Could we simultaneously make it easier for professional scientists to do research on tight budgets, and improve public understanding of science, by facilitating professional-amateur collaborations? Not that long ago, amateur scientists such as Darwin, Wallace, and Mendel laid the foundations of modern biology.  Today, a few button clicks gives access to vast troves of knowledge, and a few dollars buys technologies that even well-funded labs could not get a few decades ago. So, it should be much easier for amateurs and hobbyists to do scientific research now than it was in Darwin’s era. The IGoR wiki aims to pool the talents of professional, amateur, and novice scientists.

Today, a few button clicks gives access to vast troves of knowledge, and a few dollars buys technologies that even well-funded labs could not get a few decades ago. So, it should be much easier for amateurs and hobbyists to do scientific research now than it was in Darwin’s era. The IGoR wiki aims to pool the talents of professional, amateur, and novice scientists.

But why should professional scientists care? One reason is that doing research often requires far more skills than one person can truly master, and many of those skills are not emphasized in academic training. For example, in my own work I’ve often needed to do a little bit of machining, electronics, photography, and programming. Of course I could have saved a lot of time if I had mastery of those skills, in addition to all the skills that are more central to my research. It would have been very convenient to have an easy way to connect with the many non-scientists and amateurs who have expertise in the skills I needed.

Being able to tap into the wider, non-professional community could allow scientists to do research faster, cheaper, and better, by gaining access to a wider range of skills. One might be able to crowd-source the design and construction of a custom device, or a new image processing algorithm. Perhaps aquarium hobbyists could help one figure out how to culture an interesting non-model organism in lab. For example, I’d love to be able to keep my favorite bryozoans growing year round without running seawater, so I could do a side project that’s been nagging at me but which I can’t devote time to. Perhaps amateur naturalists could also help find collecting sites for interesting organisms. There are endless other possibilities.

Facilitating amateur-professional interactions would also improve public understanding of science. This is especially important in areas that intersect with developmental biology; voters are routinely called upon to make decisions related to stem cells, genetics, or evolution. The premise of every graduate school is that the best way to learn how science works is to do it, yet there are few opportunities for adult non-scientists to experience the creative and intellectual side of research. The success of the citizen science movement shows that many people are interested in participating in science. However, most citizen science projects are designed to get a large number of volunteers to do a defined task, rather than to help non-scientists plan research and interpret results. This leaves a big gulf between non-scientists and professionals.

Facilitating amateur-professional interactions would also improve public understanding of science. This is especially important in areas that intersect with developmental biology; voters are routinely called upon to make decisions related to stem cells, genetics, or evolution. The premise of every graduate school is that the best way to learn how science works is to do it, yet there are few opportunities for adult non-scientists to experience the creative and intellectual side of research. The success of the citizen science movement shows that many people are interested in participating in science. However, most citizen science projects are designed to get a large number of volunteers to do a defined task, rather than to help non-scientists plan research and interpret results. This leaves a big gulf between non-scientists and professionals.

We could help to solve both problems at once by creating mechanisms to make it easier for experienced scientists to tap into the skills and talents of amateurs and hobbyists, and for novices to tap into the knowledge and advice of experienced researchers. By doing both at once, one could build a broad community representing diverse skills, resources, and experience levels.

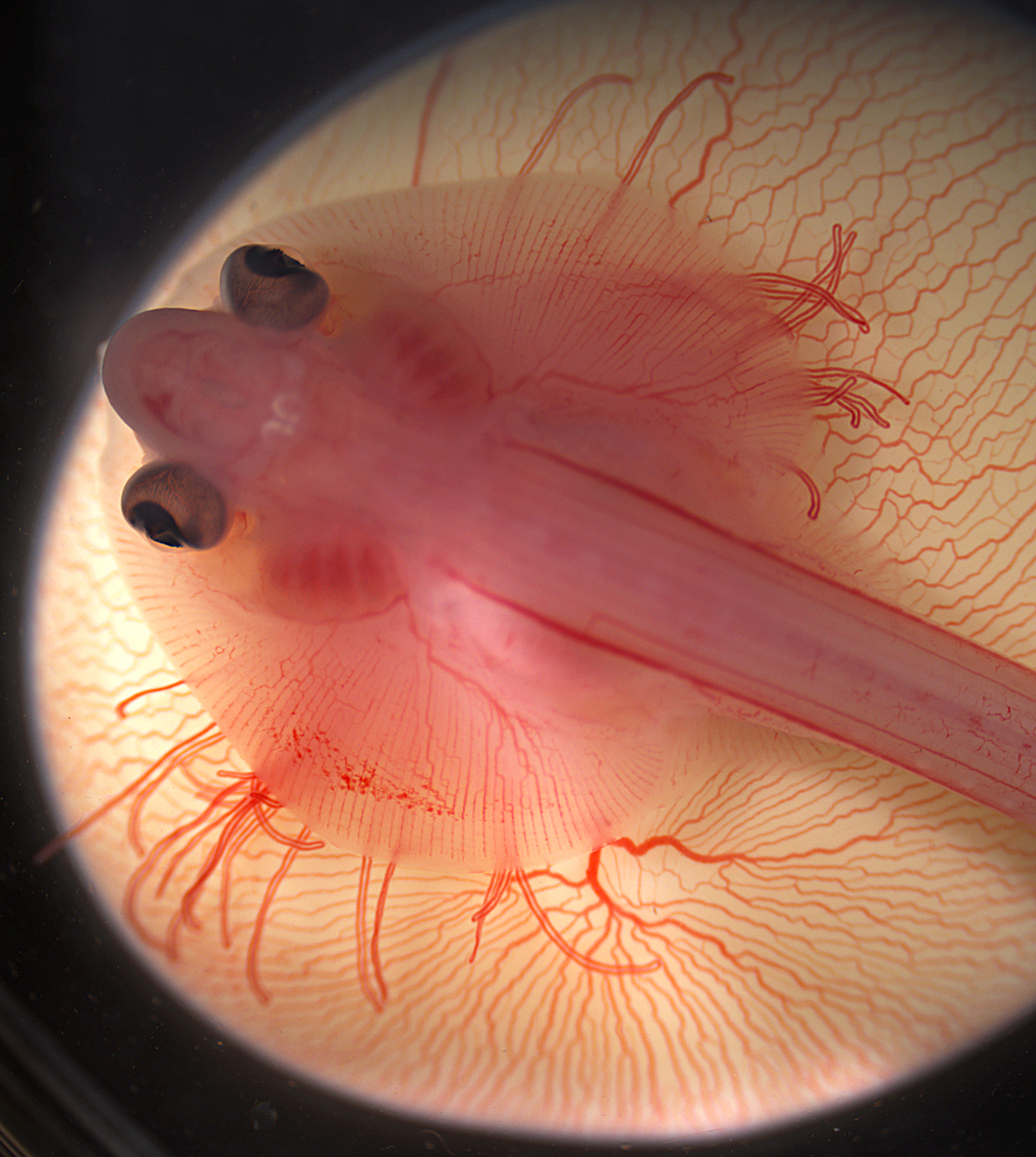

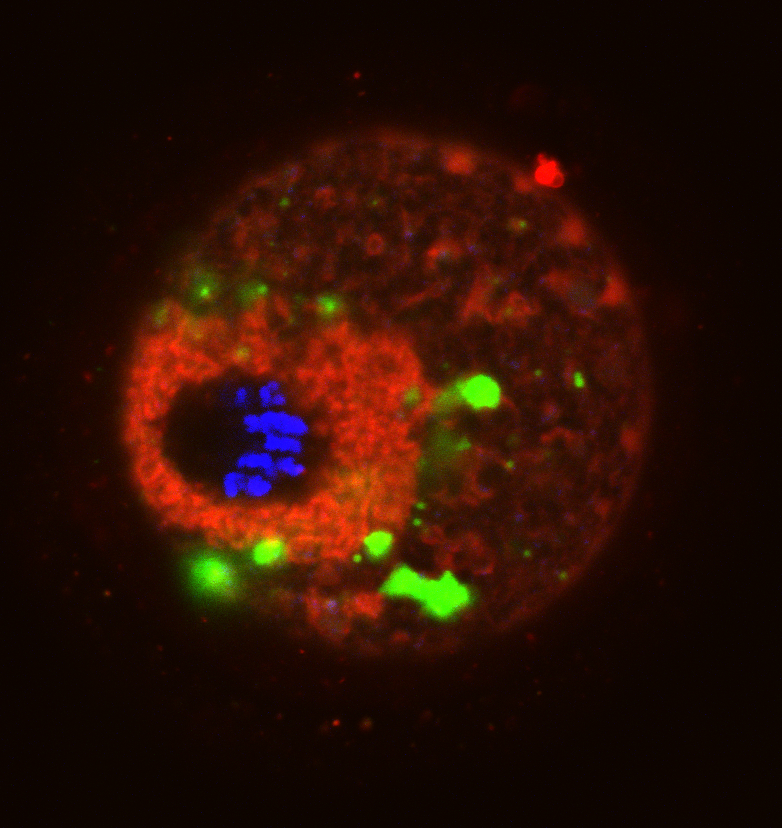

Developmental biology is ripe for this. Although a lot of developmental biology depends on expensive reagents and high-tech equipment, plenty of high-value, low-tech research remains to be done. Two of my all-time favorite papers (1, 2) used nothing more than glass needles and intelligence to identify, and partially solve, a paradox of ctenophore development: when an embryo is split in two, each half develops into half an embryo; yet the adults can regenerate an entire half of their body. The authors documented ontogenetic transitions in these phenomena, and then deciphered the roles of specific cell lineages in patterning and regeneration. In my own work, I’ve found that the most useful biomechanical techniques for working with embryos are things like micropipette aspiration, which would be easily accessible to amateur microscopists (it was developed in the 1950’s (3)). There are myriad questions in developmental biology that could be investigated with low-budget techniques.

Developmental biology is ripe for this. Although a lot of developmental biology depends on expensive reagents and high-tech equipment, plenty of high-value, low-tech research remains to be done. Two of my all-time favorite papers (1, 2) used nothing more than glass needles and intelligence to identify, and partially solve, a paradox of ctenophore development: when an embryo is split in two, each half develops into half an embryo; yet the adults can regenerate an entire half of their body. The authors documented ontogenetic transitions in these phenomena, and then deciphered the roles of specific cell lineages in patterning and regeneration. In my own work, I’ve found that the most useful biomechanical techniques for working with embryos are things like micropipette aspiration, which would be easily accessible to amateur microscopists (it was developed in the 1950’s (3)). There are myriad questions in developmental biology that could be investigated with low-budget techniques.

Are there many interested amateurs and non-scientists who might want to do real research? Yes! There is a growing number of community labs (generally focused on synthetic biology) in bigger cities. There are other online or offline communities of enthusiasts of various organisms. One of my favorite examples is a mushrooming club I joined in Pittsburgh, because there were hobbyists who had an amazing knowledge of mycology. Another of my favorite examples is Slimoco, an online community of slime mold enthusiasts: artists, engineers, hobbyists, etc. Yes, there are plenty of people with kooky ideas; but if the best way to learn how science works is by doing it, then creating mechanisms for participation in the creative and intellectual life of science should help more people become better scientists.

I’m trying to implement one idea for building an online community for research and outreach (IGoR), and I’d greatly appreciate your input on it. Setting it up as a wiki should help people break out of their existing social or professional networks, and it should help one discover unexpected forms of solutions, or problems one hadn’t considered. It is open to experienced scientists who want to tap into the talents of non-scientists and amateurs, but it’s also open to novices who want to try their hand at doing their own research with community feedback. Being equally open to professionals, amateurs, and novices should help build a diverse enough pool of skills, knowledge, and resources to solve many kinds of problems.

If you are interested in the idea, please take a look. Quick and easy things, like posting comments and rating pages on the IGoR site, will help the wiki take life and become a valuable resource for scientists at all experience levels.

1. Henry JQ, Martindale MQ. 2000. Regulation and regeneration in the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. Developmental biology.227(2):720-33. DOI:10.1006/dbio.2000.9903. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11071786

2. Martindale MQ. 1986. The ontogeny and maintenance of adult symmetry properties in the ctenophore, Mnemiopsis mccradyi. Developmental biology.118(2):556-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2878844

3. Mitchison JM, Swann MM. 1954. The Mechanical Properties of the Cell Surface: I. The Cell Elastimeter. J Exp Biol.31(3):443-60. http://jeb.biologists.org

(7 votes)

(7 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

(2 votes)

(2 votes)

Dmrt1 and its related genes play a key role in sex determination in a broad range of metazoan species. However, Dmrt1 has become dispensable for testis determination in mammals, and this function is instead carried out by Sry, which is a newly evolved gene found on the Y chromosome. Now, Peter Koopman and colleagues show that, even though its function is not normally required, Dmrt1 is able to drive female-to-male sex reversal in mice (p.

Dmrt1 and its related genes play a key role in sex determination in a broad range of metazoan species. However, Dmrt1 has become dispensable for testis determination in mammals, and this function is instead carried out by Sry, which is a newly evolved gene found on the Y chromosome. Now, Peter Koopman and colleagues show that, even though its function is not normally required, Dmrt1 is able to drive female-to-male sex reversal in mice (p.  In plants, stem cell proliferation is negatively regulated by the receptor kinase CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and its peptide ligand CLAVATA3 (CLV3). Previous studies have suggested that CLV1 acts redundantly with other receptor kinases, such as BAM1, 2 and 3, but the molecular mechanisms underpinning this redundancy have been unclear. Now, Elliot Meyerowitz and co-workers interrogate the role of CLV1-CLV3 signalling in the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem (p.

In plants, stem cell proliferation is negatively regulated by the receptor kinase CLAVATA1 (CLV1) and its peptide ligand CLAVATA3 (CLV3). Previous studies have suggested that CLV1 acts redundantly with other receptor kinases, such as BAM1, 2 and 3, but the molecular mechanisms underpinning this redundancy have been unclear. Now, Elliot Meyerowitz and co-workers interrogate the role of CLV1-CLV3 signalling in the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem (p.  Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) give rise to all cells of the adult blood system, and understanding how these cells first arise during embryogenesis is important for developing regenerative medicine-based strategies for producing HSCs in vitro. Here, David Traver and colleagues demonstrate that Gata2b acts as an early regulator of zebrafish hematopoietic precursors (p.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) give rise to all cells of the adult blood system, and understanding how these cells first arise during embryogenesis is important for developing regenerative medicine-based strategies for producing HSCs in vitro. Here, David Traver and colleagues demonstrate that Gata2b acts as an early regulator of zebrafish hematopoietic precursors (p. Adherens junctions (AJs), which are specialised E-cadherin-based cell contacts, are continuously remodelled during tissue morphogenesis, as cells change shape and position. The accumulation of Bazooka (Baz), the Drosophila PAR3 homologue, is thought to specify where new E-cadherin complexes are deposited during AJ remodelling, but what regulates Baz localisation? Here, Alexandre Djiane and colleagues show that the scaffold protein Magi regulates Baz localization and hence AJ remodelling inDrosophila eye epithelial cells (p.

Adherens junctions (AJs), which are specialised E-cadherin-based cell contacts, are continuously remodelled during tissue morphogenesis, as cells change shape and position. The accumulation of Bazooka (Baz), the Drosophila PAR3 homologue, is thought to specify where new E-cadherin complexes are deposited during AJ remodelling, but what regulates Baz localisation? Here, Alexandre Djiane and colleagues show that the scaffold protein Magi regulates Baz localization and hence AJ remodelling inDrosophila eye epithelial cells (p.  Skeletal stem cells (SSCs) reside in the postnatal bone marrow and give rise to cartilage, bone, hematopoiesis-supportive stroma and marrow adipocytes. Here, Paolo Bianco and Pamela Robey discuss the biology of SSCs in the context of the development and postnatal physiology of skeletal lineages, to which their use in medicine must remain anchored. See the Development at a Glance poster article on p.

Skeletal stem cells (SSCs) reside in the postnatal bone marrow and give rise to cartilage, bone, hematopoiesis-supportive stroma and marrow adipocytes. Here, Paolo Bianco and Pamela Robey discuss the biology of SSCs in the context of the development and postnatal physiology of skeletal lineages, to which their use in medicine must remain anchored. See the Development at a Glance poster article on p.  The mammary gland provides an excellent model for studying ‘stem/progenitor’ cells, which – in this context – allow for the repeated expansion and renewal of the gland during adult life. Here, Mina Bissell and colleagues discuss the various cell types that constitute the mammary gland, highlighting how they arise and differentiate, and how the microenvironment influences their development. See the Review on p.

The mammary gland provides an excellent model for studying ‘stem/progenitor’ cells, which – in this context – allow for the repeated expansion and renewal of the gland during adult life. Here, Mina Bissell and colleagues discuss the various cell types that constitute the mammary gland, highlighting how they arise and differentiate, and how the microenvironment influences their development. See the Review on p.  (No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet) Today, a few button clicks gives access to vast troves of knowledge, and a few dollars buys technologies that even well-funded labs could not get a few decades ago. So, it should be much easier for amateurs and hobbyists to do scientific research now than it was in Darwin’s era. The

Today, a few button clicks gives access to vast troves of knowledge, and a few dollars buys technologies that even well-funded labs could not get a few decades ago. So, it should be much easier for amateurs and hobbyists to do scientific research now than it was in Darwin’s era. The  Facilitating amateur-professional interactions would also improve public understanding of science. This is especially important in areas that intersect with developmental biology; voters are routinely called upon to make decisions related to stem cells, genetics, or evolution. The premise of every graduate school is that the best way to learn how science works is to do it, yet there are few opportunities for adult non-scientists to experience the creative and intellectual side of research. The success of the citizen science movement shows that many people are interested in participating in science. However, most citizen science projects are designed to get a large number of volunteers to do a defined task, rather than to help non-scientists plan research and interpret results. This leaves a big gulf between non-scientists and professionals.

Facilitating amateur-professional interactions would also improve public understanding of science. This is especially important in areas that intersect with developmental biology; voters are routinely called upon to make decisions related to stem cells, genetics, or evolution. The premise of every graduate school is that the best way to learn how science works is to do it, yet there are few opportunities for adult non-scientists to experience the creative and intellectual side of research. The success of the citizen science movement shows that many people are interested in participating in science. However, most citizen science projects are designed to get a large number of volunteers to do a defined task, rather than to help non-scientists plan research and interpret results. This leaves a big gulf between non-scientists and professionals. Developmental biology is ripe for this. Although a lot of developmental biology depends on expensive reagents and high-tech equipment, plenty of high-value, low-tech research remains to be done. Two of my all-time favorite papers (1, 2) used nothing more than glass needles and intelligence to identify, and partially solve, a paradox of ctenophore development: when an embryo is split in two, each half develops into half an embryo; yet the adults can regenerate an entire half of their body. The authors documented ontogenetic transitions in these phenomena, and then deciphered the roles of specific cell lineages in patterning and regeneration. In my own work, I’ve found that the most useful biomechanical techniques for working with embryos are things like micropipette aspiration, which would be easily accessible to amateur microscopists (it was developed in the 1950’s (3)). There are myriad questions in developmental biology that could be investigated with low-budget techniques.

Developmental biology is ripe for this. Although a lot of developmental biology depends on expensive reagents and high-tech equipment, plenty of high-value, low-tech research remains to be done. Two of my all-time favorite papers (1, 2) used nothing more than glass needles and intelligence to identify, and partially solve, a paradox of ctenophore development: when an embryo is split in two, each half develops into half an embryo; yet the adults can regenerate an entire half of their body. The authors documented ontogenetic transitions in these phenomena, and then deciphered the roles of specific cell lineages in patterning and regeneration. In my own work, I’ve found that the most useful biomechanical techniques for working with embryos are things like micropipette aspiration, which would be easily accessible to amateur microscopists (it was developed in the 1950’s (3)). There are myriad questions in developmental biology that could be investigated with low-budget techniques.