My name is Nikos. I just finished my PhD in the lab of Michalis Averof , starting my thesis at IMBB, in Crete and completing it at IGFL, in Lyon. My project aimed to introduce a new arthropod model to regeneration studies. Its main part was published recently (http://www.sciencemag.org/content/343/6172/788.abstract). In this Node post, I would like to present this new animal model and to summarize our findings in a more relaxed manner. I tend to read Node posts during experimental incubations; I hope I will be able to transmit my enthusiasm within this small break.

Why Parhyale?

Parhyale hawaiensis (closely related to the common beach hoppers – Figure 1) has emerged lately as a promising model organism for comparative developmental studies. A wonderful post describing how life proceeds in a Parhyale lab was posted recently in The Node by Erin Jarvis. The concerted effort of a few labs across the world has lead to the development of several genetic tools in Parhyale. We are now able to create transgenic animals either by random insertion of a transgene or by site-specific integration, to overexpress or downregulate our genes of interest, to perform mosaic analysis, gene-trapping etc. Moreover, transcriptomic and genomic data are accessible in the form of EST, BAC and RNA-seq datasets for embryogenesis.

What really fascinated us, though, and triggered me to commence this study is the ability of crustaceans (including Parhyale) to regenerate. Parhyale regenerates all of its appendages – antennae, thoracic and abdominal appendages – within about a week of amputation. It is necessary to mention that Parhyale, like all crustaceans, go through successive molts where they shed their exoskeleton and replace it by a new one during their entire lifetime. The regenerated appendage, although it is formed within the old exoskeleton, is only revealed after molting. Using genetic markers expressed in different cell types, I showed that all major tissues are restored after regeneration. Nerves and epidermis regenerate first, muscles regenerate later.

Figure 1: Parhyale hawaiensis possesses a number of diverse and specialized appendages, including antennae, feeding appendages, locomotory appendages, uropods and pleopods, all of which can regenerate upon amputation.

Figure 1: Parhyale hawaiensis possesses a number of diverse and specialized appendages, including antennae, feeding appendages, locomotory appendages, uropods and pleopods, all of which can regenerate upon amputation.

Why regeneration?

Regeneration is the process through which animals restore a body part after injury. Regeneration has incited human curiosity for a long time, e.g. there are well-known accounts of regeneration in Greek mythology; the Lernaean Hydra regenerated its heads, Prometheus regenerated his liver. Comprehending how different animals regenerate their body parts has been hindered by the fact that established animal models, like flies, mice and worms, have poor regenerative abilities.

Studying regeneration can facilitate our approach towards several stimulating questions. Several questions came to my mind at the beginning of my thesis. Why do some animals regenerate efficiently, whereas others do not? Do the animals that regenerate use common cellular and/or molecular mechanisms? Answers to these questions can help us construct the evolutionary history of regenerative capacity. Does regenerative capacity of different animals share a common origin or was it acquired during the evolution of different animal lineages?

Regenerative studies can also contribute to the rapidly evolving field of regenerative medicine. Researchers have been aiming (and succeeding) to de-differentiate, trans-differentiate and induce pluripotency in many different cell types. Studying natural phenomena of regeneration, where nature challenges the differentiated state of different cell types and manages to generate functional tissues, can provide invaluable insights for reprogramming studies.

Lineage restriction of regeneration progenitors

Our first question was whether regeneration progenitors in Parhyale are totipotent or lineally restricted. In different animals, varying degrees of progenitor commitment have been described. Planarians employ totipotent cells, termed neoblasts, to regenerate every part of the body that is missing1. Vertebrates, on the other hand, utilize progenitors that retain their commitment to a specific lineage2,3. In specific circumstances, transdifferentiation (transformation of a differentiated cell type into a different differentiated cell type) has been reported to occur during regeneration, e.g. during lens regeneration in newts4.

I created mosaic animals, in which specific cell lineages were marked with a transgene carrying EGFP under the control of a Parhyale heat-shock promoter. I then assessed the contribution of these marked cell lineages to regenerated tissues. My mosaic animals carried the marker transgene in cell lineages that contribute to different portions of the ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm or germline. After regeneration, I recorded which of the newly regenerated tissues expressed EGFP, which would indicate that it derived from the marked lineage.

I discovered that the regeneration progenitors in Parhyale have a regenerative potential that is restricted with respect to germ layers and, moreover, that they reside close to the regenerating tissue. For example, cell lineages that during embryonic development contribute to ectoderm on the left side of the body regenerate the epidermis and nerves on the limbs of the left side, cell lineages that contribute to mesoderm on the right side of the body could regenerate the muscles of the right side, and so on.

These results exclude the participation of totipotent progenitor cell in Parhyale limb regeneration, as is the case in planarians, and restrict possible transdifferentiation events to transdifferentiation between cells of the same germ layer; if transdifferentiation occurs, it does not cross the borders between ectoderm and mesoderm. My results indicate that, in terms of precursor plasticity, Parhyale resembles vertebrates in using lineally-restricted progenitors to create the new tissues.

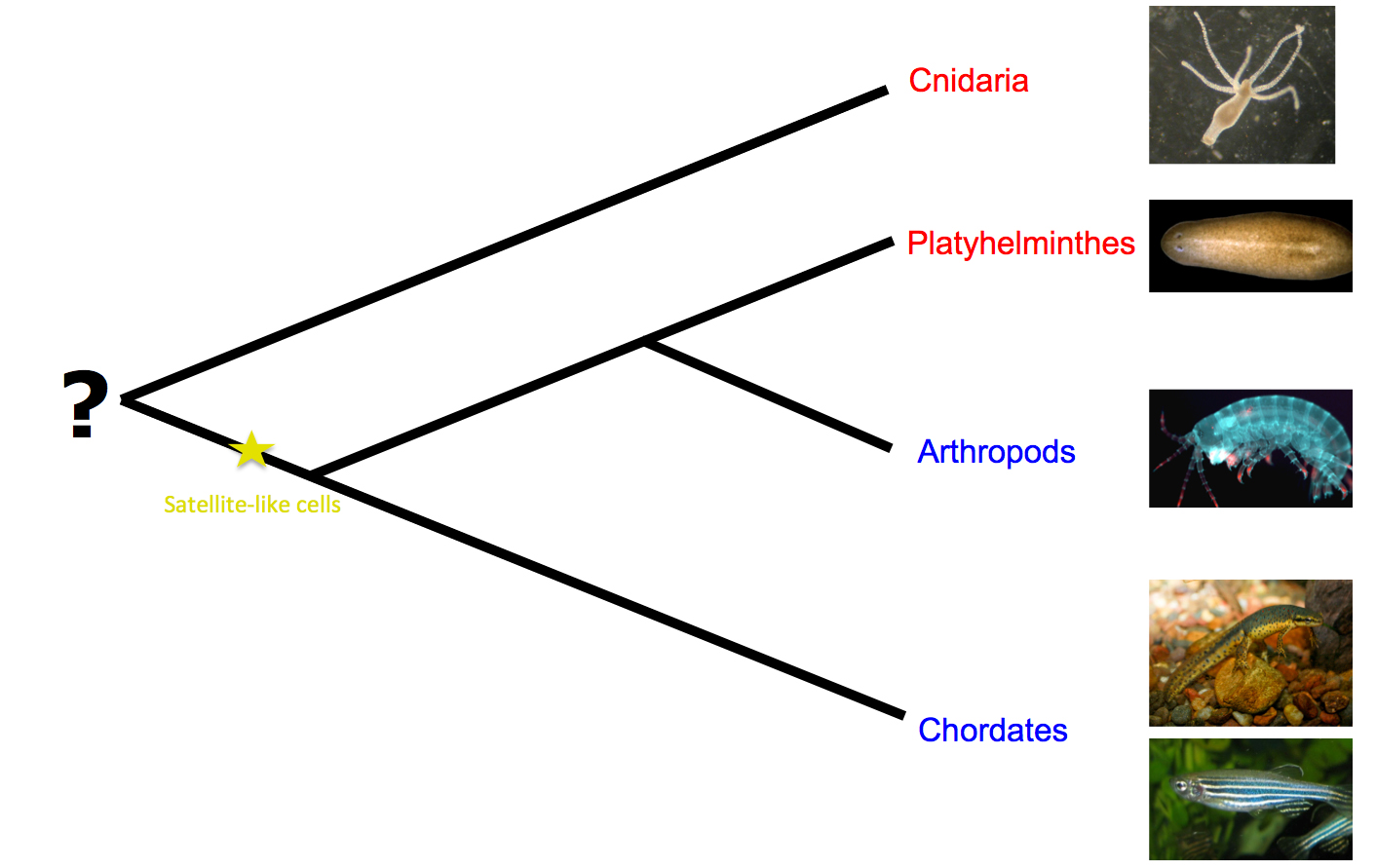

The fact that totipotent cells have not been identified in vertebrates and crustaceans supports the argument that neoblasts are an evolutionary novelty of Platyhelminthes. On the other hand, totipotent stem cells that participate in regeneration have also been observed in some species of cnidarians5. So, the question remains: if the common ancestor of Metazoa could regenerate, would this be through totipotent or lineally restricted progenitors? It can only be answered by wider comparisons among the animals that have the capacity to regenerate.

Satellite-like cells regenerate Parhyale muscle

In the second part of my project, I decided to look in greater detail within the ectodermal and mesodermal cell lineages that contribute to the regenerated tissues. I was lucky to have a transgenic reporter in the lab, PhMS-DsRed, that expresses DsRed in muscles6, as well as two cross-reactive antibodies that recognize members of the Pax3/7 family of transcription factors7. Using these tools, I discovered that Parhyale possess a mesodermal cell type that expresses Pax3/7 and is closely associated with muscle fibers. These cells are reminiscent of vertebrate muscle satellite cells; we therefore named them satellite-like cells. Vertebrate muscle satellite cells participate in muscle repair, growth and regeneration8.

I noticed that the PhMS regulatory element is active in the satellite-like cells. Using transgenic animals that carried a PhMS-EGFP transgene (expressing EGFP in muscles and in satellite-like cells), I isolated satellite-like cells from dissociated limbs and transplanted them in wild type recipients with amputated appendages. I screened these animals after regeneration and observed that a small number of muscle fibers in the newly regenerated limbs expressed EGFP, which suggests that they were derived (at least in part) from the transplanted satellite-like cells. These results prove that satellite-like cells can participate in muscle regeneration in Parhyale. We cannot exclude that other cells could also act as muscle progenitors in regeneration. Cells that derive from dedifferentiated muscle fibers have been shown to drive muscle regeneration in newts. Interestingly, axolotls (another salamander species) achieve muscle regeneration by activation of satellite cells and not through muscle dedifferentiation9. It would be interesting to find out if dedifferentiated muscle cells also participate in Parhyale muscle regeneration.

Before this study, satellite cells had only been identified in chordates. Assuming satellite-like cell homology to vertebrate satellite cells, their discovery in arthropods advocates the presence of satellite cells in the common ancestor of protostomes and deuterostomes. Moreover, satellite cell participation in muscle repair and/or regeneration in vertebrates and in Parhyale urges us to think about the evolutionary origin of these cells. The common ancestors of protostomes and deuterostomes may have been capable of repairing their muscles with the involvement of satellite cells. Alternatively, they may have carried satellite cells that were not engaged in muscle repair, but were perhaps pre-adapted to assume this role (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Regeneration models and possible emergence of satellite-like cells. Red indicates the taxa where the participation of totipotent cells in regeneration has been reported, whereas blue designates the taxa where regeneration has been shown to proceed solely through lineage-restricted progenitors. (Images taken from Wikipedia.)

So…

Where do we stand in the quest of understanding the evolution of regenerative capacity? Is regeneration an ancient trait that was lost in some lineages or has it evolved independently many times? Only informed guesses can be made.

Regenerative capacity may have evolved independently in different lineages. This could be easier to achieve than it is usually thought. The information for creating body parts is already encoded in the genome and has already been employed during embryonic development. Evolving the capacity to regenerate might just involve finding a way to redeploy this information.

Alternatively, regenerative capacity may be an ancient trait that was lost in certain lineages. In some animals, for example ones that are very short-lived, regeneration might not present a selective advantage. The loss of regenerative capacity could also be attributed to its incompatibility with another adaptive trait, such as fast healing via the formation of a fibrotic scar10.

References:

1. Wagner, D. E., I. E. Wang, et al. (2011). “Clonogenic neoblasts are pluripotent adult stem cells that underlie planarian regeneration.” Science 332(6031): 811-816.

2. Kragl, M., D. Knapp, et al. (2009). “Cells keep a memory of their tissue origin during axolotl limb regeneration.” Nature 460(7251): 60-65.

3. Rinkevich, Y., P. Lindau, et al. (2011). “Germ-layer and lineage-restricted stem/progenitors regenerate the mouse digit tip.” Nature 476(7361): 409-413.

4. Del Rio-Tsonis, K. and P. A. Tsonis (2003). “Eye regeneration at the molecular age.” Dev Dyn 226(2): 211-224.

5. Muller, W. A., R. Teo, et al. (2004). “Totipotent migratory stem cells in a hydroid.” Dev Biol 275(1): 215-224.

6. Pavlopoulos, A. and M. Averof (2005). “Establishing genetic transformation for comparative developmental studies in the crustacean Parhyale hawaiensis.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(22): 7888-7893.

7. Davis, G. K., J. A. D’Alessio, et al. (2005). “Pax3/7 genes reveal conservation and divergence in the arthropod segmentation hierarchy.” Dev Biol 285(1): 169-184.

8. Wang, Y. X. and M. A. Rudnicki (2012). “Satellite cells, the engines of muscle repair.” Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13(2): 127-133.

9. Sandoval-Guzman, T., H. Wang, et al. (2014). “Fundamental Differences in Dedifferentiation and Stem Cell Recruitment during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration in Two Salamander Species.” Cell Stem Cell 14(2): 174-187

10. Brockes, J. P., A. Kumar, et al. (2001). “Regeneration as an evolutionary variable.” J Anat 199(Pt 1-2): 3-11.

(4 votes)

(4 votes)

Loading...

Loading...

![]()

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(1 votes)

(1 votes)

Wnt, Fgf and retinoic acid signalling play a key role in patterning the posterior neural plate to form the midbrain, hindbrain and spinal cord. Despite intense study of Wnt signalling and neural patterning, only a few target transcription factors that mediate spinal cord development have been identified and the mechanism remains unclear. In this issue (p.

Wnt, Fgf and retinoic acid signalling play a key role in patterning the posterior neural plate to form the midbrain, hindbrain and spinal cord. Despite intense study of Wnt signalling and neural patterning, only a few target transcription factors that mediate spinal cord development have been identified and the mechanism remains unclear. In this issue (p.  The thymus is central to the adaptive immune system, but it is one of the first organs to undergo an age-related decline in function. Reduced expression of the thymic epithelial cell (TEC)-specific transcription factor FOXN1 has been associated with thymus degeneration, but whether restoration of FOXN1 expression can regenerate an aged thymus is unknown. Now, on p.

The thymus is central to the adaptive immune system, but it is one of the first organs to undergo an age-related decline in function. Reduced expression of the thymic epithelial cell (TEC)-specific transcription factor FOXN1 has been associated with thymus degeneration, but whether restoration of FOXN1 expression can regenerate an aged thymus is unknown. Now, on p.  Muscle stem cells, called satellite cells, are responsible for muscle growth and repair throughout life. Different subsets of satellite cells have varying degrees of self-renewal and differentiation potential, but how and when these different subsets arise has not been addressed in vivo. Now, on p.

Muscle stem cells, called satellite cells, are responsible for muscle growth and repair throughout life. Different subsets of satellite cells have varying degrees of self-renewal and differentiation potential, but how and when these different subsets arise has not been addressed in vivo. Now, on p.  Unlike somatic cells, the nucleus of the oocyte and very early embryo contains a morphologically distinct nucleolus called the nucleolus precursor body (NPB). Although this enigmatic structure has been shown to be essential for normal mammalian development, its precise function remains unclear. In this issue, Helena Fulka and Alena Langerova now demonstrate (p.

Unlike somatic cells, the nucleus of the oocyte and very early embryo contains a morphologically distinct nucleolus called the nucleolus precursor body (NPB). Although this enigmatic structure has been shown to be essential for normal mammalian development, its precise function remains unclear. In this issue, Helena Fulka and Alena Langerova now demonstrate (p.  The WUSCHEL (WUS) family of transcription factors is well known for its role in stem cell maintenance in seed plants. There are two paralogues of the WUS-RELATED HOMEOBOX 13 (WOX13) gene in the moss Physcomitrella patens, but their function is unknown. Now, on p.

The WUSCHEL (WUS) family of transcription factors is well known for its role in stem cell maintenance in seed plants. There are two paralogues of the WUS-RELATED HOMEOBOX 13 (WOX13) gene in the moss Physcomitrella patens, but their function is unknown. Now, on p.  Retinoic acid (RA) is essential for many developmental processes, but signalling levels must be tightly regulated since too much RA signalling can cause developmental defects. Cyp26 enzymes help to control this balance, metabolising RA and ensuring the correct specification of multiple different organs. Loss of Cyp26 activity can affect heart formation, and now (see p.

Retinoic acid (RA) is essential for many developmental processes, but signalling levels must be tightly regulated since too much RA signalling can cause developmental defects. Cyp26 enzymes help to control this balance, metabolising RA and ensuring the correct specification of multiple different organs. Loss of Cyp26 activity can affect heart formation, and now (see p.  Morphological asymmetry is a common feature of animal body plans, from shell coiling in snails to organ placement in humans. Many vertebrates use cilia for breaking symmetry during development: rotating cilia produce a leftward flow of extracellular fluids that induces asymmetric expression of the signaling protein Nodal. By contrast, Nodal asymmetry can be induced flow-independently in invertebrates. Here, Martin Blum et al ask when and why flow evolved, and propose that flow was present at the base of the deuterostomes and that it is required to maintain organ asymmetry in otherwise perfectly bilaterally symmetrical vertebrates. See the Hypothesis on p.

Morphological asymmetry is a common feature of animal body plans, from shell coiling in snails to organ placement in humans. Many vertebrates use cilia for breaking symmetry during development: rotating cilia produce a leftward flow of extracellular fluids that induces asymmetric expression of the signaling protein Nodal. By contrast, Nodal asymmetry can be induced flow-independently in invertebrates. Here, Martin Blum et al ask when and why flow evolved, and propose that flow was present at the base of the deuterostomes and that it is required to maintain organ asymmetry in otherwise perfectly bilaterally symmetrical vertebrates. See the Hypothesis on p.  Over the past 20 years, diverse roles for the Hippo pathway have emerged, the majority of which in vertebrates are determined by the transcriptional regulators TAZ and YAP. Accurate control of the levels and localization of these factors is thus essential for early developmental events, as well as for tissue homeostasis, repair and regeneration. Here, Bob Varelas provides an overview of the processes and pathways modulated by TAZ and YAP and outlines how TAZ and YAP contribute to organ homeostasis and regeneration. See the Review on p.

Over the past 20 years, diverse roles for the Hippo pathway have emerged, the majority of which in vertebrates are determined by the transcriptional regulators TAZ and YAP. Accurate control of the levels and localization of these factors is thus essential for early developmental events, as well as for tissue homeostasis, repair and regeneration. Here, Bob Varelas provides an overview of the processes and pathways modulated by TAZ and YAP and outlines how TAZ and YAP contribute to organ homeostasis and regeneration. See the Review on p.

Figure 1: Parhyale hawaiensis possesses a number of diverse and specialized appendages, including antennae, feeding appendages, locomotory appendages, uropods and pleopods, all of which can regenerate upon amputation.

Figure 1: Parhyale hawaiensis possesses a number of diverse and specialized appendages, including antennae, feeding appendages, locomotory appendages, uropods and pleopods, all of which can regenerate upon amputation.