Rethinking X-chromosome Inactivation

Posted by LucyHaizlipWilliams, on 30 April 2011

I’ve been asked to present the back-story behind our recently published manuscript in Development “Transcription precedes loss of Xist coating and depletion of H3K27me3 during X-chromosome reprogramming in the mouse inner cell mass.”

I’ve been asked to present the back-story behind our recently published manuscript in Development “Transcription precedes loss of Xist coating and depletion of H3K27me3 during X-chromosome reprogramming in the mouse inner cell mass.”

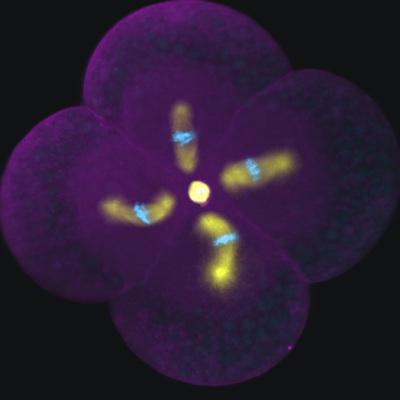

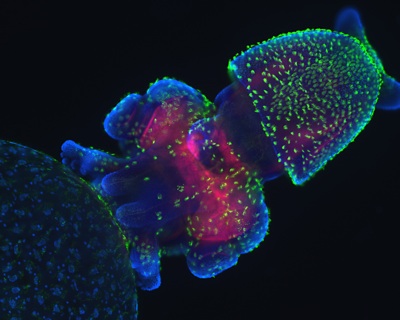

Mammalian dosage compensation occurs by silencing one X-chromosome in female cells, termed X-chromosome Inactivation (XCI). Balancing X-linked gene transcription is critical for female development, and in most cells, the absence of XCI is lethal. Interestingly, female mouse germ cells and inner cell masses (ICMs) appear to be an exception, capable of handling imbalances in X-linked gene dosage and exhibiting activation of both X-chromosomes. These uncommitted cells have the unique ability to reset the epigenetic profile of inactive X-chromosomes. As a graduate student, I was drawn to investigate the mechanism of X-chromosome reactivation because I wanted to understand how epigenetic reprogramming occurs naturally in the embryo.

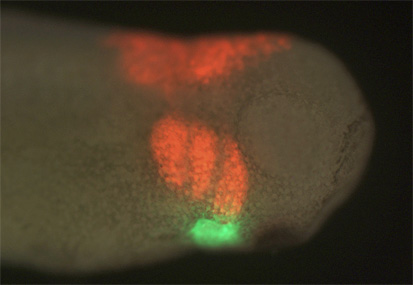

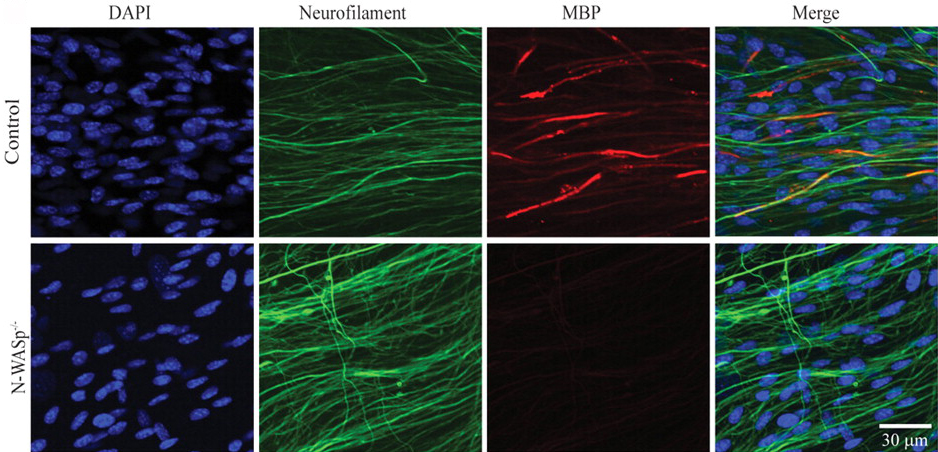

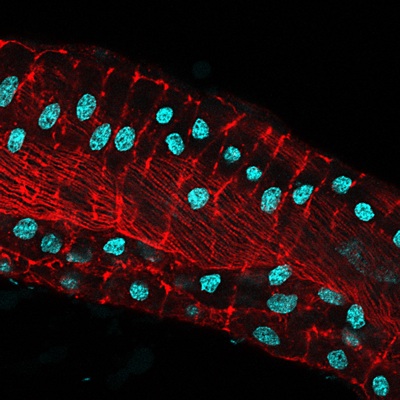

Most of what is known about the molecular events that initiate XCI has been extrapolated from observations of XCI in mouse cells. In the mouse embryo, the choice of which X-chromosome to be silenced is made stochastically; maternal and paternal X-chromosomes have an equal chance of being silenced and the end result is a random pattern of XCI. In contrast, extraembryonic tissues exhibit an imprinted form of XCI, and the paternal X-chromosome appears to be predetermined for silencing. It has been the prevailing opinion in the field that a master controller, the Xist non-coding RNA, regulates XCI. Xist RNA has been linked to almost every step in the XCI mechanism, including choice, initiation, and maintenance; however, its exact role is still unknown. What is clear is that Xist transcripts coat the X-chromosome in cis, recruiting epigenetic modifying proteins that are responsible for forming inactive-X heterochromatin.

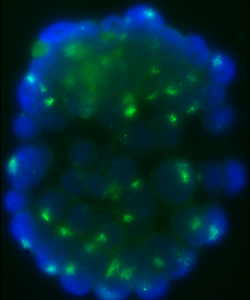

It had previously been shown that in all cells of the female preimplantation mouse embryo, Xist transcripts coat and recruit the repressive histone modification H3K27me3 to the Xp. However, X-linked gene expression at single cell resolution had not been directly analyzed, relative to cell fate in the embryo. In our manuscript, we definitively show that all cells, irrespective of lineage, establish imprinted XCI by the early blastocyst stage. This sets up a situation in the ICM; epiblast cells must undergo a reactivation/inactivation cycle. During ICM maturation, epiblast cells exhibit progressive upregulation of Nanog expression, coincident with their transition to ground-state pluripotency. Curiously, Xist is a target of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG. Based on the concept that Xist is the master regulator of XCI, it had been predicted that progressive upregulation of NANOG in the ICM leads to Xist repression, resulting in loss of Xist coating and triggering reactivation of Xi genes.

We used a knockout of Grb2 to upregulate Nanog expression in the ICM. As might be predicted, increased NANOG dosage led to Xist repression, indicated by loss of Xist coating. However, X-linked gene silencing is maintained in cells that lack Xist coating, perhaps suggesting that induced epigenetic reprogramming is incomplete in these cells. These provocative results point to other factors, in addition to Xist, that are needed initiate Xi gene silencing. Recent results from Kalantry et al. Nature 2009, Namekawa et al. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, and Okamoto et al. Nature 2011 support these conclusions and the need for the field to reconsider mechanisms regulating XCI.

(more…)

(17 votes)

(17 votes)

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)