March in preprints

Posted by the Node, on 8 April 2024

Welcome to our monthly trawl for developmental and stem cell biology (and related) preprints.

The preprints this month are hosted on bioRxiv and arXiv – use these links below to get to the section you want:

- Patterning & signalling

- Morphogenesis & mechanics

- Genes & genomes

- Stem cells, regeneration & disease modelling

- Plant development

- Evo-devo

Research practice and education

Developmental biology

| Patterning & signalling

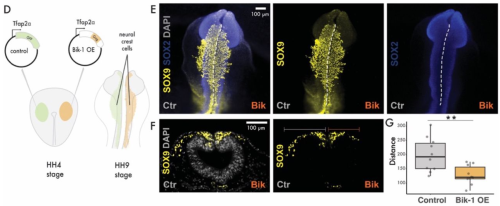

Shruti S. Tophkhane, Sarah J. Gignac, Katherine Fu, Esther M. Verheyen, Joy M. Richman

Na Qu, Abdelkader Daoud, Daniel O. Kechele, Jorge O. Múnera

Two opposing roles for Bmp signalling in the development of electrosensory lateral line organs

Alexander S. Campbell, Martin Minařík, Roman Franěk, Michaela Vazačová, Miloš Havelka, David Gela, Martin Pšenička, Clare V. H. Baker

Zhilin Deng, Wenqi Chang, Chengni Li, Botong Li, Shuying Huang, Jingtong Huang, Ke Zhang, Yuanyuan Li, Xingdong Liu, Qin Ran, Zhenhua Guo, Sizhou Huang

Symmetry breaking and fate divergence during lateral inhibition in Drosophila

Minh-Son Phan, Jang-mi Kim, Cara Picciotto, Lydie Couturier, Nisha Veits, Khallil Mazouni, François Schweisguth

Gyunghee G. Lee, Aidan J. Peterson, Myung-Jun Kim, Michael B. O’Connor, Jae H. Park

Dina Rekler, Shai Ofek, Sarah Kagan, Gilgi Friedlander, Chaya Kalcheim

A Foxf1-Wnt-Nr2f1 cascade promotes atrial cardiomyocyte differentiation in zebrafish

Ugo Coppola, Jennifer Kenney, Joshua S. Waxman

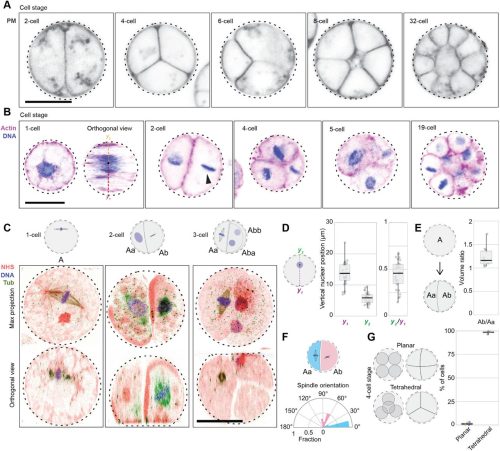

Vasileios R. Ouzounidis, Mattie Green, Charlotte de Ceuninck van Capelle, Clara Gebhardt, Helena Crellin, Cameron Finlayson, Bram Prevo, Dhanya K. Cheerambathur

Notch3 is a genetic modifier of NODAL signalling for patterning asymmetry during mouse heart looping

Tobias Holm Bønnelykke, Marie-Amandine Chabry, Emeline Perthame, Audrey Desgrange, Sigolène M. Meilhac

Miguel Angel Ortiz-Salazar, Elena Camacho-Aguilar, Aryeh Warmflash

| Morphogenesis & mechanics

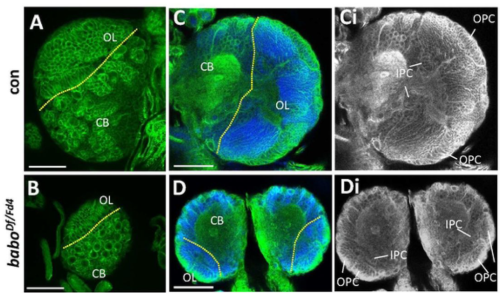

Cerebellar granule cell migration and folia development requires Mllt11/Af1q/Tcf7c

Marley Blommers, Danielle Stanton-Turcotte, Emily A. Witt, Mohsen Heidari, Angelo Iulianella

Roles of TYRO3 Family Receptors in Germ Cell Development During Mouse Testis Formation

Zhenhua Ming, Stefan Bagheri-Fam, Emily R Frost, Janelle M Ryan, Michele D Binder, Vincent R Harley

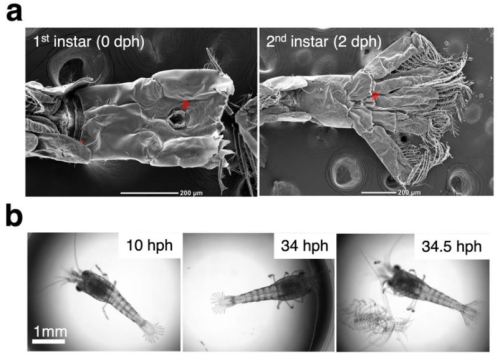

Post-embryonic tail development through molting of the freshwater shrimp Neocaridina denticulata

Haruhiko Adachi, Nobuko Moritoki, Tomoko Shindo, Kazuharu Arakawa

Hox-A2 protein expression in avian jaws cartilages and muscle primordia development

Stéphane Louryan, Myriam Duterre, Nathalie Vanmuylder

Estelle HIRSINGER, Cedrine BLAVET, Marie-Ange BONNIN, Lea BELLENGER, Tarek GHARSALLI, Delphine DUPREZ

Initiation and Formation of Stereocilia during the Development of Mouse Cochlear Hair Cells

Suraj Ranganath Chakravarthy, Thomas S. van Zanten, Raj K Ladher

Spns1-dependent endocardial lysosomal function drives valve morphogenesis through Notch1-signaling

Myra N. Chávez, Prateek Arora, Alexander Ernst, Marco Meer, Rodrigo A. Morales, Nadia Mercader

Development of Pial Collaterals by Extension of Pre-existing Artery Tips

Suraj Kumar, Niloufer Shanavas, Swarnadip Ghosh, Vinayak Sivaramakrishnan, Manish Dwari, Soumyashree Das

Kristen Kurtzeborn, Vladislav Iaroshenko, Tomáš Zárybnický, Julia Koivula, Heidi Anttonen, Darren Brigdewater, Ramaswamy Krishnan, Ping Chen, Satu Kuure

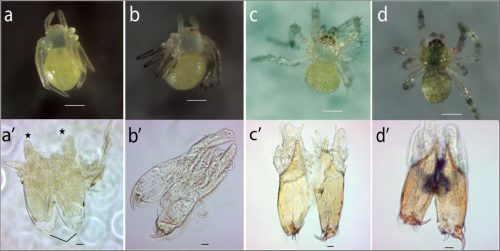

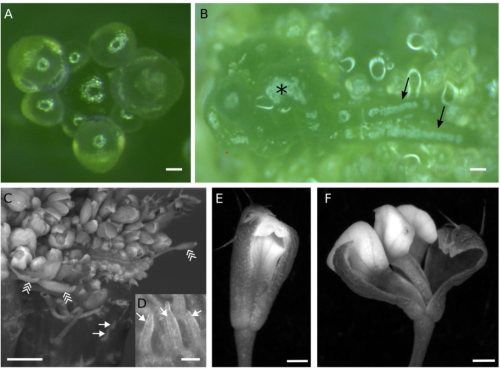

Venom gland organogenesis in the common house spider

Afrah Hassan, Grace Blakeley, Alistair P. McGregor, Giulia Zancolli

| Genes & genomes

José González-Martínez, Agustín Sánchez-Belmonte, Estefanía Ayala, Alejandro García, Enrique Nogueira, Jaime Muñoz, Anna Melati, Daniel Giménez, Ana Losada, Sagrario Ortega, Marcos Malumbres

Prabuddha Chakraborty, Terry Magnuson

Zhimin Xu, Zhao Wang, Lifang Wang, Yingchuan B. Qi

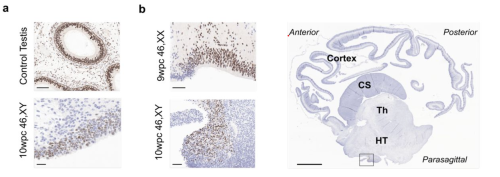

The transcriptomic landscape of monosomy X (45,X) during early human fetal and placental development

Jenifer P. Suntharalingham, Ignacio del Valle, Federica Buonocore, Sinead M. McGlacken-Byrne, Tony Brooks, Olumide K. Ogunbiyi, Danielle Liptrot, Nathan Dunton, Gaganjit K Madhan, Kate Metcalfe, Lydia Nel, Abigail R. Marshall, Miho Ishida, Neil J. Sebire, Gudrun E. Moore, Berta Crespo, Nita Solanky, Gerard S. Conway, John C. Achermann

Katherine L. Duval, Ashley R. Artis, Mary G. Goll

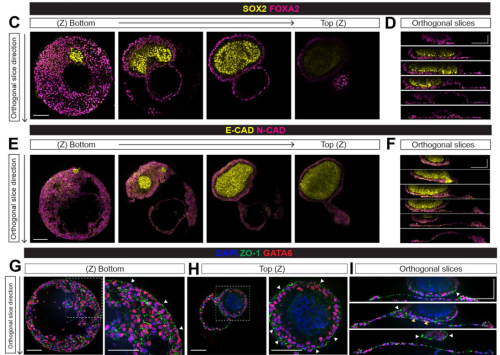

Temporally resolved early BMP-driven transcriptional cascade during human amnion specification

Nikola Sekulovski, Jenna C. Wettstein, Amber E. Carleton, Lauren N. Juga, Linnea E. Taniguchi, Xiaolong Ma, Sridhar Rao, Jenna K. Schmidt, Thaddeus G. Golos, Chien-Wei Lin, Kenichiro Taniguchi

Suchit Ahuja, Cynthia Adjekukor, Qing Li, Katrinka M. Kocha, Nicole Rosin, Elodie Labit, Sarthak Sinha, Ankita Narang, Quan Long, Jeff Biernaskie, Peng Huang, Sarah J. Childs

Screening of functional maternal-specific chromatin regulators in early embryonic development

Guifen Liu, Yiman Wang, Xiangxiu Wang, Wen Wang, Zheng Cao, Yong Zhang

Escape from X inactivation is directly modulated by levels of Xist non-coding RNA

Antonia Hauth, Jasper Panten, Emma Kneuss, Christel Picard, Nicolas Servant, Isabell Rall, Yuvia A. Pérez-Rico, Lena Clerquin, Nila Servaas, Laura Villacorta, Ferris Jung, Christy Luong, Howard Y. Chang, Judith B. Zaugg, Oliver Stegle, Duncan T. Odom, Agnese Loda, Edith Heard

What makes clocks tick? Characterizing developmental dynamics of adult epigenetic clock sites

Rosa H. Mulder, Alexander Neumann, Janine F. Felix, Matthew Suderman, Charlotte A. M. Cecil

Sex differences in early human fetal brain development

Federica Buonocore, Jenifer P Suntharalingham, Olumide K Ogunbiyi, Aragorn Jones, Nadjeda Moreno, Paola Niola, Tony Brooks, Nita Solanky, Mehul T. Dattani, Ignacio del Valle, John C. Achermann

Tim Casey-Clyde, S. John Liu, Juan Antonio Camara Serrano, Camilla Teng, Yoon-Gu Jang, Harish N. Vasudevan, Jeffrey O. Bush, David R. Raleigh

Yiqiao Zheng, Gary D. Stormo, Shiming Chen

Shruthi Bandyadka, Diane PV Lebo, Albert Mondragon, Sandy B Serizier, Julian Kwan, Jeanne S Peterson, Alexandra Y Chasse, Victoria Jenkins, Anoush Calikyan, Anthony Ortega, Joshua D Campbell, Andrew Emili, Kimberly McCall

Jay N. Joshi, Neha Changela, Lia Mahal, Tyler Defosse, Janet Jang, Lin-Ing Wang, Arunika Das, Joanatta G. Shapiro, Kim McKim

Shaonil Binti, Adison G. Linder, Philip T. Edeen, David S. Fay

Sofia E. Luna, Joab Camarena, Jessica P. Hampton, Kiran R. Majeti, Carsten T. Charlesworth, Eric Soupene, Sridhar Selvaraj, Kun Jia, Vivien A. Sheehan, M. Kyle Cromer, Matthew H. Porteus

Sulzyk Valeria, Curci Ludmila, Lucas N González, Rebagliati Cid Abril, Weigel Muñoz Mariana, Patricia S Cuasnicu

Suvimal Kumar Sindhu, Archita Mishra, Niveda Udaykumar, Jonaki Sen

BCL11b interacts with RNA and proteins involved in RNA processing and developmental diseases

Haitham Sobhy, Marco De Rovere, Amina Ait-Ammar, Muhammad Kashif, Clementine Wallet, Fadoua Daouad, Thomas Loustau, Carine Van Lint, Christian Schwartz, Olivier Rohr

Menghan Wang, Ana Di Pietro-Torres, Christian Feregrino, Maëva Luxey, Chloé Moreau, Sabrina Fischer, Antoine Fages, Patrick Tschopp

Barbara Zhao, Jacob Socha, Andrea Toth, Sharlene Fernandes, Helen Warheit-Niemi, Brandy Ruff, Gurgit K. Khurana Hershey, Kelli L. VanDussen, Daniel Swarr, William J. Zacharias

Hristo Todorov, Stephan Weißbach, Laura Schlichtholz, Hanna Mueller, Dewi Hartwich, Susanne Gerber, Jennifer Winter

| Stem cells, regeneration & disease modelling

Antonia Wiegering, Isabelle Anselme, Ludovica Brunetti, Laura Metayer-Derout, Damelys Calderon, Sophie Thomas, Stéphane Nedelec, Alexis Eschstruth, Sylvie Schneider-Maunoury, Aline Stedman

“Identification of microRNAs regulated by E2F transcription factors in human pluripotent stem cells”

María Soledad Rodríguez-Varela, Mercedes Florencia Vautier, Sofía Mucci, Luciana Isaja, Elmer Fernández, Gustavo Emilio Sevlever, María Elida Scassa, Leonardo Romorini

Fabrication of elastomeric stencils for patterned stem cell differentiation

Stefanie Lehr, Jack Merrin, Monika Kulig, Thomas Minchington, Anna Kicheva

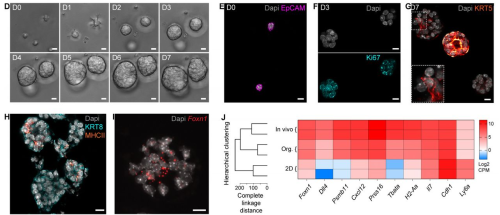

Self-organization of embryonic stem cells into a reproducible embryo model through epigenome editing

Gerrald A. Lodewijk, Sayaka Kozuki, Clara Han, Benjamin R. Topacio, Abolfazl Zargari, Seungho Lee, Gavin Knight, Randolph Ashton, Lei S. Qi, S. Ali Shariati

Transcription factor-based transdifferentiation of human embryonic to trophoblast stem cells

Paula A. Balestrini, Abdelbaki Ahmed, McCarthy Afshan, Liani Devito, Claire E. Senner, Alice E. Chen, Prabhakaran Munusamy, Paul Blakeley, Kay Elder, Phil Snell, Leila Christie, Paul Serhal, Rabi A. Odia, Mahesh Sangrithi, Kathy K. Niakan, Norah M.E. Fogarty

Noura Aldous, Ahmed K. Elsayed, Bushra Memon, Sadaf Ijaz, Sikander Hayat, Essam M. Abdelalim

Thymic epithelial organoids mediate T cell development

Tania Hübscher, L. Francisco Lorenzo-Martín, Thomas Barthlott, Lucie Tillard, Jakob J. Langer, Paul Rouse, C. Clare Blackburn, Georg Holländer, Matthias P. Lutolf

Zhiwei Feng, Bingrui Zhou, Qizhi Shuai, Yunliang Wei, Ning Jin, Xiaoling Wang, Hong Zhao, Zhizhen Liu, Jun Xu, Jianbing Mu, Jun Xie

Derivation of elephant induced pluripotent stem cells

Evan Appleton, Kyunghee Hong, Cristina Rodríguez-Caycedo, Yoshiaki Tanaka, Asaf Ashkenazy-Titelman, Ketaki Bhide, Cody Rasmussen-Ivey, Xochitl Ambriz-Peña, Nataly Korover, Hao Bai, Ana Quieroz, Jorgen Nelson, Grishma Rathod, Gregory Knox, Miles Morgan, Nandini Malviya, Kairui Zhang, Brody McNutt, James Kehler, Amanda Kowalczyk, Austin Bow, Bryan McLendon, Brandi Cantarel, Matt James, Christopher E. Mason, Charles Gray, Karl R. Koehler, Virginia Pearson, Ben Lamm, George Church, Eriona Hysolli

Her9 controls the stemness properties of the hindbrain boundary cells

Carolyn Engel-Pizcueta, Covadonga F Hevia, Adrià Voltes, Jean Livet, Cristina Pujades

Regenerative clustering of Enteroblasts in the Drosophila midgut revealed by a morphometric analysis

Fionna Zhu, Michael J. Murray

An Lgr5-independent developmental lineage is involved in mouse intestinal regeneration

Maryam Marefati, Valeria Fernandez-Vallone, Morgane Leprovots, Gabriella Vasile, Frédérick Libert, Anne Lefort, Gilles Dinsart, Achim Weber, Jasna Jetzer, Marie-Isabelle Garcia, Gilbert Vassart

Frédéric Rosa, Nicolas Dray, Laure Bally-Cuif

Rei Yagasaki, Ryo Nakamura, Yuuki Shikaya, Ryosuke Tadokoro, Ruolin Hao, Zhe Wang, Mototsugu Eiraku, Masafumi Inaba, Yoshiko Takahashi

Abdulvasey Mohammed, Benjamin D. Solomon, Priscila F. Slepicka, Kelsea M. Hubka, Hanh Dan Nguyen, Wenqing Wang, Martin Arreola, Michael G. Chavez, Christine Y. Yeh, Doo Kyung Kim, Virginia Winn, Casey A. Gifford, Veronika Kedlian, Jong-Eun Park, Georg A. Hollander, Vittorio Sebastiano, Purvesh Khatri, Sarah A. Teichmann, Andrew J. Gentles, Katja G. Weinacht

Tuft cells act as regenerative stem cells in the human intestine

Lulu Huang, Jochem H. Bernink, Amir Giladi, Daniel Krueger, Gijs J.F. van Son, Maarten H. Geurts, Georg Busslinger, Lin Lin, Maurice Zandvliet, Peter J. Peters, Carmen Lopez-Iglesias, Christianne J. Buskens, Willem A. Bemelman, Harry Begthel, Hans Clevers

Developmental Regulation of Alternative Polyadenylation in an Adult Stem Cell Lineage

Lorenzo Gallicchio, Neuza Reis Matias, Fabian Morales-Polanco, Iliana Nava, Sarah Stern, Yi Zeng, Margaret Theresa Fuller

Human spermatogonial stem cells retain states with a foetal-like signature

Stephen J Bush, Rafail Nikola, Seungmin Han, Shinnosuke Suzuki, Shosei Yoshida, Benjamin D Simons, Anne Goriely

Interplay of IGF1R and estrogen signaling regulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells

Ying Xie, Dongxi Xiang, Xin Hu, Hubert Pakula, Eun-Sil Park, Jiadong Chi, Douglas E. Linn, Luwei Tao, Zhe Li

Senolytic CAR T cells reverse aging-associated defects in intestinal regeneration and fitness

Onur Eskiocak, Saria Chowdhury, Vyom Shah, Emmanuella Nnuji-John, Charlie Chung, Jacob A. Boyer, Alexander S. Harris, Jill Habel, Michel Sadelain, Semir Beyaz, Corina Amor

Nuwanthika Wathuliyadde, Katherine E. Willmore, Gregory M. Kelly

Extracellular vesicles promote proliferation in an animal model of regeneration

Priscilla N. Avalos, Lily L. Wong, David J. Forsthoefel

Extended culture of 2D gastruloids to model human mesoderm development

Bohan Chen, Hina Khan, Zhiyuan Yu, LiAng Yao, Emily Freeburne, Kyoung Jo, Craig Johnson, Idse Heemskerk

Sze Hang Kwok, Yuejiang Liu, David Bilder, Jung Kim

Fibroblasts enhance the growth and survival of adult feline small intestinal organoids

Nicole D Hryckowian, Katelyn Studener, Laura J Knoll

Capture of Human Neuromesodermal and Posterior Neural Tube Axial Stem Cells

Dolunay Kelle, Enes Ugur, Ejona Rusha, Dmitry Shaposhnikov, Alessandra Livigni, Sandra Horschitz, Mahnaz Davoudi, Andreas Blutke, Judith Bushe, Michael Sterr, Ksenia Arkhipova, Benjamin Tak, Ruben de Vries, Mazène Hochane, Britte Spruijt, Aicha Haji Ali, Heiko Lickert, Annette Feuchtinger, Philipp Koch, Matthias Mann, Heinrich Leonhardt, Valerie Wilson, Micha Drukker

Marija Lazovska, Kristine Salmina, Dace Pjanova, Bogdan I. Gerashchenko, Jekaterina Erenpreisa

Augusto Ortega Granillo, Daniel Zamora, Robert R. Schnittker, Allison R. Scott, Jonathon Russell, Carolyn E. Brewster, Eric J. Ross, Daniel A. Acheampong, Kevin Ferro, Jason A. Morrison, Boris Y. Rubinstein, Anoja G. Perera, Wei Wang, Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado

Lucia Leitner, Martina Schultheis, Franziska Hofstetter, Claudia Rudolf, Valeria Kizner, Kerstin Fiedler, Marie-Therese Konrad, Julia Höbaus, Marco Genini, Julia Kober, Elisabeth Ableitner, Teresa Gmaschitz, Diana Walder, Georg Weitzer

Melody Autumn, Yinan Hu, Jenny Zeng, Sarah K. McMenamin

| Plant development

Qian Ma, Sijia Liu, Sara Raggi, Siamsa M. Doyle, Barbora Pařízková, Deepak Kumar Barange, Edward G. Wilkinson, Isidro Crespo Garcia, Joakim Bygdell, Gunnar Wingsle, Dirk Roeland Boer, Lucia C. Strader, Fredrik Almqvist, Ondřej Novák, Stéphanie Robert

Eleanore J. Ritter, Carolyn D. K. Graham, Chad Niederhuth, Marjorie Gail Weber

Xiaosa Xu, Michael Passalacqua, Brian Rice, Edgar Demesa-Arevalo, Mikiko Kojima, Yumiko Takebayashi, Benjamin Harris, Hitoshi Sakakibara, Andrea Gallavotti, Jesse Gillis, David Jackson

Léa Rambaud-Lavigne, Aritra Chatterjee, Simone Bovio, Virginie Battu, Quentin Lavigne, Namrata Gundiah, Arezki Boudaoud, Pradeep Das

Postembryonic developmental roles of the Arabidopsis KEULE gene

Alejandro Ruiz-Bayón, Carolina Cara-Rodríguez, Raquel Sarmiento-Mañús, Rafael Muñoz-Viana, Francisca M. Lozano, María Rosa Ponce, José Luis Micol

Gerardo del Toro-de León, Joram van Boven, Juan Santos-González, Wen-Biao Jiao, Korbinian Schneeberger, Claudia Köhler

An atlas of Brachypodium distachyon lateral root development

Cristovao De Jesus Vieira Teixeira, Kevin Bellande, Alja van der Schuren, Devin O’Connor, Christian S. Hardtke, Joop EM Vermeer

Uria Ramon, Amit Adiri, Hadar Cheriker, Ido Nir, Yogev Burko, David Weiss

Chiara A. Airoldi, Chao Chen, Humberto Herrera-Ubaldo, Hongbo Fu, Carlos A. Lugo, Alfred J. Crosby, Beverley J. Glover

A RALF-Brassinosteroid morpho-signaling circuit regulates Arabidopsis hypocotyl cell shape

David Biermann, Michelle von Arx, Kaltra Xhelilaj, David Séré, Martin Stegmann, Sebastian Wolf, Cyril Zipfel, Julien Gronnier

| Evo-devo

Rewinding the developmental tape shows how bears break a developmental rule

Otto E. Stenberg, Jacqueline E. Moustakas-Verho, Jukka Jernvall

Avery Leigh Russell, Rosana Zenil-Ferguson, Stephen L. Buchmann, Diana D. Jolles, Ricardo Kriebel, Mario Vallejo-Marín

Comparative analysis of Wolbachia maternal transmission and localization in host ovaries

Michael T.J. Hague, Timothy B. Wheeler, Brandon S. Cooper

Paula R. Roy, Dean M. Castillo

A male-essential microRNA is key for avian sex chromosome dosage compensation

Amir Fallahshahroudi, Leticia Rodríguez-Montes, Sara Yousefi Taemeh, Nils Trost, Memo Tellez Jr., Maeve Ballantyne, Alewo Idoko-Akoh, Lorna Taylor, Adrian Sherman, Enrico Sorato, Martin Johnsson, Margarida Cardoso Moreira, Mike J. McGrew, Henrik Kaessmann

Repatterning of mammalian backbone regionalization in cetaceans

Amandine Gillet, Katrina E. Jones, Stephanie E. Pierce

A multicellular developmental program in a close animal relative

Marine Olivetta, Chandni Bhickta, Nicolas Chiaruttini, John Burns, Omaya Dudin

Gene regulatory network co-option is sufficient to induce a morphological novelty in Drosophila

Gavin Rice, Tatiana Gaitan-Escudero, Kenechukwu Charles-Obi, Julia Zeitlinger, Mark Rebeiz

Aurélie Hintermann, Christopher Chase Bolt, M. Brent Hawkins, Guillaume Valentin, Lucille Lopez-Delisle, Sandra Gitto, Paula Barrera Gómez, Bénédicte Mascrez, Thomas A. Mansour, Tetsuya Nakamura, Matthew P. Harris, Neil H. Shubin, Denis Duboule

Independent size regulation of bones and appendages in zebrafish

Toshihiro Aramaki, Shigeru Kondo

Cell Biology

Neutral evolution of snoRNA Host Gene long non-coding RNA affects cell fate control

Matteo Vietri Rudan, Kalle H. Sipilä, Christina Philippeos, Clarisse Gânier, Victor A. Negri, Fiona M. Watt

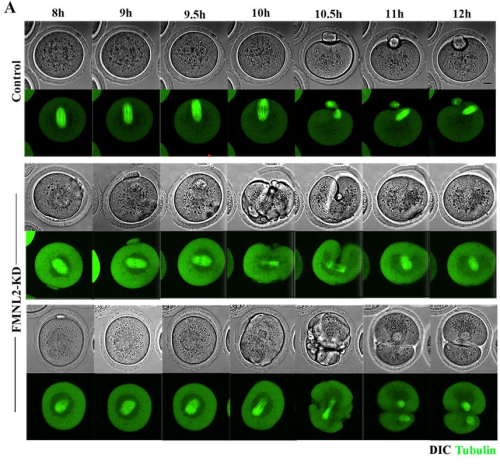

FMNL2 regulates actin for ER and mitochondria distribution in oocyte meiosis

Meng-Hao Pan, Zhen-Nan Pan, Ming-Hong Sun, Xiao-Han Li, Jia-Qian Ju, Shi-Ming Luo, Xiang-Hong Ou, Shao-Chen Sun

Aurora B controls microtubule stability to regulate abscission dynamics in stem cells

Snježana Kodba, Amber Öztop, Eri van Berkum, Malina K. Iwanski, Wilco Nijenhuis, Lukas C. Kapitein, Agathe Chaigne

Mitochondrial dynamics regulate cell size in the developing cochlea

James D. B. O’Sullivan, Stephen Terry, Claire A. Scott, Anwen Bullen, Daniel J. Jagger, Zoë F. Mann

Cell extrusion – a novel mechanism driving neural crest cell delamination

Emma Moore, Ruonan Zhao, Mary C McKinney, Kexi Yi, Christopher Wood, Paul Trainor

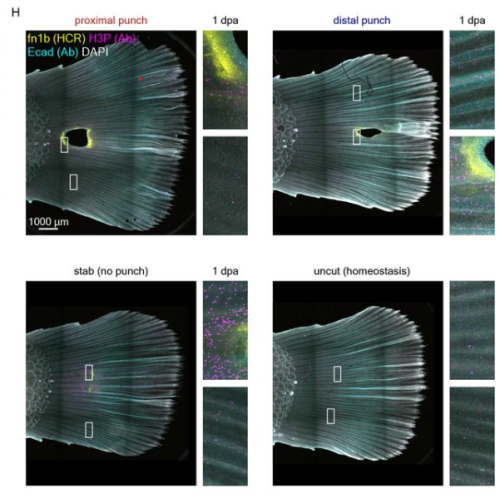

Florian Constanty, Bailin Wu, Ke-Hsuan Wei, I-Ting Lin, Julia Dallmann, Stefan Guenther, Till Lautenschlaeger, Rashmi Priya, Shih-Lei Lai, Didier Y.R. Stainier, Arica Beisaw

Yi-Ting Huang, Lauren L. Hesting, Brian R. Calvi

Steven L. Brody, Jiehong Pan, Tao Huang, Jian Xu, Huihui Xu, Jeffrey Koenitizer, Steven K. Brennan, Rashmi Nanjundappa, Thomas G. Saba, Andrew Berical, Finn J. Hawkins, Xiangli Wang, Rui Zhang, Moe R. Mahjoub, Amjad Horani, Susan K. Dutcher

Pooja Popli, Arin K. Oestreich, Vineet K. Maurya, Marina N. Rowen, Ramya Masand, Michael J. Holtzman, Yong Zhang, John Lydon, Shizuo Akira, Kelle H. Moley, Ramakrishna Kommagani

Defining the contribution of Troy-positive progenitor cells to the mouse esophageal epithelium

David Grommisch, Menghan Wang, Evelien Eenjes, Maja Svetličič, Qiaolin Deng, Pontus Giselsson, Maria Genander

Shruthi Bandyadka, Diane PV Lebo, Albert Mondragon, Sandy B Serizier, Julian Kwan, Jeanne S Peterson, Alexandra Y Chasse, Victoria Jenkins, Anoush Calikyan, Anthony Ortega, Joshua D Campbell, Andrew Emili, Kimberly McCall

Gag proteins encoded by endogenous retroviruses are required for zebrafish development

Ni-Chen Chang, Jonathan N. Wells, Andrew Y. Wang, Phillip Schofield, Yi-Chia Huang, Vinh H. Truong, Marcos Simoes-Costa, Cédric Feschotte

FilamentID reveals the composition and function of metabolic enzyme polymers during gametogenesis

Jannik Hugener, Jingwei Xu, Rahel Wettstein, Lydia Ioannidi, Daniel Velikov, Florian Wollweber, Adrian Henggeler, Joao Matos, Martin Pilhofer

Desynchronization between timers provokes transient arrest during C. elegans development

Francisco J. Romero-Expósito, Almudena Moreno-Rivero, Marta Muñoz-Barrera, Sabas García-Sánchez, Fernando Rodríguez-Peris, Nicola Gritti, Francesca Sartor, Martha Merrow, Jeroen S. van Zon, Alejandro Mata-Cabana, María Olmedo

Modelling

Manica Balant, Teresa Garnatje, Daniel Vitales, Oriane Hidalgo, Daniel H. Chitwood

Yusuke Sakai, Jun Hakura

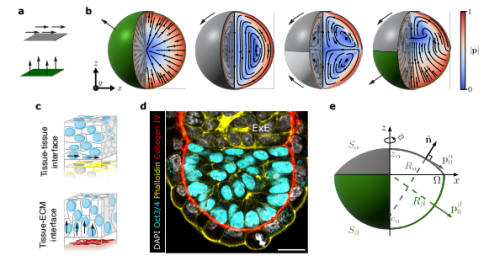

Pamela C. Guruciaga, Takafumi Ichikawa, Takashi Hiiragi, Anna Erzberger

Mechanochemical bistability of intestinal organoids enables robust morphogenesis

Shi-Lei Xue, Qiutan Yang, Prisca Liberali, Edouard Hannezo

Waves, patterns and bifurcations: a tutorial review on the vertebrate segmentation clock

Paul François, Victoria Mochulska

Michael A. Ramirez-Sierra, Thomas R. Sokolowski

Tools & Resources

Deep learning methods to forecasting human embryo development in time-lapse videos

Akriti Sharma, Alexandru Dorobantiu, Saquib Ali, Mario Iliceto, Mette H. Stensen, Erwan Delbarre, Michael A. Riegler, Hugo L. Hammer

Comprehensive mapping of sensory and sympathetic innervation of the developing kidney

Pierre-Emmanuel Y. N’Guetta, Sarah R. McLarnon, Adrien Tassou, Matan Geron, Sepenta Shirvan, Rose Z. Hill, Grégory Scherrer, Lori L. O’Brien

EyeHex toolbox for complete segmentation of ommatidia in fruit fly eyes

Huy Tran, Nathalie Dostatni, Ariane Ramaekers

Spatial Dynamics of the Developing Human Heart

Enikő Lázár, Raphaël Mauron, Žaneta Andrusivová, Julia Foyer, Ludvig Larsson, Nick Shakari, Sergio Marco Salas, Sanem Sariyar, Jan N. Hansen, Marco Vicari, Paulo Czarnewski, Emelie Braun, Xiaofei Li, Olaf Bergmann, Christer Sylvén, Emma Lundberg, Sten Linnarsson, Mats Nilsson, Erik Sundström, Igor Adameyko, Joakim Lundeberg

Transcriptional dynamics of the murine heart during perinatal development at single-cell resolution

Lara Feulner, Florian Wünnemann, Jenna Liang, Philipp Hofmann, Marc-Phillip Hitz, Denis Schapiro, Severine Leclerc, Patrick Piet van Vliet, Gregor Andelfinger

Xianfeng Yang, Qiufei Lin, Jinu Udayabhanu, Yuwei Hua, Xuemei Dai, Shichao Xin, Huasun Huang, Tiandai Huang

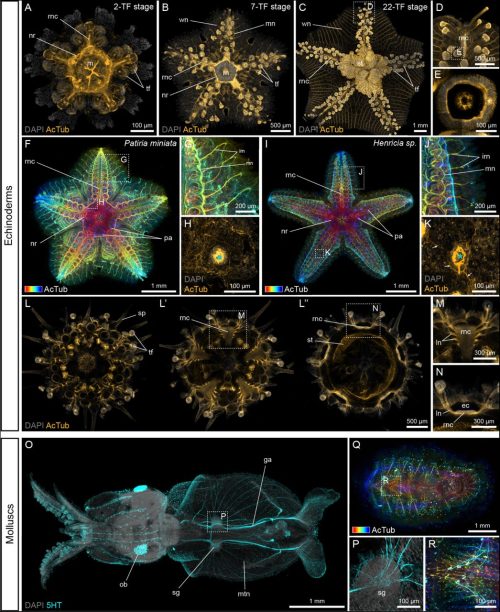

D. Nathaniel Clarke, Laurent Formery, Christopher J Lowe

Ke Zhang, Yanqiu Wang, Qi An, Hengjing Ji, Defu Wu, Xuri Li, Xuran Dong, Chun Zhang

Highly efficient tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombination in embryonic, larval and adult zebrafish

Edita Bakūnaitė, Emilija Gečaitė, Justas Lazutka, Darius Balciunas

Camilo V. Echeverria Jr., Tess A. Leathers, Crystal D. Rogers

Elliot W. Jackson, Emilio Romero, Svenja Kling, Yoon Lee, Evan Tjeerdema, Amro Hamdoun

A high-throughput method for quantifying Drosophila fecundity

Andreana Gomez, Sergio Gonzalez, Ashwini Oke, Jiayu Luo, Johnny B. Duong, Raymond M. Esquerra, Thomas Zimmerman, Sara Capponi, Jennifer C. Fung, Todd G. Nystul

Research practice & education

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in Drosophila via visual selection in a summer classroom

Lutz Kockel, Valentina Zhang, Jenna Wang, Clara Gulick, Madeleine E. Laws, Arjun Rajan, Nicole Lantz, Ayla Asgarova, Lillian Dai, Kristian Garcia, Charlene Kim, Michelle Li, Patricio Ordonez-Acosta, Dongshen Peng, Henry Shull, Lauren Tse, Yixang Wang, Wenxin Yu, Zee Zhou, Anne Rankin, Sangbin Park, Seung K. Kim

Australian researchers’ perceptions and experiences with stem cell registration

Mengqi Hu, Dan Santos, Edilene Lopes, Dianne Nicol, Andreas Kurtz, Nancy Mah, Sabine C. Muller, Rachel A. Ankeny, Christine A. Wells

Katy Andrews, Rosalie Stoneley, Katja Eckl

Rendering protein structures inside cells at the atomic level with Unreal Engine

Muyuan Chen

Perry G. Beasley-Hall, Pam Papadelos, Anne Hewitt, Charlotte R. Lassaline, Kate D. L. Umbers, Michelle T. Guzik

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)

(1 votes)

(1 votes)