targeting of the small GTPase RhoA through protein prenylation. These and other findings indicate that angiogenesis is differentially regulated by the HMGCR pathway in an arteriovenous-specific manner in both zebrafish and human ECs.

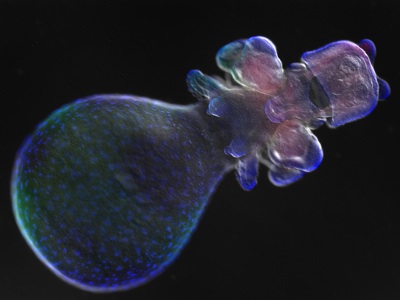

miRNA hits Barx1 in the stomach

The spatiotemporal control of gene expression is crucially important during development, and microRNAs (miRNAs; short RNA molecules that silence complementary mRNA sequences) are thought to fine-tune the expression of developmentally important genes. Here, Ramesh Shivdasani and colleagues report that specific miRNAs influence mouse stomach organogenesis by regulating the expression of the mesenchymal transcription factor Barx1 (see p. 1081). Barx1 controls stomach morphogenesis and helps to specify the stomach-specific epithelium. However, Barx1 levels in the stomach decline sharply after epithelial specification. The researchers show that depletion of the miRNA-processing enzyme Dicer in cultured stomach mesenchymal cells increases Barx1 levels and that conditional Dicer gene deletion in mice disrupts stomach development. They identify miR-7a and miR-203 as regulators of Barx1 expression and show that these miRNAs repress Barx1 expression in the developing stomach by binding to the Barx1 3′ untranslated region. Barx1 downregulation by miRNAs in the mouse embryonic stomach might thus be an example of a widely used mechanism for modulating gene expression during development.

EGF signals muscle in to maintain intestinal stem cells

In high-turnover tissues, the precise control of stem cell proliferation is essential for tissue homeostasis. In Drosophila, the integrity of the midgut epithelium is maintained by intestinal stem cells (ISCs) but what regulates the proliferation of these cells? Benoît Biteau and Heinrich Jasper now report that EGF receptor (EGFR) signalling maintains the proliferative capacity of ISCs (see p. 1045). Using clonal analysis, RNAi knockdown and other experimental approaches, the researchers show that the EGF ligand Vein is expressed in the muscle surrounding the intestinal epithelium and that Vein provides a constitutive signal that activates ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) in ISCs. Interestingly, the transcription factor FOS integrates this EGFR/ERK signal with signals mediated by the JNK (Jun N-terminal kinase) pathway in response to stress. The researchers suggest that the visceral muscle acts as a functional niche for ISCs and propose that FOS, by integrating the niche-derived permissive signal with stress-induced instructive signals, adjusts ISC proliferation to environmental conditions.

Niche-free progression of adult neural stem cells

Many tissues contain adult stem cells that could provide sources of cells for cell-based therapies. For example, adult neural stem cells (NSCs), which are found in brain regions such as the subependymal zone (SEZ), could be used to treat nervous system disorders. Little is known, however, about the intrinsic specification of adult NSCs or how dependent this specification is on the local niche. To understand the biology of NSCs better, Benedikt Berninger and co-workers have been using continuous live imaging to follow the cell divisions and lineage progression of cells isolated from the adult mouse SEZ (see p. 1057). They now report that SEZ cells cultured at low density without growth factors are primarily neurogenic, and that adult NSCs progress through stereotypic lineage trees consisting of asymmetric stem cell divisions, symmetric transit-amplifying divisions and final symmetric neurogenic divisions. The researchers conclude from these results that lineage progression from stem cell to neuron is cell-intrinsic and is independent of the local niche to a surprising degree.

Going with the flow: Pkd1l1 and Pkd2 set L-R axis

The internal organs of all vertebrates show distinct left-right (L-R) asymmetry. The earliest known event in the establishment of this asymmetry is a leftwards extracellular fluid flow at the embryonic node. This ‘nodal flow’, which is generated by the rotational movement of node cilia, activates asymmetric gene expression. But how is nodal flow detected? The two-cilia hypothesis proposes that, whereas motile cilia generate the flow, immobile node cilia detect nodal flow and respond by generating a left-sided Ca2+ signal. This signal generation is thought to be mediated by a complex consisting of the calcium channel polycystic kidney disease 2 (Pkd2) and an unknown sensor protein. In this issue, two papers further evaluate this hypothesis.

On p. 1131, Dominic Norris and colleagues identify the Pkd1-related locus Pkd1l1 as the missing Pkd2 partner and sensor protein in L-R patterning in mouse. Point mutants in either Pkd1l1 or Pkd2 fail to activate asymmetric gene expression at the node, they report, and develop similar L-R patterning defects. Cilia and node morphology and cilia motility are normal in both types of mutant, however, which suggests that Pkd1l1 and Pkd2 act downstream of nodal flow. Moreover, Pkd1l1 and Pkd2 localise to cilia and interact physically. Thus, the researchers propose, Pkd1l1 and Pkd2 form a cilia-specific stress-responsive channel in the node, a conclusion consistent with the two-cilia hypothesis.

On p. 1121, Hiroyuki Takeda and colleagues report that the medaka mutant abecobe is defective for L-R asymmetric gene expression but not for nodal flow, and identify the abecobe gene as Pkd1l1. They show that Pkd1l1 expression is confined to Kuppfer’s vesicle (KV; a medaka organ equivalent to the mouse node) and that, as in the mouse, Pkd1l1 interacts with and colocalises with Pkd2 in KV cilia. However, importantly, the researchers report that all KV cilia contain Pkd1l1 and Pkd2 and that all of the KV cilia are motile. These results necessitate reconsideration of the two-cilia model for L-R patterning and the researchers propose a new model in which cilia both generate nodal flow and interpret it through a nodal flow sensor that consists of Pkd1l1-Pkd2 complexes.

Plus…

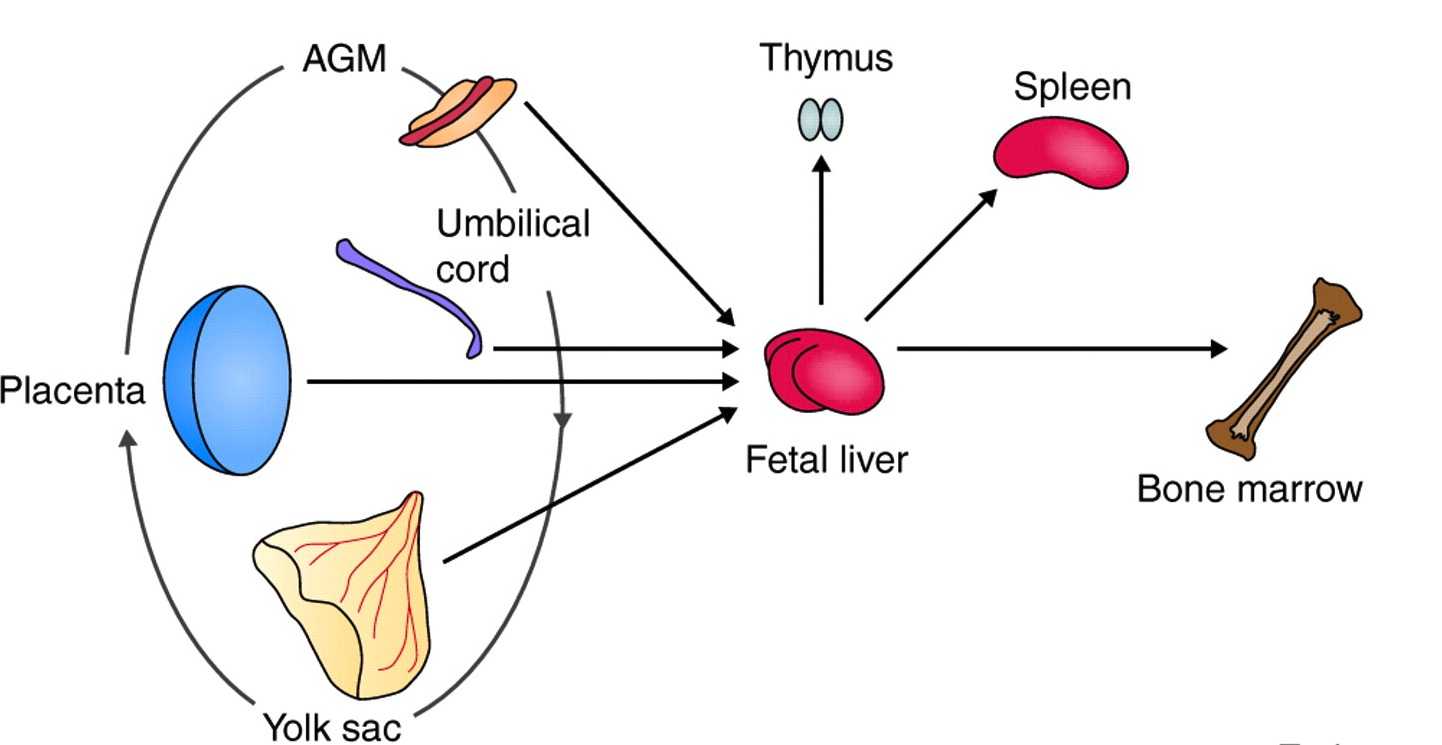

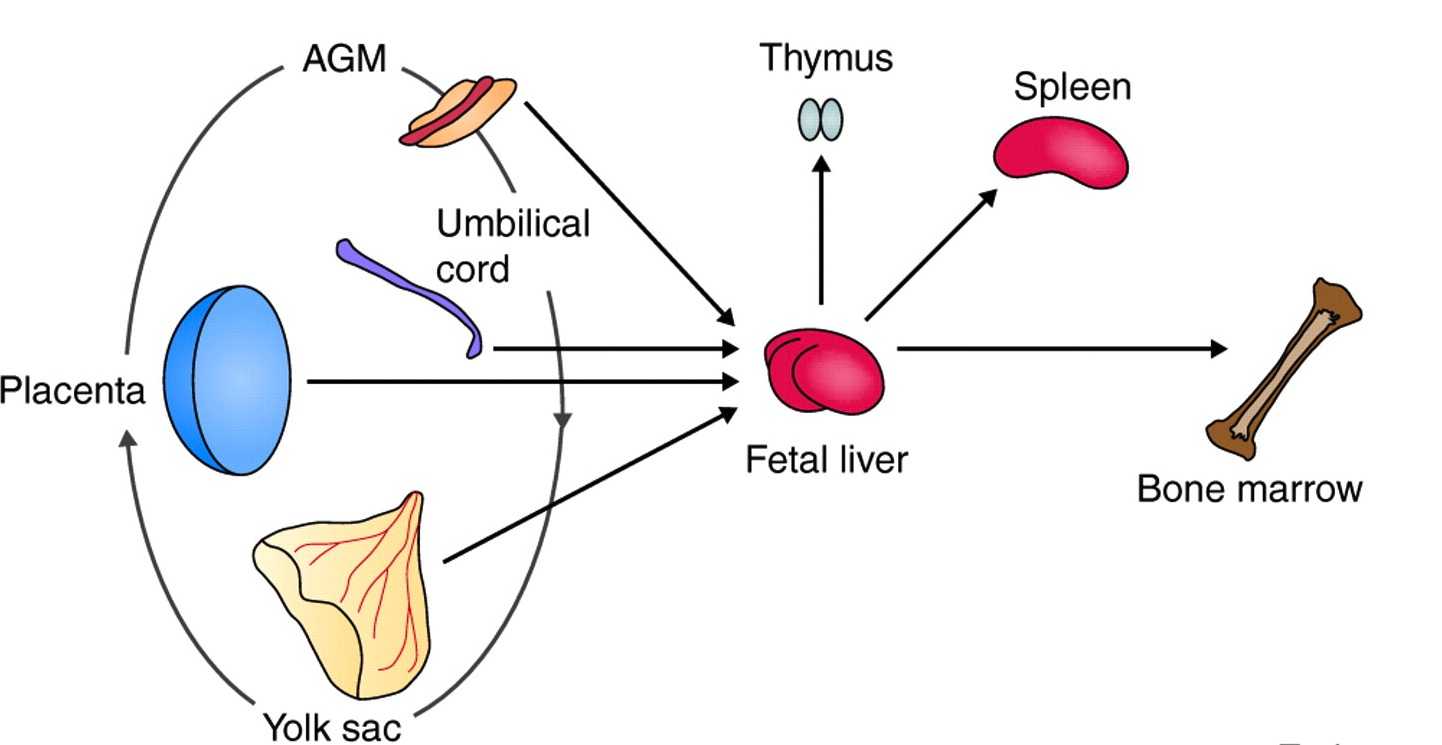

Definitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) give rise to all of the mature blood cell lineages in adults, and, as reviewed by Alexander Medvinsky and colleagues, recent advances have shed light on the embryonic origin of HSCs. See the Review Article on p. 1017

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

Loading...

Loading...

Tags: adult neural stem cells, angiogenesis, aplexone, Barx1, cilia, EGFR, HMG-CoA reductase, intestinal stem cells, left-right asymmetry, nodal flow, Pkd1l1, Pkd2, stomach development

Categories: Research

(4 votes)

(4 votes) (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)